FIDDLING WHILE FREEDOM FADES

Britain is doing little to save Hong Kong

from Chinese tyranny. Charles Moore reports

from a colony living in fear

LAST WEEK I visited the Sham Shui Po Vietnamese refugee 'closed centre' in Hong Kong. I interrupted Phong, a 42- year-old man, as he was painting a camp sign warning against fire risk. Why had he come to Hong Kong? I asked. In Vietnam, he said, he had been a potter, supplying designs that were then mass produced. There he had earned 7,000 Vietnamese dollars per month. A chicken cost 3,000 Vietnamese dollars, a letter abroad 4,000. Now he was earning about £60 per week for his job in the camp.

Phong was . fortunate because he reached Hong Kong at the end of May last year. On 16 June, the status of the Boat People changed: they ceased automatical- ly to be classified as refugees. Phong would probably now be dismis- sed as an 'economic mig- rant' and be threatened with repatriation if he arrived in Hong Kong today. (This, by the way, is the possible fate of his daughter. She was separated from her father's boat when he escaped, and reached Hong Kong a month la- ter, just after the rules had changed. She is now in one of the closed detention centres which journalists are not allowed to visit.) 'Anyway,' Phong went on, `I want to live in freedom, and do the work which gives me joy. Here I do live in freedom.' The refugee centre is surrounded by a high perimeter fence and barbed wire. Families of four sleep and keep all their belongings in boxes about eight foot by three stacked on top of one another inside metal han- gars. The chances of resettlement are remote. Yet I did not doubt that Phong was telling the truth. For him, this was freedom.

This is not an article about the fate of the Boat People. I only start with Phong's example to suggest that, even for the poorest and least wanted, freedom is the issue in Hong Kong.

There are others who can, literally, afford to think differently. Helmut Soh- men is a shipping magnate in Hong Kong and the son-in-law of Sir Y. K. Pao, perhaps the richest of the rich there. On 25 September he told the Guardian:

You must remember that while capitalism sometimes goes with democracy, you can have capitalism without democracy — as in Germany before the war. Communism is finished in China, and there is no alternative for them but to adopt capitalism. But the Communist Party is an essential 'force in holding the country together.

I heard a similar point of view from C. Y. Leung, a rich young man who works for Jones, Lang, Wootton. He is secretary- general of the consultative committee on the Basic Law — the law under which Hong Kong will be run after 1997. Mr Leung complained of the 'knee-jerk reac- tion' in Hong Kong to the events of Tiananmen Square. It was wrong to fright- en the Chinese, he said, and to demand too much. He favoured the new 'bicameral' plan for the government of Hong Kong. This resembles the South African system in that it is so constructed that the govern- ment must always win. It is the political structure that China favours.

As so often in recent years, it falls to Martin Lee QC, the most outspoken of the colony's politicians, to point out the perils. In a speech to the Legislative Council at the beginning of this month he said:

. . . the freedom of thought and expression

plays a vital role in our successful economy.

But if we were to be deprived of our free- dom of expression like our compatriots in mainland China, we would soon learn to res- train our thoughts so as to keep them out of trouble. And we would soon begin to think like slaves, and learn to take orders from Party cadres and only do what we are told to do. Now, if we cannot think free- ly, our society cannot

Already, too many in Hong Kong are learning to restrain their thoughts. At the end of May, about a million people joined Martin Lee in a protest on the streets. A couple of weeks ago, only 500 did so. It is not a coincidence that Hong Kong's econo- mic growth rate is dropping and enterpris- ing middle classes are applying for pass- ports in free countries that want their skills.

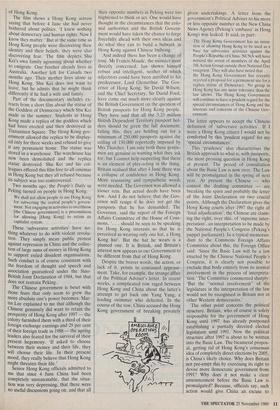

The day after visiting the refugee camp I sat in a tiny studio in Kowloon with Shu Kei, a young film-maker. We watched a rough cut of Sunless Days, his forthcoming documentary for television about how the massacres in Peking affected the attitudes

of Hong Kong. The film shows a Hong Kong actress saying that before 4 June she had never bothered about politics. 'I knew nothing about democracy and human rights. Now I know they matter.' But at the same time as Hong Kong people were discovering their identity and their beliefs, they were also discovering fear. The film depicts Shu Kei's own family agonising about whether to emigrate. One brother already lives in Australia. Another left for Canada two months ago. Their mother lives alone in Hong Kong. Shu Kei does not want to leave, but he admits that he might think differently if he had a wife and family.

Part of the documentary includes ex- tracts from a short film about the statue of the Goddess of Democracy which Shu Kei made in the summer. Students in Hong Kong made a replica of the goddess which had been erected and then destroyed in Tiananmen Square. The Hong Kong gov- ernment allowed the replica to be display- ed only for three weeks and refused to give it any permanent home. The statue was stored in a warehouse. The warehouse has now been demolished and the replica statue destroyed. Shu Kei andhis col- leagues offered this film free to all cinemas in Hong Kong but they all refused because its subject was too controversial.

Two months ago, the People's Daily in

Peking turned on people in Hong Kong: We shall not allow people to use Hong Kong for subverting the central people's govern- ment. Not engaging in activities to overthrow [the Chinese government] is a precondition for allowing [Hong Kong] to retain its capitalist system.

These `subversive activities' have no- thing whatever to do with violent revolu- tion. They simply mean public protest against repression in China and the collec- tion of large sums of money in Hong Kong to support exiled dissident organisations. Such conduct is of course consistent with the freedom of thought and speech and association guaranteed under the Sino- British Joint Declaration of 1984, but that does not restrain Peking.

The Chinese government is beset with those fears that only seem to grow the more absolute one's power becomes. Mar- tin Lee explained to me that although the Chinese genuinely did want to retain the prosperity of Hong Kong after 1997 — the colony furnished them with a third of their foreign exchange earnings and 29 per cent of their foreign trade in 1988 — the ageing leaders also feared for the survival of their present hegemony. 'If asked to choose between their money and their life, they will choose their life. In their present mood, they really believe that Hong Kong might threaten their life.' Senior Hong Kong officials admitted to me that since 4 June China had been completely unreasonable, that the situa- tion was very depressing, that there were no useful discussions going on, and that all their opposite numbers in Peking were too frightened to think or act. One would have thought in the circumstances that the colo- nial authorities and the British Govern- ment would have taken the chance to forge forcefully ahead with their own ideas and do what they can to build a bulwark in Hong Kong against Chinese bullying.

And indeed there has been a change of tone. Mr Francis Maude, the minister most directly concerned, has shown himself robust and intelligent, neither of which adjectives could have been ascribed to his predecessor, Lord Glenarthur. The Gov- ernor of Hong Kong, Sir David Wilson, and the Chief Secretary, Sir David Ford, have come out much more clearly against the British Government on the question of British passports for Hong Kong people. They have said that all the 3.25 million British Dependent Territory passport hol- ders should be given the full document; failing this, they are holding out for a minimum of 250,000 passports against the ceiling of 150,000 reportedly imposed by Mrs Thatcher. I am sure both these gentle- men are genuine in wanting what they ask for, but I cannot help suspecting that there is an element of play-acting in the thing. Britain realised that after 4 June there was a collapse of confidence in Hong Kong. More reassuring and sympathetic words were needed. The Governor was allowed a looser rein. But actual deeds have been few. And I do not believe that the Gov- ernor will resign if he does not get the passports that he has demanded. The Governor, said the report of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the House of Com- mons, . . should be seen to be speaking for Hong Kong interests so that he is perceived as wearing only one hat, a Hong Kong hat'. But the hat he wears is a plumed one. It is British, and Britain's interest now appears to our Government to be different from that of Hong Kong.

Despite the braver words, the action, or lack of it, points to continued appease- ment. Take, for example, the strange affair of the Political Adviser's letter. In recent weeks, a complicated row raged between Hong Kong and China about the latter's attempt to get back one Yang Yang, a leading swimmer who defected. In the course of the row, China accused the Hong Kong government of breaking privately given undertakings. A letter from the government's Political Adviser to his more or less opposite number in the New China News Agency (Peking's `embassy' in Hong Kong) was leaked. It said, in part:

The Hong Kong Government has no inten- tion of allowing Hong Kong to be used as a base for subversive activities against the People's Republic of China. NCNA will have noticed the arrest of members of the April 5th Action Group outside their National Day reception. They will also have noted that . . . the Hong Kong Government has recently rejected a proposal for a permanent site for a replica statue of Democracy. No group in Hong Kong has any more tolerance than the law allows. The Hong Kong Government will continue to have a prudent regard for the special circumstances of Hong Kong and the interests and concerns of the Chinese Gov- ernment.

The letter appears to accept the Chinese definition of 'subversive activities'. If I were a Hong Kong citizen I would not be comforted by this 'prudent regard' for my `special circumstances'.

This `prudence' also characterises the British approach to what is, with passports, the most pressing question in Hong Kong at present. The period of consultation about the Basic Law is now over. The Law will be promulgated in the spring of next year. At present the Chinese — who control the drafting committee — are breaking the spirit and probably the letter of the Joint Declaration on two crucial points. Although the Declaration gives the Hong Kong courts after 1997 the right of `final adjudication', the Chinese are claim- ing the right, over this, of 'supreme inter- pretation', an interpretation to be made by the National People's Congress (Peking's puppet parliament). In a typical memoran- dum to the Commons Foreign Affairs Committee about this, the Foreign Office said: 'Since the Basic Law will be a law enacted by the Chinese National People's Congress, it is clearly not possible to exclude that body entirely from its normal involvement in the process of interpreta- tion.' The Committee commented sharply: `But the "normal involvement" of the legislature in the interpretation of the law would not be recognised in Britain nor in other Western democracies.'

The other point concerns the political. structure. Britain, who of course is solely responsible for the government of Hong Kong until 1997, has already postponed establishing a partially directed elected legislature until 1991. Now the political structure after 1997 is about to be written into the Basic Law. The bicameral propos- al, getting rid of Hong Kong's consensus idea of completely direct elections by 2005, is China's likely choice. Why does Britain not pre-empt this by exercising its right to devise more democratic government from 1991? Why does it not make a clear announcement before the Basic Law is promulgated? Because, officials say, such action would give China an excuse to complain of provocation. The fact is that any British independence is provoking to China: Peking's very unreasonableness is taken by Britain as an additional reason for doing nothing instead of the most pressing reason for doing the opposite.

Delay itself strengthens China's hand. A twentieth of Hong Kong's remaining period of colonial rule has gone since 4 June. In that period, Britain has changed its tone, but it has given the people of Hong Kong nothing new, except two fresh foreign secretaries. It refuses to stand behind its own Declaration by giving them British passports and the resulting confi- dence that would persuade them to stay. They become more and more powerless to affect their fate.

And that, one is forced to conclude, is what Britain wants. One should never forget that the Joint beciaration is an agreement between Britain and China: Hong Kong has no standing in the matter. No referendum, no democracy, no self- determination. The end of Hong Kong shows the worst side of imperial rule. It reveals the ultimate powerlessness of the ruled. In a strange way, Peking and Lon- don are at one, and Hong Kong is set at nought. Peking likes what it sees of British colonial rule. It wants to grab that stability and prosperity, not seeing that those things also depend upon freedom. Britain wants no diminution of her colonial authority before 1997. It is much easier, much neater, much more congenial to the di- plomatic mind, to be able to deal from government to government, and forget about the actual people. It is said that I. M. Pei's vast new Bank of China building is bad feng shui (the lore of the positioning of objects) because its angle cuts like a knife through Government House. Sir David Wilson has planted a tree in the garden, at the request of his Chinese staff, to counter- act that threat. But China and Britain do not threaten one another. Together they point a knife at the heart of Hong Kong.

All the time I was in Hong Kong the comparisons with Eastern Europe rang in my ears. In Europe it really does seem that a 40-year policy of defiance and contain- ment is working, that the insistence on freedom is paying off, because freedom is what people want. In that respect, people in Hong Kong are no different from people in the West. Their misfortune is that, for all its protestations, Britain does not want freedom in Hong Kong. It wants out.

About 20 years ago, Douglas Hurd, now our Foreign Secretary, wrote, with Andrew Osmond, a thriller called The Smile on the Face of the Tiger. It concerned a Chinese threat to invade Hong Kong. In one scene, the Foreign Secretary, Ryder Bennett, is out shooting near Chequers, with the crisis on his mind. He comforts himself as follows: "What did it matter, after all? Even without Hong Kong there would still be pheasants in the woods and a Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs." '

Previous page

Previous page