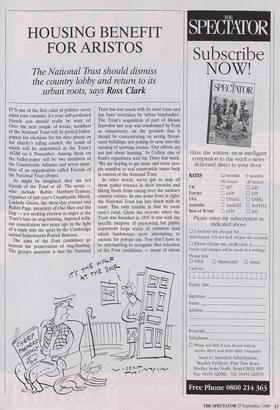

HOUSING BENEFIT FOR ARISTOS

The National Trust should dismiss the country lobby and return to its

urban roots, says Ross Clark

IT'S one of the first rules of politics: never mind your enemies, it's your self-professed friends you should really be wary of. Over the next couple of weeks, members of the National Trust will be posted ballot- papers for elections for the nine places on the charity's ruling council, the result of which will be announced at the Trust's AGM on 6 November. Among those on the ballot-paper will be two members of the Countryside Alliance and seven mem- bers of an organisation called Friends of the National Trust (Font).

As might be imagined, they are not friends of the Trust at all. The seven who include Robin Danbury-Tenison, organiser of last year's Countryside March, Lucinda Green, the three-day eventer and Robin Page, presenter of One Man and His Dog — are seeking election in anger at the Trust's ban on stag-hunting, imposed with- out consultation two years ago in the light of a study into the sport by the Cambridge animal behaviourist Patrick Bateson.

The aims of the Font candidates go beyond the preservation of stag-hunting. The group's assertion is that the National Trust has lost touch with its rural roots and has been overtaken by 'urban busybodies'. The Trust's acquisition of part of Mount Snowdon last year was condemned by Font as unnecessary, on the grounds that it should be concentrating on saving threat- ened buildings, not poking its nose into the running of sporting estates. 'Our efforts are not just about hunting,' Jo Collins, one of Font's organisers, told the Times last week. `We are hoping to get more and more peo- ple sensitive to real countryside issues back in control of the National Trust.'

In other words, we've got to stop all those pinko townies in their anoraks and hiking boots from taking over the nation's country estates. In one sense Font is right: the National Trust has lost touch with its roots. The only trouble is that its roots aren't rural. Quite the reverse: when the Trust was founded in 1895 it was with the specific purpose of preserving for public enjoyment large tracts of common land which landowners were attempting to enclose for private use. You don't have to be anti-hunting to recognise that selection of the Font candidates — many of whom have publicly opposed the 'right to roam' over open moorland on the grounds that mass access would damage shooting and other country sports — would amount to a reversal of, not a return to, the Trust's original aims.

Far from being the creation of country- folk, the Trust was the brainchild of a lawyer, Sir Robert Hunter, who would fit perfectly the countryside lobby's idea of an 'urban busybody'. Son of a ship-owner and native of Camberwell — then already a sub- urb of London — Hunter, like many Lon- doners, was . incensed by an attempt to enclose a large swathe of Hampstead Heath in 1865. The ancient right of locals to per- ambulate and ride about the Heath was to be ended — an erosion of freedom with which huntsmen, with their own pastime now under threat, might perhaps be able to empathise. The battle to save Hampstead Heath led to the creation of the Commons Preservation Society, under which guise Hunter helped to save from enclosure Wandsworth and Wimbledon Commons, Putney Heath and Epping Forest.

Hunter then teamed up with Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley, a Lake District cler- gyman, and Octavia Hill, another 'urban busybody' from Camberwell, whose work with the poor led her to the conclusion that a lack of open space contributed to the misery of life in the slums. In modern parlance, Hill would be described as a mil- itant rambler: she organised mass trespass- es in order to reclaim lost footpaths in Kent, much to the chagrin of local landowners.

In 1895 Hunter, Rawnsley and Hill founded the National Trust, and the acqui- sition of property began. Early purchases were in keeping with Hunter's ideal of maintaining open spaces for the masses: they included Tintagel in Cornwall, Bran- delhow in the Lake District and Wicken Fen in Cambridgeshire. Snowdon, had it been for sale, would no doubt have been on the original shopping list. Stately homes, though, had nothing to do with it. It wasn't until the 1930s that the Trust began its transformation into the role it fulfils today: a housing association for bankrupt aristocrats. In 1937, with the upper classes still reeling from the Great Depression, the National Trust launched its Country Houses Scheme, which allowed the owners of failing estates to gift their property to the Trust in lieu of tax to the government. Part of the deal was usually that the owner's family would be allowed to live on in part of the house, allowing them to continue their privileged lifestyle without having to worry about the cost. New roof, darling? Let the visitors pay for it. Electric light? Don't worry — nice man from the Trust is seeing to that. In a sen- tence, the Trust became part of the 'some- thing for nothing' society, a mechanism for insulating the upper classes from the reali- ties of capitalism.

It is thanks to the Country Houses Scheme, for example, that an idle coke- head like the late Marquess of Bristol was able to squander his fortune in the comfort of .the west wing of Ickworth House rather than in some squalid bedsit in Fulham, where perhaps he deserved to end up: Ick- worth was gifted in lieu of tax in 1956. While the Marquesses of Bristol of this world are undoubtedly interesting anthro- pological specimens, one does have to ask whether providing them with lodgings quite comes under the Trust's stated aims: 'the preservation, in perpetuity and for the benefit of the nation, of land and buildings of historic interest or natural beauty'.

You only have to open a National Trust handbook to realise the extent to which the organisation has become biased towards the preservation of the minutiae of 18th-centu- ry aristocratic life. Nine-tenths of properties are preposterous houses put up in a frantic game of one-upmanship by Regency and Georgian gentlemen who kept sticking on extra wings to impress each other in the same way that Essex men stick go-faster stripes on their cars today. They were hous- es which, by their very expense, doomed their creators from day one; the idea that one day Joe Public would happily pick up the tab for their decadent lifestyle would have left them reeling with that manic, 18th-century giggle adopted by Mozart in the film Amadeus.

There was a time, after the last war, when perhaps the acquisition of country houses by the National Trust was neces- sary in order to save them from decay and demolition. But it is no longer so: the resurgence of private wealth has ensured that there is a market for country houses once more. They should be left alone to the nouveaux riches, such as Ann Gloag, the entrepreneur who co-founded the bus company Stagecoach, and who has since bought the Clan Fraser's stately pile, Beaufort Castle. Those no longer suitable as single homes can be turned into hotels, or split down the middle and turned into several houses. Not only do developers these days observe high architectural stan- dards when it comes to altering buildings, they are also able to keep buildings alive, rather than let them become dusty muse- um pieces.

If the Trust needs something doing to it, it's certainly not having more countrymen appointed to its ruling council; that will just mean more country houses preserved in aspic, more distressed gentlefolk saved from the indignity of having to pack up their belongings and move out. Perhaps, instead, there should be a movement to return the Trust to its urban origins by buying up playing-fields threatened by municipal greed, meadows earmarked for out-of-town shopping centres, and some of the common lands currently closed off by barbed wire and out of bounds to the mod- ern-day Octavia Hills, whom the country lobby so despises.

Previous page

Previous page