NUCLEAR POWER: THE FIFTH HORSEMAN?

Since Chernobyl, fear of nuclear power has grown. But how real are the dangers? And can Britain afford

THE week after Chernobyl, I went to the tiny, overcrowded, poor and friendly offices of Friends of the Earth to talk about nuclear power. The telephone was ringing day and night with terrified people be- seeching advice. One mother was weeping that she had let her children go out in the rain and she felt so guilty she was going to kill herself. Should I close all the windows? Should I burn clothes with mud on them? Should I boil all the water? What about the bath water? Is there anywhere, just one place in this cursed earth that is safe? New Zea- land perhaps? The staff at Friends of the Earth, Passionately opposed to nuclear power, told their callers not to panic.

And consider this fact. A piece .of Plutonium the size of an orange contains enough of the stuff to kill everyone on earth. The corollary that it would be quite impossible to distribute this orange for it to have any such effect does not seem reas- suring.

Another reason for fear is the problem of disposing of the waste. Dumping perish- able canisters in the sea is clearly indefensi- ble. Joan Ruddock made a powerful point at the Labour Party Conference when she said that we do not inherit the earth, we have it on loan for our children. In that context it is hard to justify the expansion of an industry whose by-products are deadly poisonous and will remain so for centuries. Finally, of course, there is the terror of a catastrophe like Chernobyl. It could easily have been infinitely worse, and the Fifth Horseman's loathsome rays could have swept even vaster areas than they did, condemning millions of children to death in years and years to come.

Just before Chernobyl the Economist carried a cover exquisitely entitled 'The charm of nuclear power'. After the event, it was more fashionable to declare that it had been inevitable all along. 'Bound to happen', announced the Observer with some pomp. The only worthwhile ques- tions were when and where'.

But if it was 'bound to happen' once, it is presumably bound to happen again, de- spite all the extra precautions which (one assumes) even the Russians will now take. Windscale, Three Mile Island, Chernobyl — each involved human errors and each was more dangerous than the one before. It is hardly surprising that nuclear power, like nuclear defence, is now an election issue.

It is not so in France. Since 1973 nuclear power has become perhaps the most im- portant part of France's economic strategy for the 21st century. It already provides over 60 per cent of France's electricity. In England and Wales the figure is about 19 per cent. In Scotland it is 50 per cent.

Similarly, Alastair Goodlad, the present L under secretary of state for energy, recently vi- sited a vast new nuclear power station and repro- cessing plant in Brit- tany. He asked the pre- fet how it had all been constructed so fast.

'How long did that take?' asked Goodlad.

'Deux mois.'

'And what did you do with the written depositions?'

'Dans la mer.'

Not quite the same as our own dear inquiry as to whether a new pressurised water reactor should be built at Sizewell.

This has been an extraordinary event. A single inspector, Sir Frank Layfield, has spent two very serious years scrupulously taking evidence from hundreds of people and groups. Poor Sir Frank suffered a heart attack in the course of it all. His vast report was delayed and delayed but is now about to be delivered to Peter Walker, the energy secretary.

Walker is a zealot for nuclear energy. In a speech after Chernobyl he declared that to abandon it would be to 'leave our children and grandchildren a world in deep and probably irreversible decline'. His speech was denounced by Friends of the Earth as 'inaccurate, dishonest and hyster- ical'.

These are the sort of terms in which the nuclear debate is conducted. They do not make it easier to find out what is really needed. I must confess at this point that this article offers no absolute truth of which I have become certain.

Nuclear power in its present form is seen by its proponents as at least a stopgap until the time when fossil fuels run out — some time next century — and alternative sources of energy become viable. The long term probably lies with nuclear fusion, which is much safer than present fission; but it is probably 50 years away.

But would there actually be an 'energy gap' without nuclear power? And if so, would the consequences of that gap be worse (in different ways) than the risk of keeping the horseman with us? In part it all depends on the assumptions on which economic forecasts are based. How fast will the world economy grow? What will be the demand for electricity in 40 years time? When will oil really run out? No one can know.

But one thing is obvious. Politically, the industry has gone critical. The Liberals are against it. The Labour Party narrowly defeated a demand by Arthur Scargill (who has his own very obvious special agenda) to scrap it at once, but Labour is now committed to phasing it out 'over decades' and will stop Sizewell B. The SDP wants a pause, so only the Tories are all in favour of its retention and expansion. Alastair Goodlad is about to gird up the party workers. He reckons the 'Chernobyl effect' is already fading. I doubt it. And I hope not. But if no new station is built at Sizewell, everyone seems to agree it will be the virtual end of the nuclear power in Britain. The scientists will go elsewhere.

For a glimpse of the official British case, I went first to see Lord Marshall, the chairman of the CEGB, a grand old warrior in the cause of nuclear power. In some ways, Walter Marshall is a tragic figure. He is one of those who believed passionately at the start of the British civil nuclear programme, over 30 years ago, that postwar Britain desperately needed the new cheap energy which nuclear power seemed to offer. At that time it seemed as if the demand for electricity for the steel, chemical, aluminium and other industries would be infinite. Fossil fuels should still be used, but they might either run out or become prohibitively expensive. Nuclear energy seemed clean and safe. It was the future.

But it has not worked. Or at least not as well as its prophets hoped. Nowhere in the world has nuclear power provided the very cheap, very safe power promised in the 1950s. The nuclear industry now seems to many people centralised, secretive, dishon- est and a failure, as well as dangerous. British policy has been a mess. The first generation of stations were the Magnox stations; eight were built between 1962 and 1971. They proved relatively safe, but they did not make electricity dramatically cheaper.

Then we started building advanced gas- cooled reactor stations, or AGRs, between 1976 and 1985. Each was different from the other, so each was really only a prototype. The cost over-runs were fantastic. The first two had to be closed down just one hour after they were started up because of design defects; it took a year to correct their faults. So the CEGB decided next time to go for pressurised water reactors, which had been developed and built in the United States and in France and which seemed to offer cheaper electricity than either Magnox or the AGRs. There are now plans for four, the first to be Sizewell B. Then came the accident in the PWR at Three Mile Island, and subsequently the Government tapped the long-suffering Sir Frank Layfield on the shoulder.

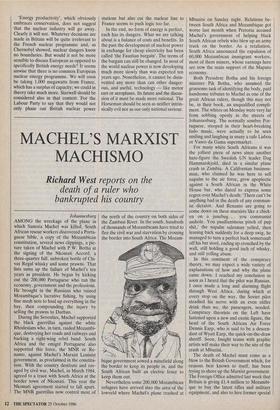

In his office in the shadow of St Paul's, Lord Marshall, a large and avuncular man, who devised much of the strategy which defeated Arthur Scargill, leant back in his chair and said, 'Look ahead to the year 2020, a short time in the energy business. The only large oil fields we know will still be operating are in Saudi Arabia. The North Sea will be finished. Alaska will be finished. Iran will be finished. So we can assume that oil will be much higher priced. We will still be using gas, but most people come to the conclusion that there must be a massive use of coal:, 'Now,' he said, 'I will make an extremely generous assumption — that coal produc- tion around the world is five whole times as Nuclear reactors worldwide Existing Reactors Under Construction"

Percentage of electricity generated by end 1985 USA 93 26 15.5 France 43 19 64.8 USSR 51 34 10.3 Japan 33 11 22.7 West Germany 19 6 31.2 UK 38 4 19.3 Belgium

0 59.8 Taiwan 6

53.1 Spain 8 2 24.0 Switzerland 5 0 39.8 South Korea 4 5 22.1 East Germany 5 6 12.0 Hungary 3 2 23.6 Argentina 2

11.3 Mexico

2 00.0 'Including reactors which may never be commissioned Source: Atomic Energy Authority

much as it is today. I think that's over- generous,' he said. I thought so too.

'Now, assume that we have all that coal, that oil is past its peak, and that we have no nuclear power. If you share the available energy equally around the world, you'll find that every Englishman and every American has to have less energy than the Mexican peasant has now.' He went on to say that if we abandon nuclear power we will be competing fiercely with the Third World for increasingly scarce fossil fuels. This would be unfair on the Third World. 'Ethics is on our side.'

Let's look at the figures more minutely. The core of the CEGB's case goes like this. The CEGB's current total capacity is 56,000 megawatts — 52,000 in operating and 4,000 in reserve plant. The peak demand, at 4-5 p.m. on winter weekdays, is about 46,000 megawatts. In the early 1990s, the CEGB claims that that demand will have risen to 50,000 megawatts. They also reckon having to plan for a surplus of about 28 per cent — in case of breakdown, routine maintenance and so on.

Our eight Magnox and four AGR reac- tors now produce about 6,000 megawatts. A fifth AGR is due to come on line next year at Heysham. The Magnoxes are due to be phased out from the 1990s.

The CEGB forecasts that demand for electricity will grow at 11/2 per cent per annum. John Baker, Lord Marshall's de- puty, says that if we abandon nuclear power, that means that by 2000 we will need 12 to 14 new coal-fired power stations — or another 10,000 megawatts of capac- ity. To be in operation by 2000, they would all have to be planned and approved by 1994.

The national grid can shift only a limited amount of power. So Baker says that some of them would have to be in the South. Plymouth and Marchwood near South- ampton are amongst the sites considered. New bunkerage and port facilities and a large increase in internal rail services would be needed. Planning consent for all of them would be bitterly contested.

We would need at least 100 million tons of coal in 2000 against the 75 million tons burned today. Will it be provided by Mr Scargill or will it be imported? Whatever, the price is going to go up, says the CEGB — perhaps by as much as 30 to 50 per cent. This figure is said by nuclear power's opponents to be a vast exaggeration, parti- cularly if the reactors were shut down only gradually. Still, some increase would be inevitable. That would have a major im- pact on many industries such as chemicals, paper, board, glass, steel. The CEGB reckons it would lead to a progressive disinvestment by those industries in the UK.

And that, of course, brings us back to the French connection. The French have actually built too many nuclear power stations. There are 43 finished and 19 under construction. They are now offering new industrial customers a guaranteed tariff to the end of the centurys reducing by at least one per cent in real terms a year.

The waste disposal problem is, for many people, the most acute. An industry whose wastes will be dangerous for hun- dreds or even thousands of years surely cannot be justified?

The CEGB has spent a lot of money trying to dispel such fears — like having a train crash into a container of spent fuel rods to show the container surviving intact. Lord Marshall describes.with relish all the natural radioactivity with which we are surrounded. But public attitudes have not changed.

It is not just Lord Marshall. An excellent Channel 4 series last summer showed that in fact only a tiny amount of the radioactiv- ity in the world comes from nuclear power. Indeed, 87 per cent of the radioactivity comes from the nature of the earth itself. Of the non-natural radioactivity 111/2 per cent is medical, lh per cent is from fallout from weapons testing, 1/2 per cent from such phenomena as air travel and luminous watches, just under 1/2 per cent from other industries, and one tenth of one per cent from the nuclear industry. Of course Sellafield's discharges into the sea do increase the amount of radioactivity in the water. But there are constant tests on critical groups of people exposed to radioactivity to see whether they are affected. Channel 4 reported that pluto- nium from Sellafield is absorbed by wink- les. So winkle-eaters in the north-west are monitored. Only negligible amounts of Plutonium have been found in the pooled urine of even the most dedicated winkle- eaters.

It is estimated that perhaps 30 or 40 people will die in the United Kingdom from cancer caused by nuclear power over the next 30 years. Maybe that is a lot, but at the same time between three and four million others will die of cancer from other causes — such as smoking. X-rays alone will cause 1,000 deaths in that period. X-ray machines could be made safer, but there is little public concern. Similarly, there is a one in 1,000 chance of being killed or injured in a car in this country, but that has not led to any demand for lower speed limits (which undoubtedly save lives). Then again, the chemical in- dustry is also very dangerous —28 people were killed at Flixborough in 1974. But chemical dangers do not sear the soul. Only nuclear energy does that. The coal-fired stations with which Arthur Scargill would have us replace nuclear power would inevitably cause more acid rain and contribute to the even more terrifying 'greenhouse effect' — the warm- ing of the atmosphere. According to Nasa, the greenhouse effect in the next 50 years will warm the earth twice as much as it did in the previous 130.

The opponents of nuclear power, led by groups such as Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth, argue, rightly, that the alterna- tives have not been adequately explored. First of all, there is conservation and increased efficiency. (David Howell called conservation 'the fifth fuel'.) The best coal-fired power station is now only 38 per cent efficient. Friends of the Earth claim that improvements could reduce UK de- mand by the equivalent of three Sizewell Bs by the year 2000.

Another alternative source of energy now being considered in the USA and here is wind power. Wind technology has really developed only since the oil crisis of 1973. There are problems. Windmills or turbines are large and ugly and sound like a helicopter. Our windiest areas tend to be hilltops near the coast: who is going to want to see the cliffs of Cornwall covered with vast roaring turbines up to 100 yards in diameter? Offshore turbines seem a better bet. In California, turbine machines appear to be proving reliable and to be producing electricity cheaper than nuclear or coal-powered stations. One expert, Pro- fessor Peter Musgrove of Reading Uni- versity, reckons that it would be possible in theory to generate 20 per cent of total UK electricity through wind power.

Wave power no longer seems as attrac- tive as it did, but tidal power is still exciting interest. Even the CEGB acknowledges that a barrage across the Severn .could produce up to five per cent of the UK's electricity needs and told the Sizewell enquiry that perhaps in the 21st century tidal power and wind power could produce five–ten per cent of energy needs. Friends of the Earth declare that all the renewable forms of energy — solar, waves, tides, wind, and the burning of wastes, biomass, etc — might provide 20 per cent of our energy needs in 2025. They argue that the Government, obsessed with nuclear pow- er, gives far too little money to research into the alternatives. This seems undeni- able. In 1984-5 the Department of Energy spent almost £200 million on nuclear re- search and £47.5 million on non-nuclear research and development, including only 'I forget. Are we tit or tat?' £14 million on alternative sources.

These are general objections to the development of nuclear power. There are also specific objections to the idea of a pressurised water reactor at Sizewell B.

The CEGB's 'risk assessment' of a serious nuclear accident at Sizewell B is less than one in a million years. But the Nuclear Regulatory Commission in the USA agrees there could be an accident like Three Mile Island every ten years.

Operator error was responsible for both Three Mile Island and Chernobyl. But when things go wrong in a PWR they do so much faster than in an advanced gas- cooled reactor. The PWR produces heat very, very fast, and that heat has to be taken away very very fast. At both Three Mile Island and Chernobyl, the water coolant was lost, and at Chernobyl the operators failed to prevent a disaster.

Although the designs are different, a similar accident could in theory happen in the British PWRs. The main advantage of the older gas-cooled reactors we have is that when there is an accident the oper- ators have much more time to discover the problem before the reactor goes out of control.

Perhaps the bottom line of the CEGB and the Government's argument for Sizewell is strategic. If we do without nuclear power not only will electricity become more expensive, but we will again be at the mercy of both Opec and Arthur Scargill. This was emphasised with great vigour by Lord Marshall to me.

But that strategy could be maintained by sticking with the AGR designs that we have and building more of those instead of the PWRs. The latest AGRs at Torness and Heysham II are being built to cost and time, and in 1985 the AGRs at Hinkley Point and Hunterstone were on line for 75 per cent of the time — a much better efficiency record than in the old days. They might cost even more than the proposed PWR programme, but they would prob- ably be safer. The Scottish Electricity Board argued strongly for this option at the Sizewell inquiry.

There is another way of looking at all of this, which has been proposed by the Institute for European Environmental Policy. Till now almost every country's energy policy has been to produce it as cheaply and safely as possible. Perhaps what is needed is a switch to producing and using it as efficiently as possible. Put another way, we should be more con- cerned about 'energy productivity'. The Institute proposes that utility companies should not strive just for cheap energy and the highest possible turnover. Instead of supplying energy, they should be asked to manage it, thus profiting from energy productivity rather than energy waste. At the moment the opposite happens. 'Energy productivity', which obviously embraces conservation, does not suggest that the nuclear industry will go away. Clearly it will not. Whatever decisions are made in Britain will be quite irrelevant to the French nuclear programme and, as Chernobyl showed, nuclear dangers know no boundaries. But would it not be more sensible to discuss European as opposed to specifically British energy needs? It seems unwise that there is no common European nuclear energy programme. We will soon be taking 1,000 megawatts from France, which has a surplus of capacity; we could in theory take much more. Sizewell should be considered also in that context. 'For the Labour Party to say that they would not only phase out British nuclear power stations but also cut the nuclear line to France seems to push logic too far.

In the end, no form of energy is perfect, each has its dangers. What we are talking about is a balance of costs and benefits. In the past the development of nuclear power in exchange for cheap electricity has been called 'the Faustian bargain'. The terms of the bargain can still be changed. In most of the world nuclear power is now developing much more slowly than was expected ten years ago. Nonetheless, it cannot be disin- vented any more than can other danger- ous, and useful, technology — like motor cars or aeroplanes. Its future and the discus- sion of it must be made more rational. The Horseman should be seen as neither intrin- sically evil nor as our only national saviour.

Previous page

Previous page