THROUGH CHINA'S OPEN DOOR..

. . . come space invaders, market forces, bonus systems and

'unhealthy tendencies'. By Brian Eads

Guangdong CHINA is full of surprises. Ask the for- eigners and Hong Kong 'compatriots' who were spat upon and pelted with stones and beer bottles after their team bundled the People's Republic out of the World Cup soccer competition at Peking's Workers' Stadium last weekend.

Perhaps after doses of Wham, British pop music's pretty boys, and Lord Wilson of Rievaulx, defeat by the running dogs of British colonialism was the final straw. 'The open door policy', 'the four mod- ernisations', 'one country — two systems', 'the five stresses', 'the four beauties', 'the three loves', socialism with Chinese char- acteristics. All this and still we're knocked out of the World Cup by 11 inhabitants from the pimple on China's backside.

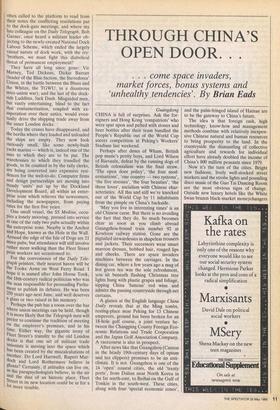

'May you live in interesting times' is an old Chinese curse. But there is no avoiding the fact that they do. So much becomes clear as soon as you climb abroad Guangzhou-bound train number 92 at Kowloon railway station. Gone are the pigtailed stewardesses in shapeless trousers and jackets. Their successors wear smart maroon dresses, bobbed hair, rouged lips and cheeks. There are space invaders machines between the carriages. In the dining car, where a few years ago a mug of hot green tea was the sole refreshment, you sit beneath flashing Christmas tree lights hung with plastic grapes and foliage, sipping China 'famous' red wine and admire the passing countryside through net curtains.

A glance at the English language China Daily reveals that at the Ming tombs, resting-place near Peking for 13 Chinese emperors, ground has been broken for an 18-hole golf course, a joint venture be- tween the Changping County Foreign Eco- nomic Relations and Trade Corporation and the Japan Golf Association Company. A racecourse is also in prospect.

After news like that Guangzhou (Canton in the heady 19th-century days of opium and tea clippers) promises to be an anti- climax. It is not. Guangzhou is one of the 14 'open' coastal cities, the old 'treaty ports', from Dalian near North Korea in the far north-east, to Beihai on the Gulf of Tonkin in the south-west. These cities, along with four 'special economic zones', and the palm-fringed island of Hainan are to be the gateway to China's future.

The idea is that foreign cash, high technology, know-how and management methods combine with relatively inexpen- sive Chinese natural and human resources to bring prosperity to the land. In the countryside the dismantling of collective agriculture and rewards for individual effort have already doubled the income of China's 800 million peasants since 1979.

Now it's the turn of the cities. Bright new fashions, lively well-stocked street markets and the strobe lights and pounding disco music of the Guo Tai Dancing Room are the most obvious signs of change. Outside new luxury hotels like the White Swan brazen black-market moneychangers

speak eloquently of a new era. The over- crowded, dilapidated buildings, the snak- ing queues for charcoal cooking fuel and subsidised rice and noodles, are equally eloquent signs of just how far there is to go. China's per capita annual income is under US$350.

A visit to the bi-annual export commod- ities fair is instructive. About one quarter of China's foreign trade is conducted there. There are bulldozers and Xinjiang silk rugs, ginseng and textiles, machine tools and rattan furniture, a replica of the M-16 assault rifle and 'China's secret weapon' a pingpong training machine that fires 90 balls a minute. Yours for US$3,000. A great deal of business was done, though probably less than the US$2.4 billion last year. But as the organisers are the first to admit, •unreliable quality, lack of flexibility in production, shortcomings in delivery and packaging are all major problems.

Guangzhou officials believe visiting managers from what is now known as 'inland China' are learning valuable lessons from its management reforms. Guangzhou in turn is expected to learn its lessons from Shen Zhen, the oldest, biggest and richest of the four special economic zones.

Five years ago Shen Zhen was a sleepy agricultural community of 30,000 people close enough to Hong Kong to pick up its television programmes and watch the neon light up its night sky. In most other respects it might have been on another planet. Now it has 400,000 people, sky- scrapers of its own and about half of the four billion American dollars of foreign investment that have gone into China. You could be mistaken for thinking you were in a new town in Hong Kong's new terri- tories.

The local slogan, endorsed by Party leader Deng Xiaoping, is 'time is money. efficiency is life'. Here, officials were keen to point out, the 'iron rice bowl' had been smashed. In 'inland China' the lazy worker eats as much as his industrious brother. Here more work meant more pay. They have clocking in, quality control, bonus systems, market forces, all learned from foreign capitalists to lay the basis for replacing 'outmoded economic structures'.

Among the joys the modernising process has brought is the Happiness Soft Drink Factory, which last year produced two- and-a-half million cases of Pepsi-Cola. The Honey Lake Country Club, with big dipper and speed boat rides, and access to casset- tes of romantic Cantonese ballads from across the border — `so much more tender than those boring marching songs', as one young man observed.

The plans for Shen Zhen are ambitious. Many of them have been realised, and there are hundreds of joint-venture pro- jects with foreign firms under way. The cardboard and plastic model in the Plan- ning Department, a vision of the year 2000, has an international airport, a four-land highway to Guangzhou, a nuclear power plant (with a significant British input from General Electric), playing fields, pastel pink and green apartment blocks, Spanish- style villas for returning 'compatriots', sprawling industrial zones, theatres, sports fields and amusement areas. Interestingly, among the projects that have been com- pleted at breakneck speed is an 80- kilometre fence separating Shen Zhen 'I see they are becoming civilised at last.' from the rest of Guangdong province.

The fact is that China sees the economic benefits of an 'open door', but is fearful of the wider consequences. Smuggling of duty-free goods is already one of them and not a few transgressors have been ex- ecuted, including the Party secretary of the coastal county. There are people who would argue that already China has gone too far, too fast.

The economy is overheating after an unprecedented spending binge on consum- er goods. There is confusion about the exact mix of central and local control. There is widespread official corruption, known as 'unhealthy tendencies'. Por- nography and other 'spiritual pollution' has slipped through the 'open door', and the crackdowns and abrupt shifts in regulations governing taxation and contracts have un- nerved many foreign investors.

For many, especially Hong Kong and overseas Chinese, investments in China have been more political insurance than economic good sense. There is less enthu- siasm for the exercise now. The carpetbag- gers hoping to make a quick fortune from the world's largest market are finding that China is not to be plundered as in the past. British companies, hoping for an inside track thanks to the Hong Kong accord, may turn out to be among the dis- appointed.

For Deng Xiaoping is, of course, balanc- ing on a difficult tightrope. He is at pains to point out that the death of Marxism in China has been much exaggerated: disco dancing, killjoy comrades are assured, is just physical jerks to music. His most dangerous enemies are the 'whateverists', the diehard Maoists clinging desperately to their power and beliefs. It is a long, difficult and dangerous business to replace them with younger, reform-minded men. At the same time he must root out the idle and the corrupt without alarming the West. The execution of some 10,000 criminals in the past 18 months raised many eyebrows.

And, perhaps most worrying for Peking, he must enable the fulfilment of rising expectations evenly throughout Chinese society without letting go the ComMunist Party's grip on the levers of power. No Little Red Book has yet been written to guide the Chinese leadership down the path they have chosen. It is all trial and error: towards the goal of quadrupling national income by the end of the century. In pioneering Shen Zhen one 30-year-old man laughed as he re- minisced about waving Mao's Little Red Book and chanting the late Chairman's thoughts, then grew sombre as he recalled his father's being dragged away to 're- education'. Yes, he approved of disco and washing machines and television sets and refridgerators. The people, he said, loved Comrade Xiaoping: he had made them rich. There was no nostalgia for Mao. What if 81-year-old Xiaoping was to die? 'The leaders say don't worry', he said, 'the people also love the new policies, and the people are strong.'

Previous page

Previous page