BRIDGE

Pessimism pays

Susanna Gross

HAVING a pessimistic nature is a great advantage if you're a bridge player. Experts never play a hand without first asking: `What can possibly go wrong?' They imag- ine that every suit will break badly, that every finesse will fail, that every card will be badly placed — and then try to work out whether they can still make their contract. Naturally, they succeed far more often than the optimistic types who presume luck will be on their side.

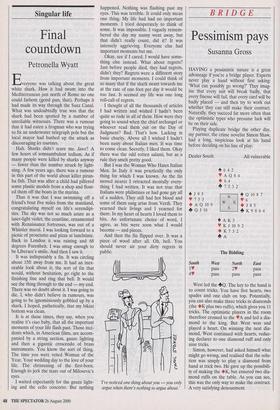

Playing duplicate bridge the other day, my partner, the crime novelist Simon Shaw, had a long, suspicious look at his hand before deciding on his line of play: Dealer South All vulnerable 4 6 4 2

♦ A Q 8 4 ♦ 6 4 # 7 5 3 2

# J 9 5 VP 7 5 3

♦ A Q 10 9 • Q J 10

N

W E S 4 Q 10 8 7 • 6 ♦ 1 8 5 • K 9 8 6 4

+ A K 3

✓ K J 10 9 2

♦ K 7 3 2 # A

The Bidding South West North East 1V pass 2V pass 4, pass pass pass West led the 40. The key to the hand is to count tricks. You have five hearts, two spades and one club on top. Potentially, you can also make three tricks in diamonds (the •K plus two ruffs), which gives you 11 tricks. The optimistic players in the room therefore crossed to the VA and led a dia- mond to the king. But West won and played a heart. On winning the next dia- mond, West continued with hearts, reduc- ing declarer to one diamond ruff and only nine tricks.

Simon, however, had asked himself what might go wrong, and realised that the solu- tion was simply to play a diamond from hand at trick two. He gave up the possibili- ty of making the ♦K, but ensured two dia- mond ruffs on the table. As you can see, this was the only way to make the contract. A very satisfying denouement.

Previous page

Previous page