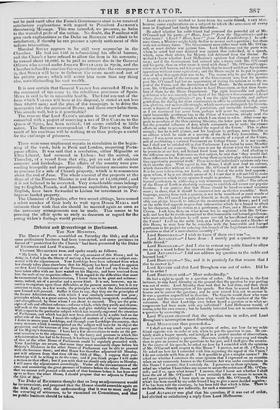

• 33cbatril an)i tame rbingt in Parliament. THE NEW MINISTRY.

The House of Peers assembled on Saturday the 18th; and after some preliminary business had been transacted, and some petitions in favour of "protection for the Church" had been presented by the Duke of RiCHMOND and Lord WienLow, Viscount MELBOURNE rose, and spoke nearly as follows.

"My Lords, I rise now to move the adj -urnment of this House; and in doing so, I shall take the liberty of making a few observations on a subject con- nected with the adjournment. Your Lordships hive been informed from what has already taken place elsewhere, that his Majesty has been pleased to appoint me first Lord Commissioner of the Treasury, and that I and my friends who have taken office with me have waited on his Majesty, and have received from him the seals of our respective offices. With regard to the difficulties that must he encountered by this Administration, I know them to be great and arduous : many, indeed, are of a peculiar and a severe kind. It is not, however, niy in- tention to expatiate upon these difficulties at the present moment ; but it is my intention to state, in a few words, the principles on which the Administration now formed will proceed. Suffice it then to say, that they are the principles of the former Administration, with which I was similarly connected last year ; principles which, to a great extent, have been admitted, recognized, confirmed, and strengthened, by those whom I am about to succeed. They are the prin- ciples of safe and efficient reforms—reforms which, while they purify Auld cleanse, will seek at the same time to strengthen awl give stability to our institutions. With respect to the particular subject which has recently engrossed the attention of Parliament, and which has just now been adverted to by a noble lord on the other side of the House, I mean the subject of matters of a religious character, I desire to assure your Lordships, and through yuur Lordships the country, that every measure which is contemplated on the subject will have for its object the promotion and the increase of true piety throughout the whole and every part of his Majesty's dominions, I have but a few observations to make on the pre- sent occasion as to the adjournment. In the hurry awl pressure in which this Administration has had to be formed, it hasbeen impossible that all the business of this or the other House of Parliament could be regularly proceeded with. Your Lordships are aware, that some time must necessarily elapse before his Majesty's Ministers in the other House of Parliament can be able to proceed with the business there; and that Reuse has therefore adjourned till Monday, and will adjourn from that time till the 12th of May. I suppose that your Lordehips will be willing to do the same, and if you think proper I will make a motiou to that effect ; but if you wish that we should only adjourn to Monday, I will move the adjournment accordingly. Under all the circumstances of the ease, arid considering the great pressure of business before the other House, and akar we cannot well proceed with much of that business before it has been sent up to us from the other House, I should propose that we adjourn to Tuesday the 12th of May." Ile Duke of RICHMOND thought that so long an adjournment would be inconvenient, and proposed that the House should assemble again on the euth April; with the understanding that it was to meet only for the swearing of witnesses, to be examined on Committees, and that no public business should be taken. Lord ALVANLEY wished to have from his noble friend, Lori Alel- bourne, some explanations on a subject to which the 'Memnon of every man in England had lately been directed— He asked whether his noble friend had procured the powerful aid of Mr. O'Connell and his party—(" Hear, hear ! " from the Opposition)—and on what terms ? (Loud " Hear, hear !" frema _Lord Londonderry.) In or-

nary times, a Minister might fairly decline to answer such a question ,• but these were not ordinary times. The Government must either treat with Mr. O'Con- nell, or must declare war against him. Lord Melbourne and the party with

evhom he acted had once declared war against that individual, in a speech, which, upon their advice, his Majesty had delivered from the throne. He wished t' know whether Lord Melbourne's opinions had changed since that rime; sod if the Government bad entered into a treaty with Mr. O'Connell and his party, then on what terms it stood with them? .Mr. O'Connell's oppo-

sition was well known, and it was not likely that he would withdraw his virulent

opposition 'without some equivalent ; and the House ought to be put in posers- S10151 of what that equivalent was to be. The reason why he put this question at so early a period of the existence of the Government was, that for months pest Mr. O'Connell had lost no opportunity of stating his opinion as to the re- peal of the Union, and the destruction of that House. In the autumn of het

year, Mr. O'Connell addressed a letter to Lord Dinicannon, at that time Secre-

tary of State for the Home Department. 'flee right honourable and gallant g,relernan who was recently at the head of his Majesty's Covernmeut—(Lool cheers front the Ovpositime)—" yes, I say the right honourable and gallant

gentleman, for during his short continuance in office he exhibited in that ardu- ous, glorious, and memorable struggle, which must ever distinguish his Govern-

ment, a degree of moral courage, of patriotism, and invincible fortitude, such as I mini convinced has never been, perhaps will never be, surpassed. That right honourable gentleman has, in the House of Commons, already read the

letter written by Mr. O'Connell to which I am about to refer. After some ap-

peals to members of the then existing Ministry, the letter goes on thus= I do feel the powerful iuduence of duty which commands nie to make the utmost

efforts in order to procure for Ireland the repeal of the Union."fhis is Ann enough ; but he is still plainer, and his language is, perhaps, more forcible In an address which he made at a meeting of the Anti-Tory Association. Ile says—' I was never Inure convinced of the necessity of a repeal of the ITnion, and of establishing a national Parliament on College Green. It is not vanity, but I shall not he satisfied till in that Parliament I am hailed by some Member as the father of v country. The time is not far distant when the Union will be prostrate at our feet, and Ireland freed from her chains.' And alluding to the difference among Reformers on that subject, he said that ' they would sink those differences for the present, and bring them again into play when a more fit-

ting opportunity presented itself.' Ilese were that individual's opinions only two short months ago. With regard to this House, I shall now read an extraet,

which shows that without its abolition Mr. O'Connell will not he contented.

It is for your Moen-Wien, my Lords, and for that of the noble lord oppositie ; upon whom, if he is not already aware of it, I trust that it will not fail to make

the impression which in my opinion it ought to produce. The honourahle and learned gentleman, in addresoug a very numerous meeting, said—' The reform of the House of Lords is absolutely necessary to establish arid secure our popular freedom. I am anxious that that House should be based on souud common

sense ; in short, that it should he converted into an elective assembly.' Stith language, coining from such a quarter, is not to be considered as mere words of couree. Mr. O'Connell has pledged himself, as deeply as any public man pos- sibly can pledge himself, to subvert the constitution of this House; and I call on the noble lord opposite to give that information which he is bound to afford

by his character, and his station as a gentleman, a Peer, and a Minister of the

Crown. I ask him, then, on what terms hae be negotiated with Mr. O'C..no- ne11; awl how far he stands committed to that honourable and learned geutleman, who most solemnly declares he will never rest till he has effected the repeat of the Union? I call on the noble lord, as a Veer of the realm and a Member of this House, to state how far he coincides with the honourable and learned gentleman in his project for reducing this branch of the Legislature to so humble a position as that of a mere elective assembly? " Lord BROUGHAM—" I wish to know if there ever was "— Lord ALVANLEY—" I have done : I merely put a question to my noble friend." Lord Bnouenem—" And I rise to entreat my noble friend to allow me to say a word before he answers that question." Lord ALVANLEY—" I did not address my question to the noble and learned lord."

Lord Baouerrear—" No; and it is precisely for that reason that I rise to answer it."

Lord KENYON said that Lord Brougham was out of order. Did he rise to order ?

Lord BROUGHAM said—" Most undoubtedly."

He had a right to speak to a question of order. He had risen, in the f ret instance, to stop Lord Alvanley on the ground that the question he was putting

was out of order. Lord Alvaiiley then said that he had done, and then there was no longer any interruption of his speech. But then he craved Lord Mel- bourne not to answer the question; and he now craved him not to answer it. It was a question unparalleled in disorder. The Gazette would show who were

in place, and the measures would show what would be the conduct of the Go- vernment. Had their LordAips ever before heard a question as to what ar-

rangements had been made with any individual? Lord Melbourne would, of course, take his on-n course; but he humbly intreated him not to sanction such a question by answering it.

Lord Wreeeow observed that the question was in order, and Lord Brougham's interruption most disorderly.

Lord MELBOURNE then proceeded— "I shall not say much upon the question of order, nor how far my noble friend opposite was in order or not, when he put the question to me. He cer- tainly made a longer speech, and indulged in a greater number of observations, than is usual in putting a question. However, nothiag is more easy and simple than to give an answer to the questions he has put, and I shall give the answer. In the coarse of his speech, he asked me bow far I coincided with the opinions of Mr. O'Cornell with respect to this House? I answer, not at all. ( Mere.) He asked me how far I coincided with him regarding the repeal of the Union ? I do not coincide with him at all. h it possible to give a simpler answer? He asked me whether I entertain the same opinion that I expressed on an occasion when an act commonly known as the Coercion Act was under consideration in this House? I answer, that I certainly do. I persevere in those opinions. He asked me whether I have taken any means to secure the assistance Or Mr. O'Con- nell; and if so, upon what terms? I answer, that I know not whether I shall have the aid of Mr. O'Connell : I have certainly taken no means to secure it, and most particularly I have made no terms with Mr. O'Connell. To that which has been stated by my noble friend I beg to give a most decided negative : if he ha e been told the contrary, he has been told that which is false. There is no foundation, directly nor indirectly, for such a statement."

Lord ALVANLEY was glad that his question, if it was out of order, bad elicited so satisfactory a reply from Lord Melbourne.' The Duke a BUCKINGHADI hoped the country would profit by Lord 3delbourne's satisfactory reply—

Rumours, however, had got about that great pains had been taken to conci- liate Mr. O'Connell. It was now found that that was not so. Lord Melbourne lad stated that the measures of his Government would have the same principles for their foundation as the measures of the Governraent of which he had before Sormed a part, and that all his measures would be directed to increase the usefulness

• f—[The Duke of Buckingham was here corrected by Peers on both sides of the House.] On what principle had the late Government resigned their situations? It was on this principle, that being beaten on a question in the other House of Parliament by that House adopting a resolution that no measure relating to the Church of Ireland would be satisfactory unless a clause was introduced for ap- propriating the surplus funds of that Church, if there were any surplus funds of the Church, to other purposes than those of the Protestant faith, they resigned rather than carry that resolution into effect. Now he might be permitted to ask Lord Melbourne emphatically and distinctly, whether he was prepared, acting as he said in the interests of true religion, to bring forward a measure for the regulation of the tithes of Ireland on the principle that the surplus, if any, should be applied to other than religious purposes?

Lord MELBOURNE said, with marked emphasis—" I have no hesita- tion in declaring, that I hold myself bound in honour and conscience, and pledge myself to act on the principle of the resolution adopted by the House Qf Contntons."

The Marquis of LONDONDERRY said that he was intrusted with a petition signed by sixty thousand inhabitants of the North of Ireland, praying for protection to the Church, which was now threatened on every side— It was impossible to see who was placed at the head of the Home Depart- ment without knowing that Ireland woald be convulsed to its foundations. He should take the opportunity of the earliest day after the recess to present this petition. He had hitherto refrained from presenting it, as he felt convinced that the conduct of the late Government would have afforded consolation to Ire- had; but as he now found it likely to be the contrary, he should discharge his duty to those who had intrusted bun with this petition. If Lord Melbourne went on in this way, he would be carrying on his Government by the positive forbearance of the Conservatives on the or: ' 'd and the delusive promises to the O'Connell party on the other. He m. ii iy ask the Marquis of Lans- downe whether such a Government was competent to govern the country ; he might do this as the noble marquis had done it to him ; but he should follow a different course from the noble marquis, and not quarrel with their incompe- tency till it was exhibited. They had seen an opportunity of that, for since the declaration that bad been made of no agreement whatever with Mr. O'Connell —of a positive veto, a positive exclusion against Mr. O'Connell and his Radical crew—his Radical Tail would soon show bow little Lord Melbourne's Govern- ment had to depend on.

Lord TEYNHAM called Lord Londonderry to order : he was not speaking with proper respect of the House of Commons.

Lord LONDONDERRY wished to treat the House Of COMMONS with respect. He had bowed to a decision of that House ; but he did say, and be distinctly declared, that the section of the House of Commons which he had called the Radical Tail, was the greatest curse to the country.

Lord MELBOURNE observed- " The noble marquis has put words into my mouth which I did not use. I did not say one word about a veto or an exclusion. I said that I had taken no means to secure the aid of Mr. O'Connell, and that I had made no terms with aim. As to veto,' or 'exclusion,' they are words which I should be very sorry either to use or acknowledge."

It was then agreed, that the House should adjourn to the 30th April, but that no public business should be proceeded with till the 12th of May. The House of Commons presented a singular appearance ; for Sir Robert Peel having taken his seat on the Opposition benches, the sup- porters of the late Ministry crossed over to the same side of the House, which was crowded by a "miscellaneous assemblage" of Whigs, Radi- cals, and Tories, leaving the benches on the right of the Speaker almost empty. A few of the" Stanley Section," however, retained their old position. About half-past four, Mr. F. T. Baring entered the House, and took his seat on the Treasury bench. The Reformers, including Mr. O'Connell and his Irish colleagues, then went over to the Minis- terial side of the House, amidst loud cheering.

Mr. BARING moved that new writs be issued for the following places. For Devonshire, in the room of Lord John Russell, who had accepted the office of Secretary of State f w the Home Department.

For the borough of Cambridge, in the room of Mr. T. Spring Rice, who bad accepted the office of Chancellor of the Exchequer. For Northumberland, in the room of Viscount Howick, who had accepted the office of Secretary at War.

For Nottingham, in the room of Sir John Cam Hobhouse, who had accepted the Presidentship of the Board of Control.

For Manchester, in the room of Mr. Poulett Thomson, who had accepted the Presidentship of the Board of Trade. For Edinburgh, in the room of Sir John Campbell, who had accepted the office of Attorney. General.

For Penryn and Falmouth, in the room of Mr. R. M. Rolfe, who had accepted the office of Solicitor-General.

For Kirkcudbright, in the room of Mr. Cutler Fergusson, who had accepted the office of Judge- Advocate.

For Totness, in the room of Lord Seymour, who had accepted the office of Lord of the Treasury. For Newport, in the room of Mr. W. H. Ord, who had accepted a similar office.

For Stirling, in the room of Viscount Dalmeny, who had accepted the office of Lord of the Admiralty.

For Clackmaanan, in the room of Admiral Adam, who had accepted a similar office.

For the Elgin District of Burghs, in the room of Colonel Leith Hay, who bad accepted the office of Clerk of the Ordnance. For Leith, in the room of Mr. J. A. Murray, who had accepted the office of Lord Advocate.

For Dundee, in the room of Sir Henry Parnell, who had accepted the offices of Treasurer of the Navy and Paymaster of the Forces. For Cashel, in the room of Mr. Sergeant Perrin, who had accepted the office of Attorney-General for Ireland.

For Dungarvan, in the room of Mr. Michael O'Loughlin, who had accepted the office of Solicitor-General for Ireland.

[Mr. Baring read this motion for " Mr. Sergeant O'Loughlin ;" when Mr. O'Connell excited a laugh in the House by saying " not Sergeant, but Michael."3

The House then adjourned to Monday, with the understanding that a further adjournment would take place to May 12th.

On Monday, the House met again ; and Mr. F. T. BARING was about to move the issue of more writs, when Colonel SIBTHORPE protested against an adjournment for so long a time as to the 12th of May ; and was about to address the House on the subject ; but The SPEAKER said, that the matter ought to be deferred till the writs had been moved for.

Writs were then ordered for the following places.

For the county of Inverness, in the room of Mr. Charles Grant, who had ac- cepted the office of Secretary of State for the Colonies. For the West Riding of Yorkshire, in the room of Lord Viscount Morpeth, who had accepted the office of Steward of the Chiltern Hundreds. [Mr. Baring stated that it was necessary to shape this motion so, as it had been im- possible to snake out in time the noble lord's appointment as Chief Secretary for Ireland.]

For the borough of Taunton, in the room of Mr. Henry Lahouchere, who had accepted the office of Vice•President of the Board of Trade and Master of the Mint.

For the Haddington Burghs, in the room of Mr. R. Steuart, who had been appointed one of the Lords of the Treasury.

i For the town of Berwick-upon- Tweed, n the room of Sir R. Dunkin, who had accepted the office of Surveyor-General of the Ordnance. For the borough of Sandwich, in the room of Sir '1'. Troubridge, who hail been appointed one of the Lords of the Admiralty.

Mr. BARING moved that the House should adjourn to the 12th of May ; and explained that it was necessary, in order to allow time for the reelection of the new Ministers, that the adjournment should ex- tend to that day. The period was not unusually long.

Colonel SIBTHORPE say no reason why he should not persist in his objection.

Mr. Baring had stated truly that those gentlemen would require time for making their arrangements ; but he would tell them that they would require, not three weeks, but as many months, before they would be what Colonel Sib- thorpe called " comfortable in their offices,"—(Laughter)—and before they could enter and sit upon their new, and as he trusted they would always be to them, thorny seats. Many months would elapse before that could take place; and he hoped in the meanwhile, they would be obliged to give way to men who would afford more satisfaction to the country. When he looked at the gracious speech of his Majesty from the Throne, which promised so much relief to the agricultural interests—(Ironical cheers from the Treasury benches)—when he looked also at the state of trade, which was never so bad, for you could not go into the City of London without hearing continual complaints on the subject,— when he saw agriculture without hope, and trade without support,—whea he looked forward to a renewal of the grand fructifying system of the new President of the Board of Trade (but who, he hoped, would not long occupy that office), —when he looked forward to the opening of the [Kam, and the inundating of the country with foreign corn,—when he saw those twenty-three gentlemen now going to enter the lists like racing horses, but not like horses of true mettle, but like splintered, spavined, brokenwinded, racers—( Great laughter)—with not a single sound one amongst them,—when he saw such a state of things,— when he saw the country in such a condition, he thought it was a hopeless ease; and his sense of duty to his constituents and the public induced him to protest against a motion in every respect so unjustifiable. When, too, he read the state- ments he did in the newspapers, he would not accuse any man of telling an un- truth, but this he would say, that he never could, and that he never would believe, that Mr. O'Connell would have held up his hat the other evening

would have put on those happy smiles, and that pleasing countenance lie then assumed, and would have stepped forward to correct Mr. Baring in moving one of the new writs—if he had not been a prompter and adviser in the things that

had taken place. He had another objection to the proposed adjournment, as it would again oblige him to put off a motion that he had frequently endeavoured

to bring in for the appointment of a select committee in reference to the Eccle-

siastical Courts Bill. He was no party man ; he had never acted from party feelings, but be must say that be did not like the countenances of the gehtlemen opposne—(.2hfuch laughter)—for he believed them to be the index of their minds. ( Continued laughter.) He should therefore, upon principle, oppose them upon every point ; being firmly convinced that they could do nothing to satisfy the people, to benefit the country, or to promote the dignity of the Crown; and he would only say, in conclusion, that he earnestly hoped that God would grant them a speedy deliverance from such a band. (Laughter.) Mr. O'CONNELL rose from the Ministerial side of the House, and was received with marked attention. He said— He much admired the good-humour and gentlemanly politeness which the gallant Colonel had displayed in his effective speech. (Loud laug).ter.) He did not, however, see that the countenances of the gentlemen on the Ministe- rial benches were so very much more remarkable than the gallant Colonel's own. ( General shouts of laughter.) He would not bate the gallant Colonel a single hair—( Continued laughter)—in point of good-humour. It was pleasant to have these little matters discussed in the good temper and with the politeness which characterized the gallant Colonel. Elsewhere, they might be treated in a different style, and with perfect impunity too. Elsewhere, men degraded by the resolusion of that House as unfit to hold office, might presume to talk of the Irish Representatives in a manner highly unbecoming any man, and ex- ceedingly indecent on the part of the member of an august assembly—an inde- cency that would be insufferable if it were not ridiculous. (" Hear, hear! from several Irish Members.) There was no creature, half idiot, half ma- niac, it would seem, elsewhere, that did not think himself entitled to use lan- guage there which he knew he would not be allowed to use in other places. The bloated buffoon too, who had talked of them as be did, might learn the distinction between independent men and those whose votes were not worth purchasing, even if they were in the market. He thanked the gallant Colonel for the good-humour with which he bad introduced this matter ; and if they would not have him as a friend, it was pleasant to have him as an enemy.

Mr. SINCLAIR regretted that the good-humour which Mr. O'Connell had commended bad not been exhibited by himself, when speaking of individuals in another place— He had always admired the determination of Mr. O'Connell to avoid a hostile collision with any individual. He thought he was right in that deter- munition ; but he must add, that any one who had taken such a resoiution should be peculiarly circumspect in talking of the characters of others. Ile had refrained from making any observations as to the structure of the Minis- terial edifice until they had the whole of it before them in all the symmetry of its proportions. (A laugh.) Now that it was completed, without going into its details, which he must say neither promised stability nor evinced intelli- gence, he was ready, to acknowledge that consummate dexterity and admirable discretion had been displayed, not certainly as regarded the choice, but as re- garded the exclusion of individual materials. It was a subject of no small astonishment to many, that they did not see in the front of the edifice the colossal column of granite from the Giant's Causeway. ( Great laughter.) A Member on the Ministerial side rose to order. He did not see what the Giant's Causeway had to do with the subject before them. Did Mr. Sinclair allude to the Doric column he spoke of the other night ? Mr. SINCL A IR resuming said, that he thought, with regard to the said co- luum—( Renewed laughter)—that if they cotdd dig a trench deep enough to reach the foundation of the edifice, they would find that the corner-stone of the whole building was composed of that material, and that if it were removed the whole fabric would fall to the ground. They had the ruins of the late Govern- ment before them, admirable as it was in its proportions, and crowned by a splendid and towering head. The real friends of the country deplored its de- struction ; and amongst them he supposed he might reckon a noble viscount, who, though he had just accepted office, had on one occasion told them that the dissolution of the late Government would be a misfortune. That noble viscount might now, like Marius amid the ruins of Carthage, seat himself amid the storied urns and fallen columns of the late Government, and vent his sorrows and deplore its dissolution; unless, indeed, office and place might supply a soothing anodyne to his pain. In whatsoever light they viewed him, he would as.ert that no man could stand in a higher situation, with a more unblemished cha. racter, or a more established reputation than the late Chancellor of the Exche.. quer. He had displayed a zeal in the public service beyond all praise, an integrity never surpassed, a talent which no difficulties could repress, and an eloquence which no exertions could extinguish. In offering this tribute of praise to the late efforts of Sir Robert Peel, he was sure that he only spoke the sentiments of nine-tenths ef the community. With regard to the present state of affairs, he must say that he very much feared that the new Government would find it difficult to steer its course between the Radical reefs of Scylla on the one hand, and the Conservative quicksands of Charybdis on the other. (,* Hear, hear !" front the Opposition, and laughter from the Ministerial benches.) They would find it a difficult task to make their way through without being stranded ; for they were likely to do enough to alarm the Conservatives, and too little to satisfy the Radicals. The consequence, therefore, as it appeared to him, would be that they were likely to witness on some future day—a day that could alone be foretold in Moore's Almanack—a conjunction between the Wel- lington Mars and the O'Connell Jupiter, with all his satellites: and that a mo- tion that the country bad no confidence in Ministers would be made in that House by Sir Edward Knatehbull—(" Order, order !")—he begged pardon, by the honourable baronet the Member for Kent, which motion would be seconded by Mr. O'Dwyer, not the Member for Drogheda, and carried by 420 against 198, thus giving a considerable majority for the question. With regard to the present rootiln, he had not the slightest objection to the proposed adjournment to the 12th of May. Indeed, he thought such an interval of repose from their past labours was absolutely required to fit them for their future exertions.

The House then adjourned to May 12th.

Limn Cituacit. On Monday, Mr. SIIEIL gave notice, that on the first day of going into Committee of Supply, he would move a reso- lution to this effect—that no person who should hereafter be appointed to and enter upon an ecclesiastical benefice in Ireland, should be deemed to have:a vested interest in it, entitling him to compensation in the event of its being suppressed.l;

Sir R. Isnus rose, and with a good deal of warmth, said that he also begged to give notice, that on Mr. Sheil's making that motion, be would move that the oath which Mr. Shell had taken should be read. (Greet chccriegfrom the Opposition.)

Previous page

Previous page