The total experience

Tom Sutcliffe goes to Wexford and finds Guinness and convivial company plus three operas nly in Ireland, surely, would a suc- cessful opera festival be based on reviving operatic failures. But putting it baldly like that doesn't explain the attraction of the Wexford recipe. One advantage of failure, of course, is that it's a commodity in virtu- ally unlimited supply. (Or so I said, when a senior Guinness executive was wondering if the Wexford product could ever run out.) Another is that, since nowadays Wexford's operas are almost all profoundly obscure, punters can't and don't discriminate between them — until they've actually heard them, when all are eager to put their view on the rival merits (it does seem per- verse, though, to eschew the use of sur- titles). In reality, Wexford, like Glyndebourne, is a package in which actual opera is a comparatively minor factor. The total experience is what people buy: friend- ly company, sales of bad paintings on every wall, nice concerts on the side, fresh vocal talent, variable but sometimes superb cook- ing in restaurants around the county, Guin- ness, Jamieson's, conviviality. If an opera proves worthwhile — that is sheer bonus.

Wexford wasn't always so studiedly aca- demic in its repertoire. In 1964 they did Lucia and Count ay, in 1965 Don Qui- chotte and Traviata. My first visit in 1972 included Katya, Wexford's only Janacek so far, and a memorably dismal Oberon. Gluck's Orfeo was on the menu in 1977, but after the 1982 arrival of Elaine Padmore as artistic director you didn't expect to find standard rep. And now Luigi Ferrari, the current artistic director who also runs the Rossini festival at Pesaro, has really pushed the boat out. The attractions this year (my 17th visit) were Carlos Gomes, Pavel Haas and Riccardo Zandonai.

Gomes's Fosca of 1873 is a wildly absurd tale of romance, piratical extortion and human traffic almost on the scale of Ponchielli's Gioconda. But Giovanni Agostinucci's staging (he also designed) kept the lighting low, revolved a pair of edging flats from shiny rocky surface to neo-classical ruin, and started most scenes with stentorian declamation half way up a narrowing centre-stage flight of steps. Fosca was probably the opera most visitors (but not critics) liked best. Sheer stand and deliver, and Elmira Veda's Fosca and Tigran Martirossian as her brother the pirate leader Gajolo (a glowing golden bass) did exactly that in spades. Veda has a full-throatedly violent rich soprano with a serious bottom register that you just know is going to the bad. Sure enough, at the end she takes poison, having failed to capture Paolo the man she fancies (a slightly underwhelming American tenor Fernando del Valle) while being really rather decent to Paolo's beloved Delia. Anatoly Lochak as the treacherous baritone Cambro is also impressive. But it's the way Veda's Fosca copes with Gomes's exaggerated vocal gymnastics that really gets things going.

Wexford programme articles often claim composers as 'missing links'. Gomes's Fosca includes many pre-echoes of musical ideas more effectively reworked by Verdi in Boccanegra, Otello and Falstaff But Gomes, with heavily predictable accompa- niments, clumsy dramatic structure and feeble characterisation, is a pretty bad composer — his main technique evidently being to flesh out climactic opportunities in the vocal lines.

The other two Wexford composers, Zan- donai and Haas with their between-the- wars works, are infinitely more sophisticated and interesting — though all three operas this year end with the inconse- quential deaths of central characters about whom we care little. Zandonai's I Cavalieri di Ekebu is a highly individual and intense mixture of Tristan and versimo which I found constantly stimulating. The staging by Gabriele Vacis uses models of scenes in suspended glass cases to evoke the real nat- uralistic setting, while what we actually see on stage follows a fairly formalised scheme. Vocal values predominate, and little attempt is made to interpret the diabolic features of the story about a do-gooding female 'Commandante' responding to the Big Issue by providing lives and work for destitute men with a forge. Dario Volonte as the hero, a defrocked priest Giosta Berling who has sold himself to the devil, sings out superbly — though upstaged slightly by the 20-year-old subtle Maltese tenor Joseph Calleja as Liecrona (certainly one to watch out for). Maxim Milchailov as the devilish Sintram, father of Giosta's beloved Anna, cackles and gives throat magnificently. And Francesca Franci is stylish and touching as the Commandante in smart breeches and boots. The final scene when the forge is restored to opera- tion and the spell is lifted, with plenty of choral paeans, is thrilling in every way.

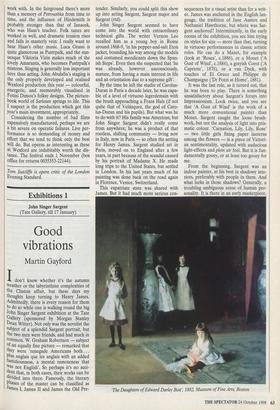

Haas's Sarlatan (Charlatan, given its pre- mière in 1938) is an incredibly promising and accomplished first and last opera by a Czech composer who died in Auschwitz in 1944 after almost three years in Theresien- stadt. It's about the life of a romanticising fairground quack, Dr Pustrpalk, and its plot is strikingly and quirkily painted. But one never quite gathers what one is sup- posed to make of this fable, since the good doctor is a failure at his profession and a fake. The bold characterisations are not palpably alive. The conductor Israel Yinon has some consistently inventive material to work with. In the fairground there's more than a memory of Petroushka from time to time, and the influence of Hindemith is probably stronger than that of Janacek, who was Haas's teacher. Folk tunes are worked in well, and dramatic tension rises and falls in masterly vein: I really want to hear Haas's other music. Luca Grassi is quite glamorous as Pustrpalk, and the stat- uesque Viktoria Vizin makes much of the lovely Amaranta, who becomes Pustrpalk's mistress. Singing is generally less important here than acting. John Abulafia's staging is the only properly developed and realised Wexford production this year — colourful, energetic, and memorably visualised in Fotini Dimou's folksy designs. The picture- book world of Sarlatan springs to life. This I suspect is the production which got this Year's main investment, appropriately.

Considering the number of bad films expensively manufactured, perhaps we are a bit severe on operatic failures. Live per- formance is so demanding of money and effort that we tend to think only the best Will do. But operas as interesting as these at Wexford are indubitably worth the dis- tance. The festival ends 1 November (box office for returns 0035353-22144).

Tom Sutcliffe is opera critic of the London Evening Standard.

Previous page

Previous page