THE ECONOMY & THE CITY

Dealing with the Deficit

By NICHOLAS DAVENPORT

'r is possible to doubt,' said the Bank of IEngland in its latest (June) bulletin, 'whether the public at large even now fully realise the extent of the crisis from which the country is emerging or accept its consequences.' Of course they don't. How can they be expected to read the technical jargon of the Bank's excellent bulletins? Even educated people would fail to understand the stuff if they had had no financial training. The man in the street may have heard on the TV that we have been buying too much abroad and selling too little, but when he walks into his superstore he will see tinned fruits from California, cheeses from France, veal from Holland, OW from Switzerland, in the same pro- fusion as before. It can't be so bad, he thinks, if the Government does nothing about it. And Mr. Callaghan has been saying that there has been a 'remarkable improvement' in the balance of payments. The trade returns in May may have been 'shocking,' but behind the monthly ups and downs, he said, a 'basically healthier position' is being established. To suggest otherwise you are likely to be called a traitor or conspirator by the First Secretary of State.

The truth of the matter is that the improve- ment in the current trading balance in the first quarter of the year, which Mr. Callaghan truly said was 'remarkable,' has not been maintained. Of course, imports jumped up for a special reason in May, the import surcharge having been cut from 15 per cent to 10 per cent at the end of April, but we are going to be pressed hard to

make a further cut at the next EFTA meeting in October. Of course, the Government is doing all it can to improve our industrial efficiency— through the 'Little Neddies'—but this is a long- term and difficult job. In 1954, for example, £336 million of business in the UK home market was taken by foreign machinery-makers—a third of them American—which must reflect on the tech- nical competitiveness of British manufacturers. The same applies to electrical engineering pro- ducts, where another sharp rise in imports has been seen. If, then, we are to endure for the time being a high rate of imports in semi- and finished manufactures because of domestic short- comings and a sluggish growth rate in exports because of the worsening world liquidity, it is no use pretending that we have yet emerged from our balance of payments crisis. We have got to live with it longer than we expected and we have got to take more radical measures.

Devaluation is ruled out. It would do nothing to solve our long-term industrial problems. De- flation and stagnation at home—through the use of the 10 per cent 'regulator' (increase in indirect taxes) and perhaps a 10 per cent Bank rate— would not help either, for it would shatter our industrial morale, raise our costs and make our goods still more uncompetitive. There is therefore a strong case for removing the 10 per cent sur- charge on imports and replacing it by temporary import quotas. This is allowable under the escape clauses provided in GATT and in the EFTA con- vention. Europe is familiar with the import quota device and the merit of it is that it can be made selective and need only be applied to the more desperate import cases. Of course, it brings a lot of work to the Board of Trade, but that depart- ment, if it is not asleep, should have been pre- paring for this possibility.

The Bank of England should also have been preparing for the possibility of more drastic monetary action to restrain imports. First, im- porters could be required to pay cash on delivery at the docks or airports. This restraint was tried out in Italy with remarkably quick results. Second, importers and exporters could be stopped from dealing in forward exchange. If they de- sired to cover a forward exchange commitment, they should be required to apply to the Bank of England, which for a certain fee—like an in- surance premium—would guarantee that they would be covered against any exchange loss. This would prevent the 'leads and lags' operations which were the main source of trouble in the autumn exchange crisis. The Bank cover would apply only to legitimate traders and manufac- turers of the UK—not to overseas residents of the sterling area. This would not prevent specu- lation abroad against the £, but it would limit speculation at home and prevent the merchant banks operating in the open exchange markets on behalf of UK 'leads and lags.' It is high time that such a scheme—propounded, I believe, originally by an acknowledged monetary expert, Harold Lever, MP—be seriously taken up by the authorities. It is pathetic to see them pursuing the old makeshifts of dearer and 'dearer money, which have been proved in the past to be useless. A return to the dark monetary ages is not the way to modernise Britain.

While Mr. George Brown's department is doing its best to improve the efficiency of British in- dustry, the Bank of England has been wisely preparing the ground for the finance of a pos- sibly lengthy deficit on the balance of payments.

It will Crel Wh whc Am end asst wit' out Ga S1,1 resi Go the liqi ing the rer £l, of the en: oh res

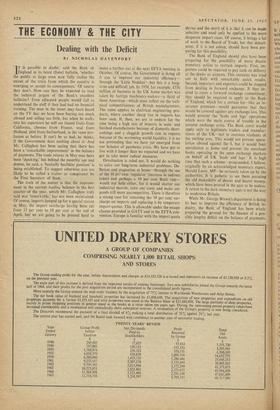

It retains the $750 million swap arrangement with the Federal Reserve and the $250 million credit line with the US Export-Import Bank. Whether Mr. Callaghan can enlarge these credits when he goes to sec the new Secretary of the American Treasury, Mr. Henry Fowler, at the end of the month remains to be seen. (I am assuming that his recent conversation in London with M. Giscard .d'Estaing brought no rabbit out of the gold hat now worn by President de Gaulle.) To these certain American credits of $1,000 million must be added our 'second line' reserve of $1,250 million represented by the Government's portfolio of dollar securities which the Bank has recently been turning into the more liquid form of US Treasury bonds. (Did its sell- ing start the recent Wall Street slump?) Finally, there arc the official gold and convertible cur- rency reserves which the Bank brought up to £1,021 million last month by crediting the balance of $343 million (£122 million) left over from the IMF loan after paying off the central bank credits used in the exchange crisis. It may be objected that £900 million of these £1,021 million reserves are pledged for the repayment of $2,400 million now borrowed from the IMF and $120 million from Switzerland, but these loans range up to five years, so that the Bank has immedi- ately available over $5,000 million for the finance of a continuing, but diminishing, deficit. In all conscience this should be more than enough— even if the combined deficit on trade and capital account this year falls to only £300 million. (In

view of the expected cut in private investment overseas and—we hope—in government defence spending overseas, the deficit should certainly not exceed that figure.) For the Observer to run a tendentious article entitled 'Can we stop Britain going broke?' was therefore singularly inept. Our government finances remain strong: our private wealth immense.

Previous page

Previous page