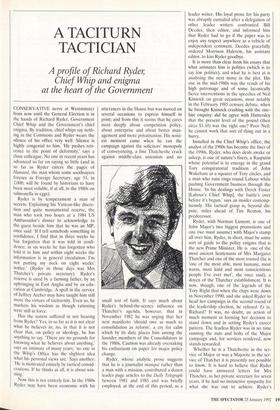

A TACITURN TACTICIAN

A profile of Richard Ryder, Chief Whip and enigma at the heart of the Government

CONSERVATIVE nerve at Westminster from now until the General Election is in the hands of Richard Ryder, Government Chief Whip and the Government's chief enigma. By tradition, chief whips say noth- ing in the Commons and Ryder wears the silence of his office very well. Silence is highly congenial to him. 'He pushes reti- cence to the point of deformity,' says a close colleague. No one in recent years has advanced so far on saying so little (and in so far as Ryder enters the pages of Hansard, the man whom some soothsayers foresee as Foreign Secretary, age 51, in 2,000, will be found by historians to have been most voluble, if at all, in the 1980s on salmonella in eggs).

Ryder is by temperament a man of secrets. Explaining his Vatican-like discre- tion and quite monumental reserve, the man who took two hours at a 1984 US Ambassador's dinner to acknowledge to the guest beside him that he was an MP, once said: 'If I tell somebody something in confidence, I find that in three weeks he has forgotten that it was told in confi- dence; in six weeks he has forgotten who told it to him and within eight weeks the information is in general circulation. I'm not putting my neck on eight weeks' notice.' (Ryder in those days was Mrs Thatcher's private secretary). Ryder's reserve is sired by a farming father, by an upbringing in East Anglia and by an edu- cation at Cambridge. A spell in the service of Jeffrey Archer may have taught him still more the virtues of taciturnity. Even so, he markets his wisdom as though rationing were still in force.

Has the nation suffered in not hearing from Ryder? Yes, in so far as it is not clear what he believes in; no, in that it is not clear that, on policy or ideology, he has anything to say. 'There are no grounds for knowing what he believes about anything,' says an intimate of many years; 'no one in the Whip's Office has the slightest idea what his personal views are.' Says another: 'He is motivated entirely by tactical consid- erations. If he thinks at all, it is about win- ning.'

Now this is not entirely fair. In the 1980s Ryder may have been economic with his utterances in the House but was moved on several occasions to express himself in print; and from this it seems that he cares most deeply about competition policy, about enterprise and about better man- agement and more privatisation. His noisi- est moment came when he ran the campaign against the solicitors' monopoly of conveyancing, a fine Thatcherite crack against middle-class unionism and no

small test of faith. It says much about Ryder's behind-the-scenes influence on Thatcher's agenda, however, that in November 1982 he was urging that her next manifesto 'should owe as much to consolidation as reform', a. cry for calm which by its date places him among the founder members of the Consolidators in the 1980s. Caution was already overtaking his enthusiasm on paper for major policy change.

Ryder, whose analytic prose suggests that he is a journalist manqué rather than a man with a mission, contributed a dozen leader page articles to the Daily Telegraph beween 1981 and 1985 and was briefly employed, at the end of this period, as a

leader writer. His loyal prose for his party was abruptly curtailed after a delegation of other leader writers confronted Bill Deedes, then editor, and informed him that Ryder had to go if the paper was to enjoy any respect anywhere as a vehicle of independent comment. Deedes gracefully ordered Morrison Halcrow, his assistant editor, to kiss Ryder goodbye.

It is more than clear from his essays that what animates him is politics (which is to say low politics), and what he is best at is analysing the next move in the plot. His rise in the mid-1980s was the result of his high patronage and of some laconically fierce interventions in the speeches of Neil Kinnock on great occasions, most notably in the February 1985 censure debate, when he brought Kinnock crashing with the one- line enquiry: did he agree with Hattersley that the present level of the pound (then circa $1.10) was the right one? Poor Neil: he cannot work that sort of thing out in a hurry.

Installed in the Chief Whip's office, the analyst of the 1980s has become the fixer of the 1990s. Ryder, who does deals awake or asleep, is one of nature's fixers, a Rasputin whose potential is to emerge in the grand Tory conspiratorial tradition of John Wakeham as a squarer of Tory circles, and a man who runs rings round Labour while pushing Government business through the House. 'In his dealings with Derek Foster [Labour's Chief Whip], the battle's over before it's begun,' says an insider contemp- tuously. His tactical grasp is, beyond dis- pute, miles ahead of Tim Renton, his predecessor.

Ryder, with Norman Lamont, is one of John Major's two biggest promotions and one (we must assume) with Major's stamp all over him. Ryder, in short, must be some sort of guide to the policy enigma that is the new Prime Minister. He is one of the most ancient lieutenants of Mrs Margaret Thatcher and one of the most trusted (he is 'one of the most able, most humane, most warm, most kind and most conscientious people I've ever met', she once said), a doyen of the Thatcher establishment. It is now, though, one of the legends of the Tory Right that when the chips were down in November 1990, and she asked Ryder to head her campaign in the second round of

the leadership election, he refused. Et tu,

Richard? It was, no doubt, an action of much moment in forming her decision to stand down and in setting Ryder's career pattern. The fearless Ryder was in no time running the nuts and bolts of the Major campaign and, for services rendered, now stands rewarded.

Whether he is a Thatcherite in the ser- vice of Major or was a Majorite in the ser- vice of Thatcher it is presently not possible to know. It is hard to believe that Ryder could have answered letters for Mrs Thatcher, as her private secretary for seven years, if he had no instinctive sympathy for what she was out to achieve. Ryder's attraction to Major in 1990 was no doubt a personal one — they share a sense of humour and a deflationary temperament, and are good friends — but politically its main component looks like an attachment to the main chance. It took no vast intelli- gence to work out, once Thatcher had stood down, that Heseltine was too contro- versial and Hurd too old and that Major must win, just as no membership of Mensa will be offered to those who guess that the Tory Leader of the Opposition, should one be needed later in 1992, will be Michael Heseltine. Whether Ryder would serve Heseltine as loyally as he serves Major, and did serve Thatcher, is part of the cloud at the heart of the man.

It is, perhaps, a parable about Ryder (or at least another part of right-wing demonography) that he attended the inau- gural meeting of the No Turning Back group and promptly backed away as soon as his name got out. A list of members was published in the obscure quarter of the magazine Accountancy Age; discretion was suddenly the better part of valour and off he went, muttering that he could 'achieve the same objective by different means' or something like it.

Is he now distressed as Thatcher's eco- nomic revolution is betrayed by a £20 bil- lion Public Sector Borrowing Requirement and the Heseltine Council Tax? 'Who knows?' says a senior minister of long acquaintance who sees him daily. He showed no loyalty to the Community Charge (but few did); his line in soothing Thatcherites who see the mounting PSBR as throwing away everything she fought for is to say, 'All very regrettable of course and it's not Government policy to continue with a PSBR of this size and once interest rates are down and the recession's over, we'll be back in the black.' On Europe, Ryder's line in flannel is regarded by those backbenchers whom he sought to persuade to support the Maastricht deal as worthy bf St Thomas Aquinas.

All that said, Ryder remains the master of tactics, a near genius in soothing and shushing the directionless flock of sheep that is the Tory party in the Commons. Outbreaks of sheep hysteria against John Major, as fortunes have risen and plunged in the polls and the slaughterhouse looms for many, have been remarkably few. It is another part of the Ryder enigma that it is far from clear how he does it. He is as far from Ian Gow in his management theory of MPs as it is possible to get. He is not a mixer in the House; he is not gregarious and since becoming Chief Whip has used his table in the Members' Dining Room only on a handful of occasions; he goes home nightly to spend time with his fami- ly, making it even harder for MPs to get to know him. He shares the hypersensitivity to criticism common among this Govern- ment's grandees. He is said by colleagues to spend hours reading the papers (even, presumably, publications as recherché as Accountancy Age) for signs of adverse comment.

He acquired, during the leadership cam- paign, a taste for telephoning editors. He is not above fretting about journalists, and seems to spend undue time worrying about this subterranean and inconsequen- tial breed. He also spends hours on the telephone to wayward members of the Commons herd, notably at weekends. 'He says little, listens long and looks owlishly wise,' says one MP in explanation of the

Ryder technique in man- handling his vote. The style (enhanced by the innate cheerfulness of a boy who was a social sportsman in youth) must work: since the mass assassination of Mrs Thatcher by the 152 sheep in 1990, the bleating herd has been calm to the point of passivity. It has not, of course, been fed much raw ideological meat to stir it up; it says much that the Joyriders Bill is the main intellectual fare of the present ses- sion.

He is, all this said, a genuinely happy, friendly, cheerful chap. Whether he is your friend tomorrow as well as today, John Major, as well as many others, will be in erested to find out.

'Eddie, are we interested in an impersonator of Elvis as he would appear today?'

Previous page

Previous page