ENDPAPERS

Le Shopping

By LESLIE ADRIAN

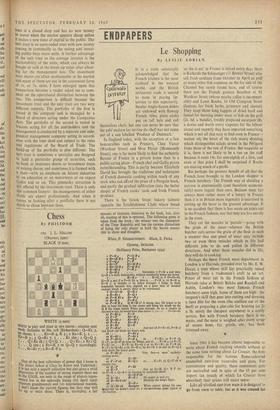

In England today, with,the exception of a few honourables such as Pruniers, Chez Victor (Wardour Street) and Mon Plaisir (Monmouth Street), one is far more likely to find the authentic flavour of France in a private home than in a public eating place—French chef and Gallic prices notwithstanding. This is partly because Elizabeth David has brought the traditions and techniques of French domestic cooking within reach of any cook who can afford the price of a Penguin book, and partly the gradual infiltration (into the better shops) of French cooks' tools and fresh French produce.

There is the Greek Street bakery (almost opposite the Establishment Club) where bread

'as she is eat' in France is baked every day; there is Richards the fishmonger (11 Brewer Street) who sell fresh sardines from October to April as well as many other fish common on the far side of the Channel but rarely found here; and of course there are the French grocers Bourbon at 81 Wardour Street (whose mocha coffee is incompar- able) and Louis Roche, 14 Old Compton Street (famous for fresh herbs, primeurs and cheese). They keep those long faggots of dried basil and fennel for burning under meat or fish on the grill (2s. 6d. a bundle), freshly prepared escargots (8s.

a dozen and worth every sixpence for the labour alone) and recently they have imported something

which is not all that easy to find even in France—

walnut oil, the heart of the rich meaty dressing which distinguishes salads served in the Perigord from those of the rest of France. But exquisite as it is, there is not likely to be a run on the stuff because it costs 14s. for one-eighth of a litre, and even at that price I shall be surprised if Roche are making much of a profit.

But perhaps the greatest benefit of all that the French have brought to the London shopper is French butchery. The French way of dividing a carcase is anatomically (and therefore economi- cally) more logical than ours. Because meat has always been rather more of a luxury in France than it is in Britain more ingenuity is exercised in Cutting up the beast to the greatest advantage. It is no accident that there is less waste on joints cut in the French fashion, no that they are less unruly in the oven.

They cut the muscles in 'parcels'—going with the grain of the meat—whereas the British butcher cuts across the grain of the flesh in such a manner that one piece of meat may include two or even three muscles which in life had different jobs to do and pulled in different directions. And what those muscles did in life, they will do in cooking.

Perhaps the finest French meat department in London is at Harrods, presided over by Mr. E. W.

Ducat, a man whose skill has practically raised butchery from a tradesman's craft to an art. Prices of meat cut in the French fashion at Harrods (also at Benoit Bulcke and Randall and Aubin, London's two most famous French butchers) seem high. Some of them are high: the surgeon's skill that goes into cutting and dressing

a faux filet for the oven (the costliest cut of the beef) or preparing a plat-cote for braising (at 2s a lb. surely the cheapest anywhere) is a costly service. But with French butchery there is no waste, and the meat is weighed after every scrap' of excess bone, • fat, gristle, etc., has bech trimmed away.

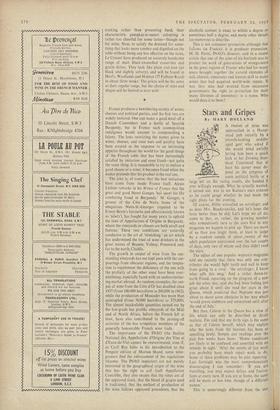

Since 1961 it has become almost impossible to write about French cooking utensils without at the same time writing about Le Creuset, the firm responsible for the famous flame-coloured enamelled cast-iron casseroles and pans. For convenience and quality, these convenient pots are unrivalled and in spite of the 15 per cent import tax (much of which Le Creuset have absorbed) their prices still make sense.

Like all vitrified cast-iron ware it is designed to go from oven to table, but as it was created for

cooking rather than presenting food, their characteristic pumpkin-at-sunset colouring is rather too cheerful for some tastes—though not for mine, Now, to satisfy the demand for some- thing that looks more sombre and dignified on the table without being any less effective on the stove, Le Creuset have produced an austerely handsome range of matt black-enamelled casseroles and gratin dishes. They look like plain cast-iron (jet black and slightly velvety), and will be found in Heal's, Woollands and Habitat (77 Fulham Road) in about three weeks. The prices will be the same as their regular range, but the choice of sizes and shapes will be limited to start with. • France produces a bewildering variety of wines, cheeses and political parties, and the first two are widely imitated. One can make a good meal off a Danish Camembert and a bottle of Spanish Burgundy, but in France such cosmopolitan indulgence would amount to compounding a felony. The laws restricting the names given to wines, cheeses, and even nuts and poultry have been created as the response to an increasing appetite throughout the world for the good things of the French table that has been increasingly satisfied by imitation and even fraud—not quite the same thing. It is reasonable to try to imitate a good cheese or a wine; it becomes fraud when the maker pretends that his product is the real one.

The joke is, of course, that the best imitations have come from inside France itself, Alexis Lichine remarks in his Wines of France that the great and good Henri Gouges 'ha's spent his life combating fraud in Burgundy.' M. Gouges, a grower of the C8te de Nuits, home of the ubiquitous Nuits-St.-Georges (reputed to be Ernest Bevin's favourite and affectionately known as 'newts'), has fought for many years to uphold the laws of Appeliations d' Origine in Burgundy, where the vineyards or climats are both small and famous. These two conditions are naturally conducive to the art of 'stretching,' an art which has undermined the trust of wine drinkers in the great names of Beaune, Volnay, Pommard and, far to the north, Chablis.

The growth in output of wine from the out- standing vineyards has not kept pace with the out- pourings from obscurer regions, and the tempta- tion to supplement the deficiency of the one with the prolixity of the other must have been over- whelming, especially faced with an undiscriminat- ing market abroad. As random examples, the out- put of wine from the Cate d'Or has doubled since 1937 (from 100,000 hectolitres to 200,000 in 1962), while the production of Muscadet has more than quintupled (from 70,000 hectolitres to 375,000). The almost incalculable quantities turned out by the low-grade but prolific vineyards of the Midi and of North Africa, before the French left at least, have also contributed to the passing-off activities of the less scrupulous members of the generally honourable French wine trade.

The importance of the INAO (the Institut National des Appellations d'Origine des Vins et d'Eaux-de-Vie) cannot be overestimated, even if, as Cyril Ray hints in his introduction to the Penguin edition of Morton Shand, some wine- growers find the enforcement of the regulations irksome. The INAO inspectors are not merely interested in the geographical origin of the wine that has the right to call itself Appellation Controlde, they also ensure that the vines are of the approved stock, that the blend of grapes used is traditional, that the method of production of the wine follows approved precedents, that the alcoholic content is exact to within a degree or sometimes half a degree, and many other details too numerous to describe.

This is not consumer protection, although that follows (in France); it is producer protection. M. H. Pestel, INAO's director, said in a recent article that one of the aims of his Institute was to protect the work of generations of winegrowers in the great regions of France who had for many years brought together the natural elements of soil, climate, vinestocks and human skill to make wines that had acquired world-wide repute. It was they who had wrested from successive governments the right to protection for their many lifetimes of investment in a name. Who would deny it to them?

Previous page

Previous page