Tank-trap flower-beds

Gavin Stamp THE streets of London may never have been paved with gold but at least they were properly paved. Granite kerb stones di- vided road surfaces of wood blocks or granite sets from the pavements laid with slabs of York stone, whose natural beauty was enhanced, in the Georgian parts of the city, by the insistent rhythm of cast-iron coal hole covers. Such surfaces required maintenance, of course, but they were as practical as they were unobtrusively ele- gant.

Today the elegance has departed along with the practicality. The streets of the London Borough of Camden, in which I as well as The Spectator have the misfortune to reside, are filthy, hideous and danger- ous. Not only are the roads full of holes and incompetent repairs, the pavements are undulating plains of concrete slabs, badly repaired with cement or tar and further textured by the bits of equipment scattered around by the Gas Board and British Telecom. Such streets are some- times impassable for the pushchair and physically dangerous for the disadvantaged groups in society that the council affects to be so concerned about; the result is pain- fully hideous and unharmonious to anyone with an eye. And then there is all the junk: the serried ranks of parking meters, badly positioned tall lamp-posts, endless notices, the artful creations of road engineers and, often, completely gratuitous poles that bear only tiny notices concerning parking restrictions that would be best affixed elsewhere. Our streets are no longer for the pedestrian, affording an unhurried contemplation of architecture; they are now the property of the insistent, arrogant, blind motorist. It is deplorable.

The replacement of Sir Giles Scott's carefully-designed and beautifully prop- ortioned solid cast-iron telephone kiosks by British Telecom's cheap, tawdry Manhattan-style booths is merely symp- tomatic of a much wider cultural decline. Our streets are now a reflection of our vulgar, meretricious, asset-stripping cul- ture. Tough, durable, sound materials stone, granite, cast-iron — are replaced by cheap, impermanent ones — sheet metal, concrete and plastic. Good materials are usually more practical: as our roads seem to be dug up every other week, how much better it would be if we still had cobbles, as do many European cities. But the motorist rules, and he likes tarmac.

Apart from the question of maintenance and repair, the hideousness of our streets seems to have little to do with politics. There is as much designer-junk in Lady Porter's Westminster as there is in the People's Republic of Camden. A prime example of the visual anarchy that now reigns is Oxford Street. From Tottenham Court Road to Marble Arch, the pave- ments are obstructed by notices, garish plastic litter bins that are as offensive as what they contain, advertising displays, and a cacophony of new telephone boxes while the kerb undulates in and out, with `nibs' filled with tarmac or cement, according to the whim of traffic managers. The authority and discipline — so neces- sary for real freedom — once imposed on streets by the careful work of the local vestry or even London Transport has now gone.

It might be supposed that as so much street furniture is comparatively ephemeral in nature, what is flimsy and temporary in character might be least noticeable. The exact reverse seems to be the case. The least obtrusive street furniture is that which is solid and designed with an eye to appearance as well as durability. In such things can one take real pleasure, for thought has gone into them: railings, lamp- posts, pillar-boxes, bollards. Bollards are particularly interesting as the design of what is simply a solid obstruction has evolved subtly over several centuries. The earliest examples are simply up-ended cannon with a ball rammed in the muzzle — but as even instruments of destruction were once carefully modelled with mould- ings, such things are elegant and interest- ing. The Regency, typically, evolved new models, like the rectilinear uprights with chamfered edges and horizontal, Soanian fluting which, bearing the monogram of William IV, protect Charles I at the top of Whitehall. And while in Trafalgar Square, it is worth looking at the massive round

LONDON SPECIAL

granite bollards placed by Sir Charles Barry on the upper terrace: solid, satis- fying objects with the tough, heroic quality of nautical design. How different is the modern bollard — an object as necessary as ever to protect the vulnerable pedestrian from vehicles — just an ugly tapering cylinder of reinforced concrete that shat- ters at the first biff.

The same evolution, ending with bathe- tic collapse, can be seen in the design of railings and lamp-posts — how beautiful, again, are those William IV lamps in Constitution Hill — and even in those comparatively modern utilities like tele- phone kiosks and pillar boxes. Pillar boxes, indeed, were a model of urban civilisation, as they had to be very tough and were carefully fashioned in the manner of a classical column — fluted Doric in the earliest surviving examples. Now the bar- baric Post Office, which, under the thrall of the marketing men, has replaced the authoritative Trajan lettering appropriate to a national institution with designer plastic, actually proposes to clip on plastic boxes to the cast-iron pillars to cope with the flood of junk mail. That sense of true public responsibility has gone.

What is depressing is how quick and deep the collapse has been, for high standards in the design of street furniture were consciously striven for early this century. Architects were actively in- terested in producing good civic art. The decade that saw the advent of Scott's kiosks — the 1920s — also saw the founda- tion of the Royal Fine Art Commission, intended to improve visual standards in the public realm, as well as the superb work commissioned by Frank Pick for the Underground. Even after the second world war, Sir Albert Richardson — who had fought hard to save railings from pointless seizure, that great scandal of the war attempted to tame the disruptive innova- tion of neon and sodium street lighting by designing his thin, fluted Roman candle lamp-standards for cities like Cambridge. Typically, these are now being removed by the city council.

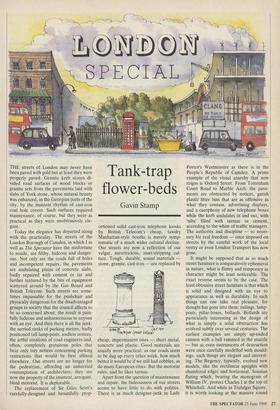

But even worse than the slovenly pro- digality of local authorities are their posi- tive attempts at urban improvement. If a shopping street is pedestrianised, rather than simply erecting a row of bollards, the whole area has to be repaved — usually in coloured concrete — while the space is filled with idiotic, redundant flower tubs. This negates truly urban character, which is solid and austere. To add insult to the injury caused by its neglect of pavements, Camden Council now spoils street corners with textured ramps of pink cement. Characteristic is the treatment of Montagu Place, the street running between Bedford

and Russell Squares, which is framed by grand classical buildings of Portland stone: Burnet's King Edward VII Galleries of the BM facing Holden's London University. At colossal expense, Camden has chosen to enhance this civic dignity by erecting tank-trap flower-beds of pink bricks in the middle of the street. Can nobody see any more?

THESE INCONGRVOVS LAMP POSTS WHICH DETRACT FROM THE BEAVTY OF THIS HISTORIC TOWN WERE ERECTED BY THE VRBAN DISTRICT COVNCIL AGAINST THE ADVICE OF THE ROYAL FINE ART COMMISSION. So ran the notice raised in Ampthill by Sir Albert Richardson at the end of his unsuc- cessful campaign to prevent the erection of 15-foot-high pregnant penguins COUT OF SPITE AND IGNORANCE' was painted out by the advice of the family lawyer). But there is no shaming a bureaucrat. These days the council erects its own, superfluous and tautological notice to announce an ENVIRONMENTAL AREA which it has done its best to disfigure with concrete bol- lards, coloured paving, cement 'nibs' pro- jecting into the road and ungainly lamp standards while having failed to prevent British Telecom and the Post Office from taking away what once gave real pleasure. To enjoy London streets one must now look at old photographs.

Previous page

Previous page