Ballet

The Time-Machine

By CLIVE BARNES school outside of Russia that could even physically undertake the venture. Whatever its opponents may say of the Royal Ballet School, it is efficient—and huge.

Five of the leading roles were danced by very junior members of the company itself, but all the other parts were given by no fewer than 127 students. Carefully rehearsed by Peggy Van Praagh and following the standard Covent Garden version with .the precise mimicry of a carbon copy, the casual ballet-goer wandering into the Opera House last Saturday might pos- sibly not have noticed much difference between this performance and one by the main company, or even if he did notice it he would possibly find it quite difficult to pin down that difference accurately. Yet there were revealing discrepan- cies, that of innocence and experience, that of terrier-puppy fervour and controlled, greyhound enthusiasm. About the students, comparativelY few of whom will ever graduate to one of the Royal Ballet Companies, there was a discernible gawkiness to their adolescent physiques and equally a fuzziness to their dance technique. Countering this was their innocence, the pleasure , they got and gave from doing something difficult for the first time, the communication of that sense of occasion and ceremony that their more sophisticated and blasd elders have inevitably lost.

These student performances are useful in showing the work done by a vast section of the Royal Ballet organisation which would other- wise be virtually hidden; they also in part act as time-machines into the company's future, show- ing the dancers at present emerging from the system. The conventional criticism of this system's teaching standards is that it knocks out a dancer's individuality and enforces conformity to a given style and manner. That such criticism is, in a very limited sense, basically true must be evident from the ensemble in both student and company performances; that it is justified as criticism seems questionable. What represents mediocre conformity to a disappointed dance teacher, dejected soloist or rejected student, Dame Ninette de Valois can claim as companY discipline and the homogeneous style all national ballets perspire to attain. A school is like a government in that it must be judged by results. When iny colleague David Cairns was writing about the musical 'academies recently, he made it, to my view, game, set and match by unanswer- ably questioning how many artists those institu- tions had produced. The Royal Ballet School has the answer to that ruthlessly fair question dancing at Covent Garden; the proof of their recipe is to be found in the international reptAta- tion of their cuisine.

The Royal Ballet School, like any human foundation, has its faults--yes, it does chase ton relentlessly and dogmatically the myth of a purely 'English' style as opposed to the 'Russo Italian' style it in fact possesses; yes, its graduates do seem even more shamefully ignorant of ballet history than their musical counterparts are of music history; yes, the boy-scout. sign-language mime taught at the schodl is a ludicrously inade- quate means of theatrical communication—but, but, but, look merely at the three dancers who led this school performance of Swan Lake. Georgina Parkinson's vibrant, highly strung Odette, some- what short on facial expression and musical feel- ing yet rich in the eloquence of her movement, contrasted well with Shirley Grahame's male- volent, crisply danced Odile. Even better than either was Bryan Lawrence's confidently asser- tive Prince Siegfried, blending athletic dancing with just that boyish romanticism that can—and in Siegfried's case does—lead to an early suicide.

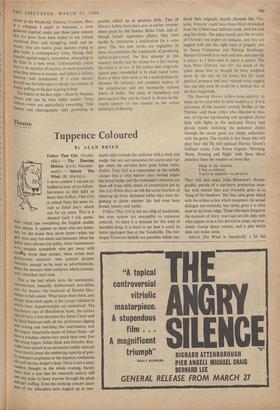

All in all last week was a sort of national youth festival in the ballet theatre, for not only was there this students' Swan Lake, but there was also a new company—Norman Dixon's 'Ballet Venture —1960'—starting a season of ballet-in-the- round at the Pembroke Theatre, Croydon. Here Is a company I ought to welcome, a crew gathered together under just those same colours that for years have been nailed to my critical masthead. Poor and struggling, weak and in- secure, they are twelve good dancers trying to give ballet a contemporary voice, flexing their muscles against sugary convention, attempting to flY kites in a new wind. Unfortunately critics have to be apostles of success, or more accurately What they believe is success, and failure is failure, however well intentioned. If a critic doesn't himself see the kites take to the air, no amount of kindly puffing on his part is going to help. The ballets on the first night—three by Norman Dixon and one by their ballet master, Terry Gilbert—were not particularly rewarding. Trite themes and choreography only promising in patches added up to precious little. Two of Dixon's ballets have been seen in earlier versions when given by the Sunday Ballet Club, and al- though honest apprentice efforts, they were hardly by themselves a justification for a com- pany. The two new works are negligible. In these circumstances the experiment of producing ballet-in-the-round, the first attempt in this country, hardly had the chance for a fair testing, the more so as two of the ballets were originally square pegs remodelled to fit their round holes. Even so there does seem to be a marked disparity between the intimacy and potential realism of the presentation and the necessarily stylised fabric of ballet. The sense of immediacy and participation that can be found in drama-in-the- round appears to run counter to the actual technique of dancing.

Previous page

Previous page