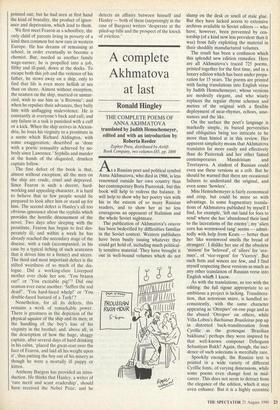

A complete Akhmatova at last

Ronald Hingley

THE COMPLETE POEMS OF ANNA AKHMATOVA translated by Judith Hemschemeyer, edited and with an introduction by Roberta Reeder

Zephyr Press, distributed by Airlift Book Company, two volumes £65, pp. 1600

As a Russian poet and political symbol Anna Akhmatova, who died in 1966, is less renowned outside her own country than her contemporary Boris Pasternak, but this book will help to redress the balance. It will help to show why her poetry vies with his in the esteem of so many Russian readers, and to show her as no less courageous an opponent of Stalinism and the whole Soviet nightmare.

The publication of Akhmatova's oeuvre has been bedevilled by difficulties familiar in the Soviet context. Western publishers have been busily issuing whatever they could get hold of, including much political- ly sensitive material. They have brought it out in well-bound volumes which do not

slump on the desk or smell of stale glue. But they have lacked access to extensive archives available to Soviet editors — who have, however, been prevented by cen- sorship (of a kind now less prevalent than it was) from fully exploiting the material in their shoddily manufactured volumes.

The result has been a confusion which this splendid new edition remedies. Here are all Akhmatova's traced 725 poems, printed together for the first time, and in a luxury edition which has been under prepa- ration for 15 years. The poems are printed with facing translations into English verse by Judith Hemschemeyer, whose versions are modestly elegant, and who wisely replaces the regular rhyme schemes and metres of the original with a flexible deployment of near-rhymes, echoes, asso- nances and the like.

On the surface the poet's language is markedly simple, its buried perversities and obliquities being too intricate to be more than hinted at in this review. Her apparent simplicity means that Akhmatova translates far more easily and effectively than do Pasternak and her other famed contemporaries Mandelstam and Tsvetayeva. A student of Russian could even use these versions as a crib. But he should be warned that there are occasional failures to understand the original, and even some 'howlers'.

Miss Hemschemeyer is fairly economical and crisp, but could be more so with advantage. In some fragmentary transla- tions of Akhmatova published by myself I find, for example, 'left our land for foes to rend' where she has 'abandoned their land to the lacerations of the enemy'; my 'alien corn has wormwood tang' seems — admit- tedly with help from Keats — better than her 'like wormwood smells the bread of strangers'. I dislike her use of the obsolete 'minion' for 'beloved', of 'allees' for 'ave- nues', of 'vice-regent' for 'Viceroy'. But such frets and winces are few, and I find myself respecting these versions as much as any other translation of Russian verse into English which I know.

As with the translations, so too with the editing: the full rigour appropriate to so ambitious a project is lacking. Translitera- tion, that notorious snare, is handled in- consistently, with the same character appearing as 'Otrepiev' on one page and as the absurd 'Otropov' on others, while Villa-Lobos's Bachianas Brasileiras pop up in distorted back-transliteration from Cyrillic as the grotesque 'Brazilian bakhiana'; perhaps they were inspired by that well-known composer Dzhogann Sebastiyan Bakh? Again, though, the inci- dence of such solecisms is mercifully rare.

Spookily enough, the Russian text is printed in a wide variety of different Cyrillic fonts, of varying dimensions, while

some poems even change font in mid- career. This does not seem to detract from

the elegance of the edition, which it may even enhance. But it is a highly eccentric procedure for which no editorial explana- tion at all seems to be offered.

Warts and all, this is the most attractive edition of any Russian poet known to me, and certainly outranks what may be its nearest parallel: Vladimir Nabokov's four- volume presentation of Pushkin's Yevgeny Onegin. But when I look up at my shelves and see Aeschylus (ed. Fraenkel), Lucre- tius (ed. Bailey) and Dante (ed. Singleton) — all of which incorporate translations, though not into verse — I mourn the extent to which Russian studies still seem to operate in blissful unawareness of the very concepts of scholarly precision and detach- ment.

As for the assertion made by one contri- butor to this volume, that `Akhmatova's poetry ranks with the best of world poetry', this is a claim which — fine poet though she was — she would never have made for herself. It is the kind of oh-so-Russian hype that makes one wonder how much of the world's best poetry the speaker actually knows.

Previous page

Previous page