Exhibitions 2

Wu Guanzhong: A 20th-Century Chinese Painter (British Museum, till 10 May)

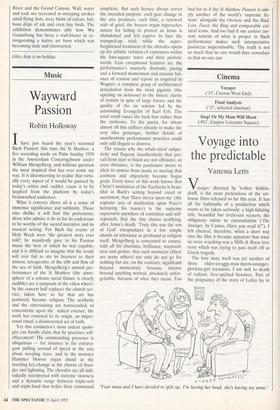

. . . towards a new tradition

John Henshall

At and politics rarely prove compati- ble bedfellows; almost inevitably, the for- mer upsets the latter, which then retaliates at culture in general with a ferocity out of all proportion to the ideological wrongs committed, real or imaginary. The career of Wu Guanzhong, an eminent Chinese artist enjoying his first European showing at the age of 73, illustrates the point per- fectly. It is also testimony to the stoic endurance with which an artist can with- stand everything from the disruption caused by armed invasion of his country to the privations of internal exile there. Wu

'Cloudy Mountains', 1988, ink and colour on paper, by Wu Guanzhong experienced both, yet has still led the way to a successful fusion of the traditional art of his homeland with invigorating influ- ences from far beyond its shores.

Wu Guanzhong was born into a farming family in Jiangsu and went on to study at the Hangzhou Academy of Art. At the end of his first year there, the Sino-Japanese war began, and Hangzhou fell to the invaders just after Wu, his lecturers and fellow students had begun the long trek west to Sichuan, where Wu graduated. He had also developed an intense interest in European and especially French art, and in 1946, when peace came, he won a scholar- ship to study in Paris.

Within three days of arriving, Wu had visited almost every major gallery and museum. During his time in France he was extremely poor, found French difficult and suffered racial discrimination. However, he absorbed sufficient of the essence of West- ern art to be able to return to China in 1950 with a mission: to marry the fresh breath of Westernism, and of abstraction and formalism in particular, with the tradi- tional Chinese guohua, the calligraphy- based 'national painting' style. Since the early 1900s Chinese artists and critics had agreed that guohua, time-honoured and often exquisitely beautiful as it was, needed radical revitalisation if it was to be a suit- able art form for 20th-century China.

Qn his return home, Wu was appointed to lectureships first at Peking's Qingnua University, then at its Central Institute of Arts and Crafts. His students were as eager to learn about Van Gogh and Cezanne as he was to teach them. However, when the Cultural Revolution began in 1966 Wu was soon denounced by the party faithful as a bourgeois capitalist who poisoned youthful minds. Even the most unquestioning party hacks agreed China needed a new art form, but they wanted a Chinese version of Sovi- et Socialist Realism. Wu was one of thou- sands of intellectuals sent for 're- education'; he had to live the life of a peas- ant in remote northern China. Though his wife was being 're-educated' within walking distance, Wu was forbidden to see her for two years. When he was eventually allowed to paint again, he was also allowed to see her once more, and she would crouch before him obligingly, so he could use her back to rest his makeshift easel on. Wu and other exiled artists jokingly referred to themselves as members of the Dung-basket or Cow-pen school of art. Then in 1972 Wu and others were called back to Peking by Zhou Enlai, until whose death in 1976 they could paint more or less what they liked.

After Zhou's death, Mao's regime began a new cultural crackdown. However, the liberal interlude of the 'Peking Spring' saw non-conformist artists called 'the Stars' hold two major exhibitions which criticised the regime openly. Then with the 1980s came Wu's most fruitful decade. It is from this period that most of the works in this show originate. Wu had been slightly too old to join the artistic challenges to author- ity in the 1970s, and managed to keep free and painting during the disoriented 1980s which culminated in the brutish massacre in Tienanmen Square in 1989. These events prevented a younger generation from absorbing successfully the artistic influ- ences which had flowed in since China's opening up to the West in the 1970s, and Wu remained in his country's avant-garde.

The most successful of the works on dis- play are in Wu's 'new guohua', his personal blend of Western influences from Impres- sionism to Cubism with the calligraphic tra- ditional art of the older China. It is distinguished by its kinetic intensity, con- trasting bold strokes and delicate detail, and its use of potentially clashing colours: blacks, crimsons and greens. The guohua

style is ink and colour on paper; there are no oils from Wu's early career here, though

there are a number from the 1970s on. They depict France, New Delhi and Hong Kong, but are not as assuredly successful as the 'new guohua'.

In this medium, Wu skilfully imbues his work with an almost physical sense of movement and momentum, as in his visions of the Great Wall of China, the Yangzi River and the Grand Canyon. Wall, water and rock are recreated in sweeping strokes amid flying dots, stray blobs of colour, bul- bous drips of ink and even tiny birds. The exhibition demonstrates ably how Wu Guanzhong has been a trail-blazer in re- invigorating a native art form which was becoming stale and introverted.

Previous page

Previous page