ARTS

Exhibitions

David Hockney (Royal Academy, till 28 January 1996)

Hockney's restless quest

David Ekserdjian Brandishing a postcard of a saucy Frag- onard, David Hockney was making front- page news a week or so ago. The choice was the very opposite of arbitrary, since the exhibition of his drawings now at the Royal Academy underlines the extent to which he has an affinity with the art of 18th-century France. The headline-making argument was about pornography and paedophilia, but Hockney's pert-buttocked young men are pure dix-huitieme, and about as danger- ous as Boucher's Miss O'Murphy, lying cheeks upward on a sofa. Indeed, in an age like our own, which finds it well nigh impossible to take comedy as seriously as tragedy, Hockney's eternal problem is that he is such a pleaser. Even faceless California street-corners are endowed with elegant sun-kissed charm, while Celia Birtwell — his favourite muse — is as fluffily pastel-hued as any ancien regime beauty. Their close friendship yields a rich harvest here, including a female nude that represents a rare inversion of the ostensibly asexual academic life studies executed by heterosexual artists, and almost makes one wonder if Hockney is a closet straight. The iron only really enters the soul in the earliest and the latest drawings. The most extraordinary thing about the series of works produced at the Royal College and just afterwards is that Hockney seems to have found his own spare, distinctive voice as soon as he arrived in the big city from Bradford. R.B. Kitaj recognised his gifts at once, and bought the drawing of a skeleton Hockney spent his first week at the college producing (It was the most beautiful draw- ing I had ever seen in an art school'), but Hockney was not a masterly technician in his twenties. It was a number of years later that he reapplied himself to his craft, and also began to do portraits, and the gulf between the work of the mid and late Six- ties is a vast one. Real mimetic virtuosity only comes with the Auden drawing and others like it, where the absence of colour is arguably an advantage. At this time, inanimate objects are scrutinised with the same affectionate precision as people, regardless of whether they are vegetables or views.

Having achieved a manner which com- bined discipline with grace, a lesser artist than Hockney might have been content to turn it into a formula, but instead there has ensued a restless quest for new answers to old questions, not all equally successful. I suspect I am not alone in finding the exper- iments with perspective a bit of a bore, and the Picasso-inspired facial regroupings dis- tinctly laboured, but much may be forgiven someone who has been so utterly deter- mined not to rest on his laurels. The simple sepia drawing of his mother on the day of his father's funeral in 1978 shows him at his most unadorned, but also exposes the futil- ity of some of the circus acts and conjuring tricks.

The inner circle of his friends and family has long been Hockney's favoured raw material, • and the transformation of the cuddly pink mum of the Seventies into the more starkly observed old lady of today reflects both the natural process of ageing in the sitter and a change in the artist. These recent studies of her asleep are among the most moving things her son has ever created.

Not all great artists have drawn — Titian did so rarely, Caravaggio and Velazquez almost never — and not all great draughts- men have been great painters. Hockney belongs to that august body of artists who have felt obliged to use drawings to make paintings, but have also regarded drawing as an end in itself. Most modern art feels the need to be gigantic, whereas almost all of these offerings are of a scale to fit on anybody's walls. Chance would be a fine thing, but, in the absence of a windfall on the Lottery, there are worse consolations than wandering among this beautifully hung and superlatively selected anthology. I would defy all but the most curmudgeonly of visitors to the peerless Sackler Galleries, which always seem to bring one that much nearer heaven, not to feel an added spring in the step on the way round.

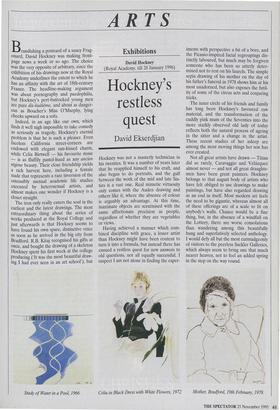

Study of Water in a Pool, 1966 Celia in Black Dress with White Flowers, 1972 Mother, Bradford, 19th February, 1978

Previous page

Previous page