Exhibitions 1

John Singer Sargent (Tate Gallery, till 17 January)

Good vibrations

Martin Gayford

Idon't know whether it's the autumn Weather or the labyrinthine complexities of the Clinton affair, but these days my thoughts keep turning to Henry James. Admittedly, there is every reason for them to do so while one is walking round the big John Singer Sargent exhibition at the Tate Gallery (sponsored by Morgan Stanley Dean Witter). Not only was the novelist the subject of a splendid Sargent portrait, but the two men were friends, and had much in Common. W. Graham Robertson — subject of an equally fine picture — remarked that they were 'renegade Americans both ... Plus anglais que les anglais with an added fastidiousness, a mental remoteness that was not English'. So perhaps it's no acci- dent that, in both cases, their works can be divided into three. Famously, the literary Phases of the master can be classified as James I, James II and James the Old Pre- tender. Similarly, you could split this show up into acting Sargent, Sargent major and Sargent (rtd).

John Singer Sargent seemed to have come into the world with extraordinary technical gifts. The writer Vernon Lee recalled him as a young boy in Rome around 1868-9, 'in his pepper-and-salt Eton jacket, bounding his way among the models and costumed mendicants down the Span- ish Steps'. Even then she suspected that 'he was already, however unconsciously, mature, from having a main interest in life and an orientation due to a supreme gift'.

By the time he left the studio of Carolus- Duran in Paris a decade later, he was capa- ble of a level of virtuoso legerdemain with the brush approaching a Frans Hals (if not quite that of Velazquez, the god of Caro- lus-Duran and his pupils). But what was he to do with it? His family was American, but John Singer Sargent didn't really come from anywhere; he was a product of that rootless, shifting community — living now in Italy, now in Paris — so often the setting for Henry James. Sargent studied art in Paris, moved on to England after a few years, in part because of the scandal caused by his portrait of Madame X. He made long trips to the United States, but settled in London. In his last years much of his painting was done back on the road again in Florence, Venice, Switzerland.

This expatriate state was shared with James. But it had much more serious con- sequences for a visual artist than for a writ- er. James was anchored in the English lan- guage, the tradition of Jane Austen and Nathaniel Hawthorne, but where was Sar- gent anchored? Intermittently, in the early rooms of the exhibition, you see him trying on styles for size — more than that, turning in virtuoso performances in classic artistic roles. He can do a Manet, for example (look at 'Roses', c.1886), or a Monet CA Gust of Wind', c.1884), a greyish Corot CA Capriote', 1878), or a van Dyck, with touches of El Greco and Philippe de Champaigne (Dr Pozzi at Home', 1881).

It was the last role, as it turned out, that he was born to play. There is something unsatisfactory about Sargent's forays into Impressionism. Look twice, and you see that 'A Gust of Wind' is the work of a much more conventional painter than Monet. Sargent caught the loose brush- work, but not the analysis of light into pris- matic colour. 'Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose' — two little girls fixing paper lanterns among the flowers — is a piece of Victori- an sentimentality, updated with audacious light-effects and plein air feel. But it is fun- damentally gooey, or at least too gooey for me.

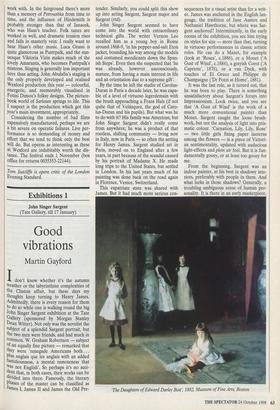

From the beginning, Sargent was an indoor painter, at his best in shadowy inte- riors, preferably with people in them. And what lurks in those shadows? Generally, a troubling ambiguous sense of human per- sonality. It is there in an early masterpiece, The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit', 1882, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston 'The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit' (1882), in which four little girls are dotted about a large, dark room. Huge Chinese vases loom above them. They stare out, each isolated from the rest. Something seems to have gone wrong (and, according to the catalogue, it probably had; two of those little girls became mentally unstable in later life).

This is Sargent at his best, and, on the evidence of this show, his finest work occurs when he encountered sitters who set off some interesting vibration. Among them, John Singer Sargent himself was not numbered, to judge from his inert self-por- trait. Much of the time he simply gave a magnificent performance as a grand old master portrait painter (acting Sargent). Looking at the 'Misses Vicker' (1884), one would scarcely guess the distaste Sargent apparently felt about the task of painting them CI am to paint three ugly women at Sheffield, dingy hole'). It is a very effective work in the van Dyck-Reynolds-Gainsbor- ough mode. The sitters look rich, docile, well-groomed and not ugly at all. But it scarcely lives in the mind.

The paintings that do, the truly major Sargent, go beyond the impression of sheen and opulence which he could conjure up so well. There is a hint, faint perhaps, but pre- sent, that something different, deeper is moving below the social gloss. In Lady Agnew's eyes, for example, there is, what? — weariness? irritation? sullen resent- ment? — whatever it is, it makes the pic- ture. The superb Lord Ribbesdale is satanically gentlemanly (`Ce grand diable de milord anglais' as the French public muttered when the painting was hung in Paris). Lord Dalhousie, lounging against a pillar in van Dyckian fashion, is weedily supercilious. From the Sitwell family group, the young Edith stares out with a challenging, girl-power look. Famously, 'Madame X' — a painting which looks to have suffered grievously from over-clean- ing — is elegant but depraved.

In all these cases, it is not Sargent's impersonation of the grand manner that makes the picture; it is the discrepancy between the way the subjects are presented and what Sargent leads you to suspect about their real, unglossy selves. When he does this, Sargent is a truly great portrait painter. But he did it only some of the time, and by and by he got bored with doing it all. In 1907, at the age of 51, he effectively retired as a portrait painter (the few he pro- duced in the remaining two decades of his life were mainly of friends, such as James, or the result of arm-twisting).

Instead he painted landscapes — skilful, but travel-poster deep — and continued with the murals in Boston, which, to judge from the sketches on show, are in a thor- oughly dated, pompous Parisian style utter- ly at variance with his best work. 'Gassed' is a response to the first world war both muted and stagy. This was Sargent (rtd). Why did he do it? We know very little about his private life; perhaps there wasn't much to know. His sexual interests are a mystery, but it is clear that he took great pleasure in food and drink (he complained he could not get enough to eat at the Chelsea Arts Club). It may be that he had a weak sense of self (those stylistic oscillations might imply as much), and an indolent nature. Several of his better late works deal with the subject of repose and siesta. Could it be that, after a few decades of brilliance, he reverted to type, and, like his expatriate parents, pre- ferred just to drift around looking at agree- able bits of the Grand Canal and the Boboli Gardens?

For advance bookin telephone First Call on 0171-420 0055.

Previous page

Previous page