BLACK DEEDS, BLACK HEROES

Richard Stengel explains why being accused of

terrible crimes can be a positive social asset among America's coloured population

New York AMONG the macabre jokes that made the rounds after the arrest of O.J. Simpson for the murder of his wife and a male friend — was the following: 'The bad news is that O.J. is going to prison; the good news is that Michael Jackson is taking the kids.'

It is not notably clever, but I mention it because O.J. Simpson and Michael Jack- son have something in common apart from sharing the punch line of a lame witticism. They are both famous black Americans who have become political heroes — mar- tyrs is perhaps the better word — in the black community after being accused of a crime.

Simpson and Jackson are not even the best examples of this phenomenon: witness former heavyweight boxing champion Mike Tyson, convicted of rape; Joe Jett of Kidder, Peabody, the stockbroker accused of a $350-million fraud, and, most recently, former Washington DC mayor Marion Barry who, after serving two years in prison for buying crack-cocaine in a hotel room, has convincingly won the nomina- tion for mayor in that overwhelmingly black city. Each of these men is seen by a large percentage of American blacks as having somehow been 'set up' by the white racist establishment. I. heard an articulate Los Angeles black woman say on a local television interview show, 'Well, when they saw how easy it was to take down Michael Jackson, O.J. wasn't far behind.' Dozens of polls taken in the last few months show that as many as 60 per cent of black Americans believe O.J. Simpson was framed, while only 10-15 per cent of whites think so. O.J.'s imprisonment has been accompanied by the kind of commer- cial popularisation in the black community once reserved for Nelson Mandela: 'Free O.J.' T-shirts, mugs, and hats are being sold on street corners while banners in front of his Tudor-style Los Angeles man- sion proclaim 'Turn The Juice Loose'. Simpson's attorney installed a free-call telephone number for citizens who might have information or evidence that could help 0.J.'s case: the line received 250,000 calls in its first week.

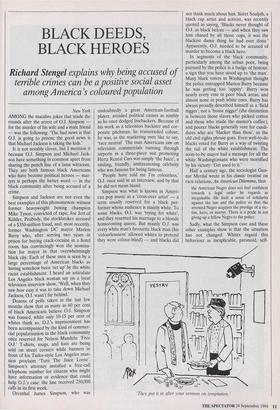

Orenthal James Simpson, who was undoubtedly a great American-football player, avoided political causes as nimbly as he once dodged linebackers. Because of his work as a television huckster and cor- porate pitchman, he transcended colour; he was, as the marketing men like to say, `race neutral'. The man Americans saw on television commercials running through airports in a three-piece suit promoting Hertz Rental Cars was simply 'the Juice', a smiling, friendly, unthreatening celebrity who was famous for being famous.

`People have told me I'm colourless,' O.J. once said in an interview, and by that he did not mean bland.

Simpson was what is known in Ameri- can pop music as a 'cross-over artist' — a term usually reserved for a black per- former whose audience is mainly white. To some blacks, O.J. was 'trying for white', and they resented his marriage to a blonde homecoming queen. But mainly O.J. was every white man's favourite black man (his `colourlessness' allowed whites to pretend they were colour-blind) — and blacks did 'They put it in after your sermon on temptation.' not think much about him. Sister Souljah, a black rap artist and activist, was recently quoted as saying, 'Blacks never thought of O.J. as black before — and when they saw him chased by all those cops, it was the blackest damn thing he had ever done.' Apparently, O.J. needed to be accused of murder to become a black hero.

In segments of the black community, particularly among the urban poor, being pursued by the police is a badge of honour, a sign that you have stood up to 'the man'. Many black voters in Washington thought the police entrapped Marion Barry because he was getting too 'uppity'. Barry won nearly every vote in poor black areas, and almost none in posh white ones. Barry has always proudly described himself as a 'field nigger', not a 'house nigger' (the distinction is between those slaves who picked cotton and those who made the master's coffee), and poorer blacks generally vote for candi- dates who are 'blacker than thou', as the old civil rights phrase goes. Even well-to-do blacks voted for Barry as a way of twisting the tail of the white establishment. The soon-to-be mayor had a message for all the white Washingtonians who were mortified by his victory: 'Get used to it.'

Half a century ago, the sociologist Gun- nar Myrdal wrote in his classic treatise on race relations, An American Dilemma, that

the American Negro does not feel confident towards a legal order he regards as inequitable. He feels a sense of solidarity against the law and the police so that the arrested Negro acquires the prestige of a vic- tim, hero, or martyr. There is a pride in not giving up a fellow Negro to the police.

Sadly, what the Simpson case and these other examples show is that the situation has not changed. Whites regard this behaviour as inexplicable, paranoid, self- destructive; blacks refusing to rise from their status as victims. The white chatter- ing classes go on and on about the dearth of positive black role models, and how sad it is that the black community embraces a rogues' gallery of sociopathic athletes and celebrities.

But what the opinion polls about O.J. Simpson and the real votes for Barry sug- gest is that white and black Americans do not live in the same country. They reveal that it is impossible to overestimate the resentment that even educated, well-to-do blacks harbour against the system. These middle-class blacks probably think O.J. is guilty and that it is a shame that Marion Barry has to flaunt his dirty laundry in public, but they feel compelled to show a racial solidarity with their down-and-out brothers and sisters.

While whites may believe black charges of a white racist conspiracy are absurd and perpetuate a culture of victimhood, the popularity of what might be called ghetto myths is rising. In her book I Heard it Through the Gravevine: Rumour in African- American Society, Patricia Turner writes that as many as a quarter of American blacks believe some variations of the fol- lowing: that crack-cocaine is being dis- tributed in inner cities by white politicians in order to thin out the black urban popu- lation; that a cabal of Jewish bankers ran the slave trade and now control the world's financial markets; and that Aids is an invention of white doctors in an effort to perpetrate genocide against the black pop- ulation. But the charges of racism conform all too well even with their experience.

The pool of prospective jurors in the Simpson case is 40 per cent black; O.J. will be hoping his lawyers ensure that a couple of these folks make it on to his panel of 12 peers.

Richard Stengel is a contributing editor of Time magazine.

Previous page

Previous page