Bankers' trusts

JOHN BULL

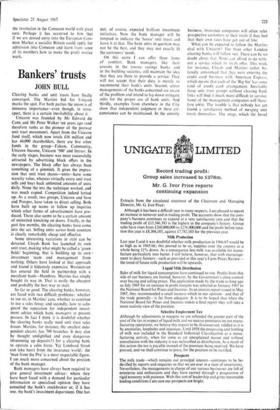

Clearing banks and unit trusts have finally converged. The Martins bid for Unicorn marks the spot. For both parties the union is of immense importance—even though, in retro- spect, there is a certain inevitability about it.

Unicorn was founded by Mr Edward du Cann and Mr Peter Walker ten years ago (and therefore ranks as the pioneer of the postwar unit trust movement). Apart from the Unicorn fund itself, which now totals f16 million and has 44,000 shareholders, there are five other funds in the group—Falcon, Community, Unicorn Income, Unicorn '500' and Intrust. In the early stages, business was most successfully attracted by advertising block offers in the newspapers. The block offer has always been something of a gimmick. It gives the impres- sion that unit trust shares—units—have some scarcity value, whereas virtually every unit trust sells and buys back unlimited amounts of units daily. None the less the technique worked, and was much copied. Competition indeed honed up. As a result, two groups, Unicorn and Save and Prosper, have taken to direct selling. Both have built up teams to follow up inquiries which other forms of advertisement have pro- duced. There also seems to be a certain amount of uninvited knocking on doors. Finally, in the past few months, the clearing banks have come into the act. Selling units across bank counters is clearly remarkably cheap and effective.

Some interesting variations in style can be detected. Lloyds Bank has launched its own unit trust, making what might be called a 'green fields' beginning, that is building up its own - investment team and management from nothing. Others have looked at that approach and found it hideously expensive. Westminster has entered the field in partnership with a merchant bank—Hambros. Martins has simply bought its way in. That is easily the cheapest and probably the best way to start.

So far so good. The clearing banks, however, are faced with two difficult problems: whether to use or, in Martins' case, whether to continue to use a sales force; and secondly, how to safes guard the reputation for independent invest- ment advice which bank managers at present possess. In fact I think it is doubtful whether the clearing banks really need unit trust sales forces. Martins, for instance, the smallest incle- pendent clearer, has 700 branches. It may also be thought undignified and even dangerous (drumming up deposits?) for a clearing bank to operate a sales force. Yet Lombard Street can take heart from the insurance world: the 'man from the Pru' is a most respectable figure. I am much more concerned about the position of the bank manager.

Bank managers have always been required to give general investment advice: where they have been faced with a demand for particular information or specialised opinion they have consulted the bank's stockbroker or, if it has one, the bank's investment department. One has

not, of course, expected brilliant investment initiatives. Now the bank manager will be tempted to indicate the 'house' unit trusts and leave it at that. The bank units in question may not be the best, and they may not exactly fit the customers' needs.

On this score I can offer three items of comfort. Bank managers, like their cousins in the trustee savings banks and in the building societies, still maintain the idea that they are there to provide a service. They will not accept that their duty is merely to recommend their bank's units. Second, senior managements of the banks concerned are aware of the problem and intend to lay down stringent rules for the proper use of bank units. And thirdly, examples from elsewhere in the City show that independent judgment in these cir- cumstances can be maintained. In the annuity business, insurance companies will often refer prospective customers to their rivals if they feel that their own rates have got out of line.

What can be expected to follow the Martins deal with Unicorn? The three other London clearing banks 1\ ill follow suit. There can be no doubt about that. None can afford to do with- out a ser% ice w hich its ri% a Is offer. This week for instance, 1.1o■ ds and Martins rather be- latedly announced that they were entering the credit card business v, ith American Express, which means that each of the 'Big Six' has some kind of credit card arrangement. Inevitably those unit trust groups without clearing bank links will find it much more difficult to survive. Some of the management companies will there- fore unite. The trouble is that nobody has yet found. a satisfactory method of merging unit trusts themselves. The snags, which the Jessel

regional trusts may prove the first to overcome, are largely to do with taxation.

And the investor, what advantage is clearing bank participation to him? I am bound to say, very little. Units will be more widely available. But management charges are unlikely to come down. And as for market performance, etandards will remain where they are now- Sompetent but not exceptional.

Previous page

Previous page