FLEET STREET GOES TO THE DOGS

National newspapers face their greatest premises may not change the printers

A LINE of urine ran like a tiny brook down the slope of the alley towards Fleet Street. A second later its author appeared, still buttoning his fly, red-faced, staggering and very, very drunk. Not a particularly unusual sight — just a national newspaper Printer worker returning from lunch. But for me it was a life class example of what a senior executive on one of the national newspapers had just been telling me: that compared to the labour he had had to deal with in other industries, Fleet Street work- ers are of a poorer standard, with drunken- ness high on a list of problems, a list which includes absenteeism, lack of discipline and a complete absence of any sense of commitment to company or product.

Perhaps the generalisation was too broad. There are plenty of printers still continuing the tradition of working-class erudition, others who do not hang about in Fleet Street pubs but fly straight as arrows to their elegant homes in the suburbs, as keen to get in a round of golf before commuting back to the City as any com- pany director.

The plain fact is that any long-term resident of Fleet Street knows that despite the proverbially heavy drinking it is one Part of London where the number of pubs has actually declined. Nor do those that remain cater exclusively for print workers: Journalists, too, have been known to re- turn from lunch the worse for wear.

Nevertheless, the drop in the number of watering holes is bound to intensify as Fleet Street is overtaken by the biggest change it has experienced since the rotary Press was invented. For the newspapers, stuffed with money from the Reuters flota- tion and experiencing one of their periodic upswings, are moving their printing and Publishing operations into new purpose- built plants in dockland.

Not all the papers are going: Times Newpapers, the Mirror Group, the Finan-

cial Times and the Express are staying put: all of them have comparatively modern Machinery which can be upgraded, and the latter pair, the object of takeover rumours, Would be weakened by the outlays in- volved — perhaps as much as £100 million for each paper. (It isn't entirely clear whether Robert Maxwell's sudden im- pulse, announced this week, to move the Mirror's printing to dockland is part of his continuing war of nerves against the un- ions, another move to consolidate his BPCC empire, or just one more Maxwell gimmick.)

The Guardian is the only paper compel- led to make the move. Its contract with Times Newspapers, who print the Guar- dian on three of their presses in Gray's Inn Road, expires in 1988 and will not be renewed. In keeping with the paper's currently poor financial position, it is the

only one doing the move to dockland on the cheap. It has purchased a small site still empty when I peered through the chain-link fence the other day — where three new and faster German presses will be installed, at an overall cost of £15 million. The journalists and the composi- tors will remain at the Farringdon Road offices, the leasehold on which was recent- ly purchased for just over four million pounds.

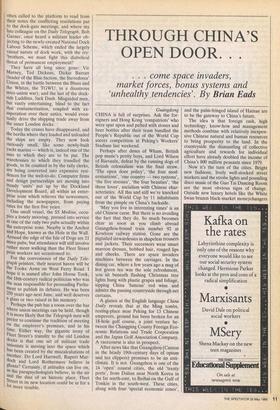

The Daily Telegraph, which appears to be in gentle decline yet still manages to sell more papers than the Times, the Guardian and the FT combined, has more grandiose plans. Close to the empty Guardian site on the Isle of Dogs a high-tech building which could be an oil refinery is nearing comple- tion on a 12-acre site in West Ferry Road: the southern print run of the Daily Tele- graph and the entire printing of the Sunday Telegraph will take place here. Assuming negotiations with the print unions stay on course, the move from Fleet Street will be made in stages from the end of next year when four new Goss Headliner presses should be installed, with two or more to follow in February 1987 and a final pair three months later.

The presses themselves help to explain why the Telegraph is deserting all but the façade and front section of its building in Fleet Street as though it were an accursed place. Behind those Mussolini-esque col- umns, with the frieze over the bronze doors depicting, as Colin Welch pointed out to me many years ago, two winged messengers hurrying in opposite directions with their ankles tied together, there are 14 rotary presses.

Five were installed in 1928 when the first Lord Camrose bought the Telegraph from the Lawson family. The remaining nine were purchased in 1937, but a union dispute Icept two of these in mothballs until the late 1960s. So while these might still have some value to a Third World pub- lisher because of their comparitively low mileage, the fact remains that the Tele- graph is currently printed on machines of considerable antiquity.

The surroundings of the Telegraph machine room are grim to an extreme; distressingly noisy, cramped and dark, rather like the engine room of a Titanic where the sailors never bothered to clean the brasswork or repaint the steel girders. The machines each spew out 24,000 papers an hour: the Headliners at the Isle of Dogs plant, in light and airy surroundings, will have a speed of 60,000 an hour.

Rupert Murdoch's News Group are also heading for dockland, where they intend to print the Sun and the News of the World.

Their Tower Hamlets plant is almost ready for occupation., but industrial disputes in Fleet Street are delaying the move. It is difficult to analyse the industrial relations problems being experienced at the Sun and

the News of the World except, again, in terms of history. What seems to be hap- pening is that the National Graphical Association (NGA) is trying to use the transfer of the printing operation from Fleet Street as an opportunity to redress an ancient grievance. A strike by one of its predecessor unions (Fleet Street print un- ions have rationalised themselves by mer- gers to a degree unusual in many other industries) back in the 1920s led to mem- bers of a less-skilled union, which has now resolved itself into the Society of Graphical and Allied Trades (Sogat), holding all the day shift jobs in the machine room, and 50 per cent of the night shift as well. In other papers it is the NGA which is dominant; the union's solution here involves an in- crease in the number of machine room jobs at the new plant, despite the fact that the new technology demands far fewer, an idea which must delight the ghosts of Asquith and Lloyd George.

At any rate, News Group management, after two years of frustrated negotiation over manning levels at the new plant, have now suspended the talks, claiming that the unions are ready, to go to Tower Hamlets 'only on their own terms'. A side issue, but no doubt equally aggravating, concerns the publishing room — the handling and pack- aging of the papers off the presses and their loading into vans — where 350 'casuals', a strange Fleet Street half-world which be- came famous in the 'Mickey Mouse' tax- free wages scandal a few years ago, are employed each night. News Group, wishing to take advantage of the highly mechanised handling equipment installed at Tower Hamlets, want to cut this number down to 57 once the move is made. Unless there has been some kind of revolution in management attitudes overnight, it is a fair bet that the number of casuals in the publishing room at Tower Hamlets will be closer to the present Fleet Street number than to the magic Heinz figure.

Unlike the Telegraph, the Sun or the Guardian, Associated Newspapers, pub- lishers of the Daily Mail, the Mail on Sunday and half the London Standard, is playing the whole docklands game far more cautiously: so cautiously, in fact, that it could get left behind in the technological race. For while their rivals have decided to negotiate with the unions while the move to docklands is imminent, Associated Newspapers are bluffing it out in an attempt to secure the manning levels they want before they finally commit them- selves to a move to a still empty site in the old Surrey docks.

Lord Rothermere has, in effect, told the unions: before we make a large investment in the papers' future, you must show that you are willing to make an investment, too.

So the Mail newspapers want agreement on lower manning levels and voluntary

redundancies before they will go ahead.

This could leave them without one impor- tant dimension which will be available from the modern presses now being instal- led in dockland: colour. Existing technol-

ogy allows pre-printed colour for advertise- ments or occasional set-piece news or feature stories, but the new machinery will enable colour pictures and advertisements to appear as a matter of course. Since this will be one of the main selling points of Eddie Shah's new daily paper, and what- ever happens with the unions the Mail group do not intend moving out to the docks before 1990, they would seem to be placing themselves at a serious disadvan- tage.

What all Fleet Street managements want, of course, is realistic manning levels. The move to the docks is a heaven-sent opportunity to achieve it, particularly when the threat from Eddie Shah and the proposed new down-market tabloid back-

ed by Irish interests, together with Mur- doch's new evening Post and the possible new Sunday from ex-Mirror chief and building society manager Clive Thornton, are all threatening a new era of unaccus- tomed outside competition.

Union policy, as interpreted in the boardrooms, is that they will only agree to lower manning if the reductions are cou- pled with the introduction of new technolo- gy. That would seem to apply to the dockland operations but no doubt the papers which are staying put will wish to piggy-back reductions in staff for them- selves if and when their rivals make their new deals.

And as always in Fleet Street, it is a question of price. The Telegraph group appears to be closest to a settlement of the question of buying-out the piecework agreements which make compositors the highest-paid workers in Britain. It is not, however, simply a question of how much they are paid: the London Scale of Prices, by which the piecework rates are deter- mined and which goes back far beyond even the antique machinery currently used for typesetting, is so complex that hardly anyone in management understands it. That means that the payments system is unpredictable and virtually uncontrollable.

Not even the Telegraph has reached a final agreement yet, but the principle,

which will guide all the papers, is a willingness on the part of management to abolish the London Scale by buying it out.

The idea is to set a fixed wage (probably around £500 a week) and then to deter- mine how much each compositor would have earned under the old system. The difference between the two would bd paid out in a series of lump sums over three years. Current estimates are that they will each receive something in the region of £40,000 — perhaps rather more — for selling their piecework rights.

Alongside this exercise, which applies only to pieceworkers, the papers are anx- ious to encourage voluntary redundancies. Present arrangements have acted as a positive deterrent to retirement: with no fixed retirement age, print workers have carried on gallantly into their eighties rather than accept the 47p per week for each year of service which is all the Telegraph's non-contributory pension scheme offers them as a reward for long service.

A new redundancy scheme offering four weeks' pay for each year of service, with a maximum of £400 in defining a week's pay, will soon be on offer. So, for a printer with 25 years' service, a maximum of £28,000 as a final pay-off will be available, though management realists admit that this is probably still too low to secure the num- bers of redundancies they wish to achieve. Some fortunate individuals, apparently, will be able to qualify for both the piece- work buy-out and the redundancy scheme, thus creating, one might think, the next generation of nouveaux riches whose scions might wish to become press barons.

But it is not the minutiae of compensa- tion, nor even the impact on Fleet Street's social habits of the forthcoming exodus which excites the imagination. The thrill comes from a realisation of where they are going.

Thirty years ago it was often my grim duty to rise at an unearthly hour in the morning to get myself to the dock gates to report on the mass meetings which decided on the most dubious count of hands and heads to stage the unofficial strikes which eventually were to spell the end of the East London docklands.

Against a background of idle cranes, and with public houses permitted to open before most people's breakfast time, the dockland militants held sway, able and eager to defy union leaders like Arthur Deakin, beside whom today's leaders of the Transport Union look like cissies. Deakin, and the Transport & General Workers' Union of his day, was even less mindful of the niceties of democratic bal- lots. He personally seldom ventured into the docks, and when he did so it was in a heavy Ford V8 Pilot motor-car weighing a ton and a half, thus defying the efforts of his disaffected members to overturn 't.

Few of his immediate successors, including Frank Cousins, went near the London docks at all.

It was in this setting that reporters were often called to the platform to read from their notes the conflicting resolutions put to the dock-gate meetings, and where my late colleague on the Daily Telegraph, Bob Garner, once heard a militant leader ob- jecting to the newly-created National Dock Labour Scheme, which ended the largely casual nature of dock work, with the cry: 'brothers, we must fight this diabolical threat of permanent employment!'

They have all long since gone: Vic Marney, Ted Dickens, Dickie Barratt (leader of the Blue faction, the Stevedores' Union, in the battle between the Blues and the Whites, the TGWU, in a disastrous inter-union war), and the last of the dock- side Luddites, Jack Dash. Misguided men, but vastly entertaining, blind to the fact that containerisation, coupled with ex- asperation over their antics, would even- tually drive the shipping trade away from the inner London docks.

Today the cranes have disappeared, and the berths where they loaded and unloaded the ships are empty. They now look curiously small, like some newly-built Yacht marina — which is, indeed one of the uses to which they are to be put. The Warehouses to which they trundled the goods, to be counted in by the tally clerks, are being converted into expensive resi- dences for the well-to-do. Computer firms and design partnerships are moving into trendy 'units' put up by the Dockland Development Board, all within an enter- prise zone which relieves the newcomers, including the newspapers, from paying rates for the first five years.

One small vessel, the SS Medina, occu- pies a lonely mooring, pressed into service as one of the only two pubs actually within the enterprise zone. Nearby is the Anchor and Hope, known as the Hole in the Wall. Around the edge of the Isle of Dogs are 21 more pubs, but attendance will still involve rather more walking than the Fleet Street print workers are accustomed to.

For the convenience of the Daily Tele-• graph printers, their nearest haven will be the Tooke Arms on West Ferry Road. I hope it is named after John Home Took, the 18th-century radical politician who was the man responsible for persuading Parlia- ment to publish its debates. He was born 250 years ago next June, and well deserves a glass or two raised in his memory. Perhaps the pub has a room over the bar Where union meetings can be held, though it Is more likely that the Telegraph men will Prefer to continue the tradition of meeting On the employer's premises, and in his time. Either way, the gigantic irony of Fleet Street's transfer to the old London docks is that one set of militant trade unionists is moving into the space which has been created by the miscalculations of another. Do Lord Hartwell, Rupert Mur- doch and Lord Rothermere believe in ghosts? Certainly, if attitudes can live on, as the parapsychologists believe, in the air and the dust of an historic place, Fleet Street in its new location could be in for a lot more trouble.

Previous page

Previous page