Easter in El Salvador

Richard West

San Salvador The death and resurrection of Christ can seldom have been remembered with such solemnity and fervour as this year in El Salvador, a country named in honour of Christ, the Saviour. It is not a blasphemy to compare Christ's agony with that of a country caught in a civil war that has not spared even San Salvador Cathedral. Last March Archbishop Romero was shot dead at the altar, during Mass, and last Palm Sunday, some 20 mourners were killed on the steps outside the cathedral. San Salvador is the other side of the world from Jerusalem, nearly 2000 years have passed since the Crucifixion, but nobody who attended Easter services here could fail to have seen the relevance of the Christian message.

It is not a beautiful or imposing cathedral; earthquakes are among the misfortunes visited on this country, and the old town of San Salvador vanished in 1854. The present cathedral is still under construction, with metal bars jutting out of the reinforced concrete, but it will certainly be an eyesore even when it is finished. The interior decoration consists of some crude wooden statuary; by the doorways are open spaces (through one of which, Romero may have been shot); and the dove of peace above the altar (seen hoving over a map of the Western hemisphere), at first looks more like an eagle. But thellgliness of the cathedral is more than redeemed by the dignity and serenity of the congregation, almost all of them brown-skinned Indians, humbly dressed, but serene and proud. On Good Friday, I thought of the saying in Conrad's Central American novel Nostromo — 'God for men, religions for women' — but both sexes were represented in equal numbers on Easter Day, The Sunday service followed the new rites of the Church, with the vernacular liturgy, and the Creed in the first person plural — We believe. The hymns were sad Indian folk songs, accompanied by an accordion. And after the service, as is habitual now in Catholic churches outside countries like Ireland, the congregation were asked to shake hands with their neighbours. The acting archbishop Arturo Rivera y Damas preached in favour of peace and justice (a slogan adopted by certain left-wing Catholics) but quoted at length Pope John Paul II, whom left-wing Catholics do not follow. After the service, much of the congregation gathered to pray at the tomb of Archbishop Romero, a plain wooden box covered with red and white carnations. An inscription says: 'Your death comes without warning. But death is a seed when the people stand behind'.

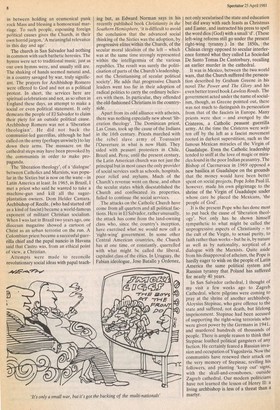

It would be wrong to deduce from what I have said that the services at San Salvador express some kind of political folk religion, approved by 'liberation theologians'. This kind of left-wing concern with justice and peace in the 'third world' is fashionable now in the United States and Europe, and tends to pin its revolutionary hopes on El Salvador. In some of the Protestant churches, too, we know the phenomenon of the trendy dean who passes the offertory plate round for Latin American terrorists — in between holding an ecumenical punk rock Mass and blessing a homosexual mar riage. To such people, espousing foreign political causes gives the Church, in their own horrid jargon, 'A meaningful relevance in this day and age'.

The church in San Salvador had nothing in common with such bathetic heresies. The hymns were set to traditional music, just as our own hymns were, and usually still are. The shaking of hands seemed natural and, in a country savaged by war, truly significant. The prayers for Archbishop Romero were offered to God and not as a political protest. In short, the services here are spiritual celebrations and not, as so often in England these days, an attempt to make a social or even political statement. It only demeans the people of El Salvador to claim their piety for an outside political cause. Archbishop Romero was not a 'liberation theologian'. He did not back the communist-led guerrillas, although he had called on the army (perhaps unwisely) to lay down their arms. The massacre on the cathedral steps may have been provoked by the communists in order to make propaganda.

The 'liberation theology', of a 'dialogue' between Catholics and Marxists, was popular in the Sixties but is now on the wane — in Latin America at least. In 1965, in Brazil, 1 met a priest who said he wanted to take a machine-gun and kill all the sugarplantation owners. Dom Helder Camara, Archbishop of Recife, (who had started off as a kind of fascist) became a world-famous exponent of militant Christian socialism. When I was last in Brazil two years ago, one diocesan magazine showed a cartoon of Christ as an urban terrorist on the run. A Colombian priest became a successful guerrilla chief and the papal nuncio in Havana said that Castro was, from an ethical point of view, a Christian.

Attempts were made to reconcile revolutionary social ideas with papal teach ing but, as Edward Norman says in his recently published book Christianity in the Southern Hemisphere, 'it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the advanced social thinking of the Sixties was the adoption, by progressive elites within the Church, of the secular moral idealism of the left — which was at the same time strongly represented within the intelligentsia of the various republics. The result was surely the politicisation of parts of the Church's leadership, not the Christianising of secular political society'. He adds that progressive Church leaders went too far in their adoption of radical politics to carry the ordinary believ ers with them. In particular, they offended the old-fashioned Christians in the countryside.

Apart from its odd alliance with atheists, there was nothing especially new about 'liberation theology'. The Dominican priest, Las Cosas, took up the cause of the Indians in the 16th century. Priests marched with the rebel slave army of Toussaint l'Ouverture in what is now Haiti. They sided with peasant protesters in Chile, Brazil and, Peru; until the present century, the Latin American church was not just the principal but in most cases the only provider of social services such as schools, hospitals, poor relief and asylums. Much of the Church's revenue went on these, and often the secular states which disestablished the Church and confiscated its properties, failed to continue the social services.

The attacks on the Catholic Church have come from all quarters and all political factions. Here in El Salvador, rather unusually, the attack has come from the land-owning class who, since the country's inception, have exercised what we would now call a 'right-wing' government. In some other Central American countries, the Church has at one time, or constantly, quarrelled with what might be called the liberal, capitalist class of the cities. In Uruguay, the Fabian ideologue, Jose Batalle y Ordonez, not only secularised the state and education but did away with such feasts as Christmas and Easter, and instructed his press to spell the word dios (God) with a small 'd'. (These left-wing reforms still go under the present right-wing tyranny.) In the 1850s, the Chilean clergy opposed to secular interference formed what they called La Sociedad De Santo Tomas De Cantorbury, recalling an earlier murder in the cathedral.

It was in Mexico, between the two world wars, that the Church suffered the persecution described by Graham Greene in his novel The Power and The Glory and his even better travel book Lawless Roads. The government acted under the name of socialism, though, as Greene pointed out, there was not much to distinguish its persecution from that of the fascists in Europe. Many priests were shot — and avenged by the Cristeros, a Catholic peasant guerrilla army. At the time the Cristeros were written off by the left as a fascist movement rooted in darkest superstition, such as the famous Mexican miracles of the Virgin of Guadalupe. Even the Catholic leadership tended to sniff at the love of magic or miracles found in the poor Indian peasantry. The Bishop of Cuernavaca in 1969 opposed a new basilica at Guadalupe on the grounds that the money would have been better spent on social projects. Pope John Paul II, however, made his own pilgrimage to the shrine of the Virgin of Guadalupe under whose care he placed the Mexicans, 'the people of God'.

It is the present Pope who has done most to put back the cause of 'liberation theology'. Not only has he shown himself sympathetic to what might be called the unprogressive aspects of Christianity — to the cult of the Virgin, to sexual purity, to faith rather than works but he is, by nature as well as by nationality, sceptical of a dialogue with the Marxists. Quite aside from his disapproval of atheism, the Pope is hardly eager to wish on the people of Latin America the same political system and Russian tyranny that Poland has suffered for nearly 40 years.

In San Salvador cathedral, I thought of my visit a few weeks ago to Zagreb Cathedral, where pilgrims were coming to pray at the shrine of another archbishop, Aloysius Stepinac, who gave offence to the state and suffered, not death, but lifelong imprisonment. Stepinac had been accused of supporting the right-wing terrorists who • were given power by the Germans in 1941, and murdered hundreds of thousands of people. There is ample reason to think that Stepinac loathed political gangsters of any faction. He certainly feared a Russian invasion and occupation of Yugoslavia. Now the communists have renewed their attack on the very memory of Stepinac, reviling his followers, and planting 'keep out' signs, with the skull-and-crossbones, outside Zagreb cathedral. Our modern politicians have not learned the lesson of Henry H: a living archbishop is less of a threat than a martyr.

Previous page

Previous page