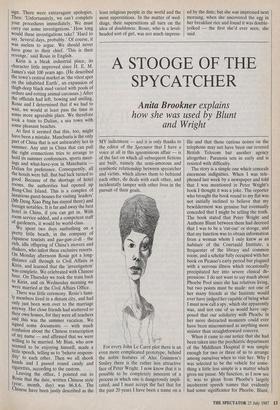

GETTING MARRIED IN MANCHURIA

Giles Mathews describes how

his wedding to a Chinese girl caused problems

ON Thursday we went to the Civil Affairs Office. Like most substantial buildings in Manchuria, this one dated from the Japanese occupation. It has certainly not seen a coat of paint since Liberation. Running round all the interior walls was a sort of dado of black grime reaching to shoulder height, where generations of citizens had leaned while waiting for the resolution of their Civil Affairs. (Just what Affairs the office dealt with, other than marriages between Chinese and foreigners, I never discovered.) The wooden floors were worn to concavity like the flagstones of some mediaeval monastery. Twenty-five- watt bulbs hung from the high ceiling.

Our case was in the hands of two officials, Mr Bian and Mr Chen. This turned out to be a good cop, bad cop arrangement. Mr Bian chuckled over our papers, declared them in order, and began asking me personal questions — a friendly courtesy in China. Mr Chen was much more reserved. He watched our dealings with Mr Bain impassively from behind a veil of tobacco smoke, then, when our papers passed to him, scrutinised them long and silently. When at last he spoke, it was to raise irritating little points of order. Did Rosie's parents approve of the mar- riage? But wasn't their approval required in writing? He allowed himself to be persuaded that it was not. What about Rosie's unit? Had they agreed to release her? This went on for some time. Rosie became more and more flustered, Mr Bian soothed, while I sat there in the yellow gloom smiling through clenched teeth — a basic survival skill in the People's Repub- lic.

At last Mr Chen decided that our papers were indeed in order. Of course they were; I had made very sure of that before coming to China for the marriage. There was one thing we hadn't known, though. A Chinese marriage certificate must include a photo- graph of the bride and groom. We had no photographs. We took directions to the nearest studio and agreed to return to the Civil Affairs Office the following day.

This was all very smooth sailing. Next day things became more Chinese. When we presented ourselves at the office, there was nobody there! The street door was open, but all the interior doors seemed to be locked. No officials were in sight.

We patrolled dim corridors, and at last found a caretaker. The officials hadn't come, he said. Why not? A shrug: Was there anybody who could deal with our matter? He would try to find someone. He disappeared. We waited. People drifted in from the street to stare at us. Then an old peasant woman shuffled in. To judge from the amount of mud on her trousers, she had come from one of the outlying villages.

`Where are the officials?' she asked. We told her that they hadn't come today, no-one knew why. She gave out a long sigh of exasperation. 'Ail And how many more times must' I come here, then? Can any- body tell me?' Nobody could.

At last the caretaker returned. Chief Wang would see us. We climbed a wooden staircase. Chief Wang had an office to himself on an upper floor. He stood to greet us with a fine display of gravitas. He apologised. The officials had taken leave without permission. It was inexcusable. We had been seriously inconvenienced. He would find those officials. They would come to my guest-house tomorrow morn- ing. Then everything would be accom- plished. We thanked him and backed out.

We had, of course, made a serious mistake. Early on Saturday morning a little group of officials arrived at my guest-house in Rosie's unit. Mr Bian and Mr Chen were among them. Mr Bian acted as spokesman. He was exceedingly polite — a very bad sign. There were extravagant apologies. Then: 'Unfortunately, we can't complete your procedures immediately. We must carry out some investigations.' How long would these investigations take? 'Hard to say. Several days, probably.' Of course, it was useless to argue. We should never have gone to their chief. 'This is their revenge,' said Rosie in English.

Kirin is a bleak industrial place, its character little improved since H. E. M. James's visit 100 years ago. (He described the town's central market as 'the vilest spot on the inhabited Earth', an expansion of thigh-deep black mud varied with pools of ordure and rotting animal carcasses.) After the officials had left, bowing and smiling, Rosie and I determined that if we had to wait, we would at least pass the time in some more agreeable place. We therefore took a train to Dalian, a sea town with some pleasant beaches.

At first it seemed that this, too, might have been a mistake. Manchuria is the only part of China that is not unbearably hot in summer. Any unit in China that can pull the right connections tries to arrange to hold its summer conferences, sports meet- ings and what-have-you in Manchuria Dalian for preference. Consequently, all the hotels were full. But bad luck turned to good. Because of the shortage of hotel rooms, the authorities had opened up pang-Chui Island. This is a complex of luxurious guest-houses for visiting 'leaders' (Mr Deng Xiao Ping has stayed there) and foreign notables. It is far and away the best hotel in China, if you can get in. With room service added, and a competent staff of gardeners, it would be world-class. We spent two days sunbathing on a pretty little beach, in the company of Japanese tourists and gao-gan-zi-di - the rich, idle offspring of China's movers and shakers, who infest these exclusive resorts. On Monday afternoon Rosie got a long- distance call through to Civil Affairs in Kirin, and learned that the 'investigation' was complete. We celebrated with Chinese beer. On Thursday we took the train back to Kirin, and on Wednesday morning we were married at the Civil Affairs Office.

There was little ceremony. Rosie's fami- ly members lived in a distant city, and had only just been won over to the marriage anyway. Her close friends had scattered to their own homes, for they were all teachers and this was the summer vacation. We signed some documents — with much confusion about the Chinese transcription Of my name — and affirmed that we were Willing to be married. Mr Bian, who now seemed to be enjoying himself, made a little speech, telling us to 'behave respons- ibly' to each other. Then we all shook hands and I passed round candy and cigarettes, according to the custom. Leaving the office, I pointed out to Rosie that the date, written Chinese style (year, month, day) was 86.8.6. The Chinese have been justly described as the least religious people in the world and the most superstitious. In the matter of wed- dings, their superstitions all turn on the idea of doubleness. Rosie, who is a level- headed sort of girl, was not much impress- ed by the date; but she was impressed next morning, when she uncovered the egg in her breakfast rice and found it was double- yolked — the first she'd ever seen, she said.

Previous page

Previous page