ARTS

Theatre

Curtains for Hamlet

Christopher Edwards

Hamlet (Old Vic) The Beaux' Stratagem (Lyttelton) Salome (Olivier)

Here is a chance to witness an encoun- ter between Yuri Lyubimov, the exiled Russian director, and Shakespeare's Ham- let. It is a chance, too, to experience the thousand natural shocks that director's theatre is heir to. No text, I suppose, is sacred, not even that of the most famous play in the world. The fact that Lyubimov speaks no English makes Shakespeare's poetry less precious to his ear. In fact there is little evidence in this production that he is at all impressed by the dramatic adequa- cy of the verse. He was looking for 'a key to unlock the play'. He wanted to make the play work 'dynamically'. His own stated preference is for 'metaphors and images'. This is the language of the aesthetic sleuth. The play is a poser. It demands an aesthe- tic solution. Cuts and interpolations abound. 'To be or not to be' is split up between Claudius, Polonius and Hamlet. There is no sign of Fortinbras. Hardly any of the cast can cope with the blank verse. The action is jagged and gestures are given cartoon exaggeration.

Lyubimov's 'key' is a curtain that takes on a life of its own. It is the play's central prop, image, metaphor and dynamic. When it looms threateningly over the actors it is an effective tool of intimidation. To effect exits it is often lifted by the gravediggers wielding their shovels (the grave beckons at every turn). Most notably it suggests the furtive, spying, unprivate world that Denmark has become under Claudius. There is always somebody be- hind the arras. Hamlet's thrust, which kills Polonius, is an act of despairing defiance against this choking atmosphere. There are other neat metaphorical touches. Claudius's throne is not visible. All we see are spearheads forced through the curtain to form arm-rests.

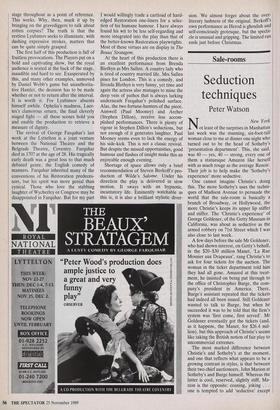

The curtain works nicely enough, even if at times you feel the actors run out of different ways of grabbing it, cloaking Daniel Webb as Hamlet and Anne White as Gertrude, at the Old Vic themselves in it, punching it and raising it. Aesthetically, it dominates the action. No one can get away from it. But it unlocks very little. More potent by far is Lyubi- mov's focusing on the grave. The play starts with the gravediggers burying a skull. The open pit is there at the front of the stage throughout as a point of reference. This works. Why, then, muck it up by bringing on the gravediggers to talk about rotten corpses? The truth is that the restless Lyubimov seeks to illuminate, with dashing expressive strokes, matters that can be quite simply grasped.

The first half of this production is full of fruitless provocations. The Players put on a bold and captivating show, but the royal audience is seated at the back of the stage, inaudible and hard to see. Exasperated by this, and many other examples, unmoved by Daniel Webb's game but unauthorita- tive Hamlet, the decision has to be made whether or not to return after the interval. It is worth it. For Lyubimov absents himself awhile. Ophelia's madness, Laer- tes's clamorous return, the final cleverly staged fight — all these scenes hold you and enable the production to retrieve a measure of dignity.

The revival of George Farquhar's last work at the Lyttelton is a joint venture between the National Theatre and the Belgrade Theatre, Coventry. Farquhar died in 1707 at the age of 28. His tragically early death was a great loss to that much debated genre, the English comedy of manners. Farquhar inherited many of the conventions of his Restoration predeces- sors, but his spirit was more genial than cynical. Those who love the stabbing laughter of Wycherley or Congreve may be disappointed in Farquhar. But for my part I would willingly trade a cartload of hard- edged Restoration one-liners for a selec- tion of his humane humour. I have always found his wit to be less self-regarding and more integrated into the play than that of the better-known Restoration playwrights. Most of these virtues are on display in The Beaux' Stratagem.

At the heart of this production there is an excellent performance from Brenda Blethyn as Mrs Sullen. A country lady who is tired of country married life, Mrs Sullen pines for London. This is a comedy, and Brenda Blethyn is very funny, yet time and again the actress also manages to mine the deep vein of pathos that is always lurking underneath Farquhar's polished surface. Alas, the two fortune-hunters of the piece, Aimwell (Paul Mooney) and Archer (Stephen Dillon), receive less accom- plished performances. There is plenty of vigour in Stephen Dillon's seductions, but not enough of it generates laughter. Paul Mooney seems even to lack the energy of his side-kick. This is not a classic revival. But despite the missed opportunities, good humour and flashes of insight make this an enjoyable enough evening.

Shortage of space allows only a brief recommendation of Steven Berkoffs' pro- duction of Wilde's Salome. Under his direction the play is delivered in slow motion. It sways with an hypnotic, incantatory life. Eminently watchable as this is, it is also a brilliant stylistic diver- sion. We almost forget about the over- literary lushness of the original. Berkoff's own performance as Herod is ghoulish and self-consciously grotesque, but the specta- cle is unusual and gripping. The limited run ends just before Christmas.

Previous page

Previous page