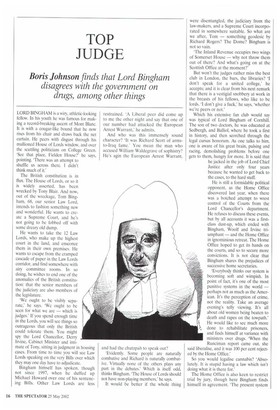

TOP JUDGE

Boris Johnson finds that Lord Bingham

disagrees with the government on drugs, among other things

LORD BINGHAM is a wiry, athletic-looking fellow. In his youth he was famous for making a record-breaking ascent of Mont Blanc. It is with a cougar-like bound that he now rises from his chair and draws back the net curtain. He peers with disgust through his mullioned House of Lords window, and over the scuttling politicians on College Green. 'See that place, Fielden House?' he says, pointing. 'There was an attempt to shuffle us across there. I didn't think much of it.'

The British constitution is in flux. The House of Lords, or so it is widely asserted, has been wrecked by Tony Blair. And now, out of the wreckage, Tom Bingham, 68, our senior Law Lord, intends to fashion something new and wonderful. He wants to create a Supreme Court, and he's not going to be fobbed off with some dreary old dump.

He wants to take the 12 Law Lords, who make up the highest court in the land, and ensconce them in their own premises. He wants to escape from the cramped cascade of paper in the Law Lords corridor, and find somewhere with airy committee rooms. In so doing, he wishes to end one of the anomalies of the British constitution: that the senior members of the judiciary are also members of the legislature.

'We ought to be visibly separate,' he says. 'We ought to be seen for what we are — which is judges.' If you spend enough time in the Lords, you will see things so outrageous that only the British could tolerate them. You might spy the Lord Chancellor, Derry Irvine, Cabinet Minister and intimate of Tony, sitting in judgment in housing cases. From time to time you will see Law Lords speaking on the very Bills over which they may one day have to adjudicate.

Bingham himself has spoken, though not since 1997, when he duffed up Michael Howard over one of his sentencing Bills. Other Law Lords are less restrained. 'A Liberal peer did come up to me the other night and say that one of our number had attacked the European Arrest Warrant,' he admits.

And who was this immensely sound character? 'It was Richard Scott of armsto-Iraq fame.' You mean the man who accused William Waldegrave of sophistry? He's agin the European Arrest Warrant, and had the chutzpah to speak out?

'Evidently. Some people are naturally combative and Richard is naturally combative. Virtually none of the others plays any part in the debates.' Which is itself odd, thinks Bingham. 'The House of Lords should not have non-playing members,' he says.

It would be better if the whole thing were disentangled, the judiciary from the law-makers, and a Supreme Court incorporated in somewhere suitable. So what are we after, Tom — something geodesic by Richard Rogers? The Dome? Bingham is not so vain.

'The Inland Revenue occupies two wings of Somerset House — why not throw them out of there? And what's going on at the Scottish Office at the moment?'

But won't the judges rather miss the best club in London, the bars, the libraries? 'I don't speak for a united college,' he accepts; and it is clear from his next remark that there is a vestigial snobbery at work in the breasts of his fellows, who like to be lords. 'I don't give a fuck,' he says, 'whether we're peers or not.'

Which his extensive fan club would say was typical of Lord Bingham of Cornhill. The son of two doctors, he was educated at Sedbergh, and Balliol, where he took a first in history, and then scorched through the legal cursus honorum. As one talks to him, one is aware of his great brain, pulsing and racing, demolishing problems before one gets to them, hungry for more. It is said that he jacked in the job of Lord Chief Justice after only four years because he wanted to get back to the cases, to the hard stuff.

He is still a formidable political opponent, as the Home Office discovered last year, when there was a botched attempt to wrest control of the Courts from the Lord Chancellor's department. He refuses to discuss these events, but by all accounts it was a firstclass dust-up, which ended with Bingham, Woolf and Irvine triumphant — and the Home Office in ignominious retreat. The Home Office hoped to get its hands on the courts, and so to secure more convictions. It is not clear that Bingham shares the prejudices of successive home secretaries.

'Everybody thinks our system is becoming soft and wimpish. In point of fact, it's one of the most punitive systems in the world — perhaps not as much as the American. It's the perception of crime, not the reality. Take an average evening's telly viewing. It's all about old women being beaten to death and rapes on the towpath.' He would like to see much more done to rehabilitate prisoners, and finds himself at variance with ministers over drugs. 'When the Runciman report came out, she said liberalise, and it was 100 per cent rejected by the Home Office.'

So you would legalise cannabis? 'Absolutely. It is stupid having a law which isn't doing what it is there for.'

The Home Office is also keen to restrict trial by jury, though here Bingham finds himself in agreement. 'The present system did not cause injustice, but there are compelling reasons — of expense and so on — for a change. When I was Lord Chief Justice I went to Liverpool and tried a man who had 60 previous convictions for shoplifting. He called for a jury trial and, at a considerable expense to the taxpayer, it had to be decided whether or not he had taken bacon off the shelf. Of course he was convicted.'

In 1995 I wrote a piece in this magazine denouncing judicial activism, and the tendency of judges such as Bingham to usurp the role of elected politicians. He then came up to me at some party, and said the article had made him very cross. He does not believe that the judges are getting too big for their boots, though he does think that Westminster is losing out to Brussels. 'It is inevitable that the parliament of a member state of a larger entity will lose power and authority as that entity gets more dominant.' he says.

'People have got a perfectly clear idea that the Queen in Parliament is ruling them, but they understand with varying degrees of satisfaction that there has been a ceding of powers.' Bingham himself has found himself corrected by a European institution, in the judgment he made over gays in the military. He said it was OK to ban them; Strasbourg said it wasn't.

But he is a generous. far-sighted, liberal kind of a Balliol man; and he believes in innovations such as the International Criminal Court. It's quite wrong of the Americans to boycott the institution, he says. 'You've got to take that risk. You've got to trust people. I'm in favour of it, for rather the reasons I took a minority view on General Pinochet, because if people have committed crimes against the international community or world peace, it's highly desirable that they should be tried by an international court.' He thought it wrong that Pinochet should be tried in Spain, but he thought he should be tried.

He once fought an action against Pinochet on behalf of Cuba. It was all about some sugar that Fidel Castro tried to sell to Salvador Allende, his brother-inarms, on the eve of the coup. When Pinochet took over, Castro ordered the sugar boats to turn back. One of them did, even though the Chileans had paid for the sugar, and the question was whether the Chileans had the right to distrain a Cuban vessel in Tyneside.

As he goes on, it beats me how he can remember it all so clearly. What a mind. One thing he has forgotten is an early brush with another ambitious lawyer. 'Blair tells me that he was my junior on a case, though I have no recollection of the case at all.'

Would he have been any good as a lawyer? 'Oh yes, I think so. When you listen to him, you want to agree with him.' I'd much rather agree with Tom Bingham, and vote for him, come to that.

Previous page

Previous page