ARTS

Dance

Ashton's artistry

Julie Kavanagh Peter Schaufuss is our most enterprising — and some might add, opportunistic — dance director. His coup this season was not only to lure Makarova back to ballet after a year but to unearth a singular vehicle for her in Frederick Ashton's Apparitions, last performed 30 years ago. Ashton is extremely sceptical about the current zeal for 'exhuming' his early work. `It's like digging up Aunt Mabel to see if she's still pretty.' In the case of Apparitions he was confident of the score — Constant Lambert's orchestral arrangement of Liszt's piano pieces — but understandably wary that its ultra-Romantic plot would not hold up today. However, in Festival Bal- let's two performances of the work, Aunt Mabel emerged alive and well-preserved, if looking a little of her time. Of course Apparitions can't compete with a mature narrative work like A Month in the Country any more than Yeats's 'When you are Old' can be measured against 'The Tower'. But neither is it just a curiosity, to be seen once for the archives. It contains some fine choreography and confirms how early Ashton's personal style was consolidated.

Apparitions was born out of Saturday afternoon sessions that Ashton used to have with Constant Lambert, playing through Liszt's piano corpus. This revival is dedicated to Lambert, who was among the first to champion the composer at a time when Romantic music was out of vogue. Liszt's music was then considered overcharged, but Ashton loved its un- bridled emotional content and Lambert believed that the composer was, like De- bussy, a greater innovator than Stravinsky. For the libretto, Lambert adapted Ber- lioz's Symphonie Fantastique, about a poet's search for inspiration (embodied in the Woman in Ball Dress) through laudanum-induced fantasy landscapes. Robert Helpmann created the role of the Poet in 1936 and Margot Fonteyn was '1' Amour Supreme'. The ballet's central theme had personal significance for both Ashton and Lambert: although he didn't know it at the time, the choreographer had cast Fonteyn as his own creative muse; while Lambert was, as Ashton has said, `like the character in Apparitions . . . looking for the Ideal One' and had begun to fall in love with the 16-year-old dancer.

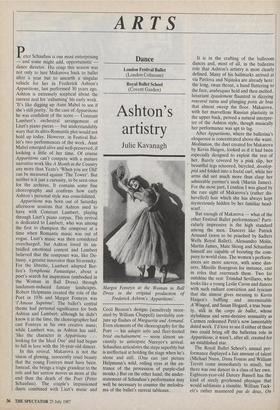

In this revival, Makarova is not the vision of glowing, innocently cruel beauty that the young Fonteyn must have been. Instead, she brings a tragic grandeur to the role and her sorrow moves us more at the end than the death of the Poet (Peter Schaufuss). The couple's impassioned duets combined with Liszt's music and Margot Fonteyn as the Woman in Ball Dress in the original production of Frederick Ashton's `Apparitions'.

Cecil Beaton's designs (sensitively recre- ated by William Chappell) inevitably con- jure up flashes of Marguerite and Armand. Even elements of the choreography for the Poet — his adagio solo and fleet-footed brise enchainement — seem almost un- cannily to anticipate Nureyev's arrival. Schaufuss articulates the steps superbly but is ineffectual at holding the stage when he's alone and still. (One can just picture Helpmann's wild, rolling eyes at the en- trance of the procession of purple-clad monks.) But on the other hand; the under- statement of Schaufuss's performance may well be necessary to counter the melodra- ma of the ballet's surreal tableaux. It is in the crafting of the ballroom dances and, most of all, in the ballerina role that Ashton's artistry is most clearly defined. Many of his hallmarks arrived at via Pavlova and Nijinska are already here: the long, swan throat, a hand fluttering to the face, arabesques held and then melted, luxuriant epaulement flaunted in dizzying renverse turns and plunging ports de bras that almost sweep the floor. Makarova, with her marvellous Russian plasticity in the upper back, proved a natural interpre- ter of the Ashton style, though musically her performance was apt to lag.

After Apparitions, where the ballerina's eloquence is concentrated above the waist, Meditation, the duet created for Makarova by Kevin Haigen, looked as if it had been especially designed to exploit the rest of her. Barely covered by a pink slip, her beautiful legs scissored, bicycled, develop- pal and folded into a foetal curl, while her arms did not much more than clasp her admirable partner's neck (Martin James). For the most part, I confess I was glued by the rare sight of Makarova's (rather dis- hevelled) hair which she has always kept mysteriously hidden by her familiar head- scarf.

But enough of Makarova — what of the other Festival Ballet performances? Parti- Cularly impressive is the high standard among the men. Dancers like Patrick Armand (soon to be poached by Sadlers Wells Royal Ballet), Alessandro Molin, Martin James, Matz Skoog and Schaufuss himself are capable of boosting the com- pany to world class. The women's perform- ances are more uneven, with some dan- cers, Mireille Bourgeois for instance, cast in roles that overreach them. Two far outshine the rest: Trinidad Sevillano, who looks like a young Leslie Caron and dances with such radiant conviction and lyricism that she almost gives meaning to Kevin Haigen's baffling and interminable A'Winged, and Susan Hogard, a true beau- ty, still in the corps de ballet, whose stylishness and semi-derisive sensuality as Carmen redeemed Petit's now lamentably dated work. I'd love to see if either of these two could bring off the ballerina role in Apparitions; it wasn't, after all, created for an established star.

The Royal Ballet School's annual per- formance displayed a fair amount of talent (Michael Nunn, Dana Fouras and William Trevitt come immediately to mind), but there was one dancer in a class of her own. Eighteen-year-old Darcey Bussell has the kind of steely greyhound physique that would sublimate a stumble. William Tuck- ett's rather mannered pas de deux, On Classicism, was a panegyric to her line, and she also gave a precocious account of Odile — but one which left me dubious about her potential as Odette. Like many young dancers today, born with what Makarova calls 'those cold, perfect bodies', her bril- liance is in her legs. Her arms are taut and expressionless and she lacks epaulement which, like shading on a drawing, adds nuance and dimension to dancing. It's a quality the Royal Ballet have always been admired for, but now it seems in danger of dying out. Even in Ashton's choreography — most noticeably in the girls' solos in his Swan Lake pas de quatre — the students showed little grasp of indigenous finesse. Surely Ashton ballerinas like Sibley and Seymour can be inveigled into handing on the torch? Otherwise, English classicism may not even outlive its creator.

Previous page

Previous page