CHESS

Grand prix

Raymond Keene

THE SUPPORT OFFERED by Intel to international chess has come in two forms, funding of the world championship and the foundation of a speed chess grand prix. The world championship has been well documented in The Spectator, and this week I turn my attention to the parallel competition, in progress for almost a year, which reached its climax in Paris in the sec- ond week of November. The grand prix consisted of four legs, held in Moscow, New York, London and Paris. Play was at accelerated time rates — knock-out games with just 25 minutes per player per game. In the result of a tie, time limits became even more alarmingly brief, with sudden- death battles, where the entire game had to be finished in just nine minutes.

The balance of every tournament was based on the formula: established world stars, plus qualifiers, rounded off by invi- tees from among the best players of the host country. The disadvantage of speed chess is that the quality of play often suf- fers, but there can be no doubt that with the knockout format and restricted time limits, the games can be nail-bitingly excit- ing. Indeed, agonisingly so, especially when grandmasters continually overlook obvious checkmates during time pressure, as hap- pened in one of the Ivanchuk–Anand encounters from London last year.

The grand prix is also popular with the players, since it guarantees, them substan- tial prizes. Kasparov, for example, picked up $125,000 in prizes and bonuses over the four legs, while Ivanchuk pocketed $95,000 and Kramnik took home $70,000. The two British grandmasters, Michael Adams and Jon Speelman, the best British performers in the league, collected $35,000 and $30,000 respectively. Such sums are quite unusual as prizes for chess tournaments, with the greatest rewards in the past having congregated in matches and qualifying bouts for the world championship. This week's game was the final blitz shoot-out between Kasparov and Kramnik which decided first prize in Paris. The whole game was played in less than ten minutes.

Kramnik–Kasparov: Intel Grand Prix, Paris, November 1995; King's Indian.

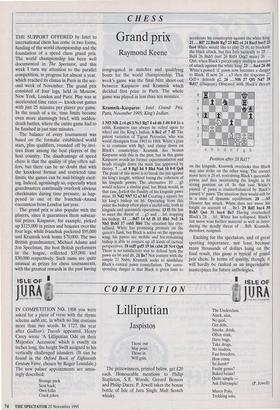

1 Nf3 Nf6 2 c4 g6 3 Nc3 Bg7 4 e4 d6 5 d4 0-0 In a crisis, Kasparov can always be relied upon to wheel out the King's Indian. 6 Be2 e5 7 d5 The patent variation of Tigran Petrosian, who was world champion from 1963 to 1969. White's plan is to continue with Bg5, and clamp down on Black's counterplay. Kramnik has beaten Kasparov with this in the past, but in this game Kasparov avoids his former experimentation and heads straight down the main line approved by theory. 7 a5 8 Bg5 h6 9 Bh4 Na6 10 0-0 Qe8 The point of this move is to break the pin against his king's knight, without losing the cohesion of his kingside pawns. The alternative 10 ... g5 would achieve a similar goal, but Black would, in that case, forfeit the fluidity of his kingside pawn mass. 11 Nd2 Nh7 12 a3 h5 Creating a square for his king's bishop on h6. Operating from this point the bishop often plays a useful role, both in kingside and queenside operations. 13 f3 He has to meet the threat of ... g5 and ... h4, trapping his bishop. 13 ... Bd7 14 b3 f5 15 Rbl Nc5 16 Nb5 BxbS 17 cxb5 Bh6 The situation has crys- tallised. White has promising pressure on the queen's flank, but Black is active on the opposite wing, his pawns are mobile and his remaining bishop is able to conjure up all kinds of tactical perspectives. 18 exf5 gxf5 19 b6 cxb6 20 Nc4 Qg6 There is no satisfactory way to defend both the pawn on b6 and d6. 21 Bel Not content with the simple 21 Nxb6, Kramnik seeks to annihilate Black's central pawn constellation. The corre- sponding danger is that Black is given time to accelerate his counterplay against the white king. 21 ...MI 22 Bxd6 Rg7 23 Rf2 e4 24 BxcS bxc5 25 fxe4 White would like to play 25 f4, to blockade the black attack, but this fails tactically to 25 .. • Bxf4 26 Bxh5 (not 26 Rxf4 Qxg2 mate) 26 ... Qh6, when Black's pieces enjoy multiple avenues of attack against the white king. 25 ... fxe4 26 d6 White's passed 'd' pawn now becomes a danger to Black. If now 26 ... e3 then the response 27 Qd5+ defends g2. 26 ... Nf6 27 Qfl Nd7 28 Rdl? (Diagram) Obsessed with Black's threats on the kingside, Kramnik overlooks that Black may also strike on the other wing. The correct move here is 28 a4, restraining Black's queenside pawns and thus maintaining the knight in its strong position on c4. In that case White's passed 'd' pawn is counterbalanced by Black's passed 'e' pawn. The situation then would still be in a state of dynamic equilibrium. 28 ...b5 Disaster has struck. White dare not move his knight on account of ...Be3, 29 Rd5 bxc4 30 Bxh5 Qe6 31 bxc4 Be3 Having overlooked

Black's 28 b5, White has collapsed. Black's last move wins further material as well as intro- ducing the deadly threat of Rf8. Kramnik, therefore, resigned.

Exciting for the spectators, and of great sporting importance, not least because many thousands of dollars hung on the final result, this game is typical of grand prix chess. In terms of quality, though, it will hardly be ranked as an imperishable masterpiece for future anthologies.

Previous page

Previous page