GROUNDED CHICKENS

Vicki Woods finds the

airports empty as American civilians hide from the war

THE HAUTE couture collections taking place in Paris next week will be sparsely attended, especially by Americans. Don't you know there's a war on? Many Amer- ican fashion editors won't be attending, nor fashion buyers, nor the superstar American models — the six-foot, mostly blonde 19- and 20-year-olds with bee-stung lips and beautiful skin and big` wide eyes who say, 'We don't get out of bed for less than $10,000 a day.'

Americans are notoriously windy travellers. In contrast to their gung-ho F-111 pilots who are kicking Saddam's ass in the Gulf, American civilians have yielded superiority in the air. They won't fly to Paris. They won't fly to Europe, in fact. Nor to Thailand either, nor Australia, nor the Philippines, and some of them are even getting a bit leery about shuttling to O'Hare or Dallas, Fort Worth, for fear of Abu Nidal and the Nidalites.

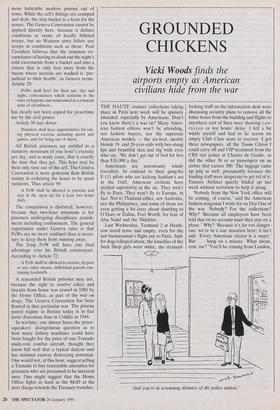

Last Wednesday, Terminal 2 at Heath- row stood tense and empty, even for the last businessman's flight out to Paris. Snif- fer dogs lolloped about, the knuckles of the Sock Shop girls were white, the strained-

looking staff on the information desk were discussing security plans to remove all the letter boxes from the building and flights to anywhere east of Suez were showing CAN- CELLED or ten hours' delay. I felt a bit windy myself and had to lie across six empty Club Class seats to recover. I got three newspapers, all the Tissus Citron I could carry off and VIP treatment from the CRS riot police at Charles de Gaulle, as did the other 30 or so passengers on an airbus that carries 300. The luggage came up pdq as well, presumably because the loading staff were desperate to get rid of it. Eastern Airlines quietly folded up last week without terrorism to help it along.

`Nobody from the New York office will be coming, of course,' said the American fashion magazine I write for on Day One of the war. Nobody? For the collections? Why? 'Because all employees have been told that on no account must they step on a plane.' Why? 'Because it's far too danger- ous; we're in a war situation here; it isn't safe. Every American citizen is a target.' But . . . hang on a minute. What about, erm, me? 'You'll be coming from London, And you're in screaming distance of the police station.' of course. Not from New York.' But I'm a British citizen. I'm a target, too. I mean, we're allies and everything. (Brief pause.) `Have you considered coming by train?' Oh, look, this is mad. I can't believe nobody's going to come from America. What about seeing the clothes? 'Oh, they can have videos sent to New York.' By carrier pigeon? 'No, by Federal Express.' You mean, parcels can fly but people can't? But Federal Express has people, too; flying the planes. 'Listen, we're talk- ing about key personnel here. The com- pany has to be responsible for their safety.'

There's something about the Americans that differs wildly from me and thee. My neighbour the headhunter was due to hold his annual board meeting in Frankfurt. He had to cancel it when the American contin- gent squealed about travelling to Europe. 'Bit windy, the Americans.' We reflected on windiness, and how Sylvester Stallone cancelled his visit to promote Rocky IV (or whichever it was) at the Cannes Film Festival in 1987 because Mr Reagan, to the fury of Kate Adie, had bombed my old school (it was in the Azizia Barracks in Tripoli, which is now home to Mr Gadda- fi). That was the summer no Americans came to London, in case Abu Nidal and the Nidalites got to them. `The coward dies a thousand times; the hero only once.' Though once is enough, I suppose. Mr Stallone may now reflect that events proved him absolutely right about ducking the Cannes Film Festival because he is still very much with us. But so, I imagine, is every single other star who turned up at Cannes that year, barring the odd cardiac arrest from too much cocaine. Americans are scared of living and scared of dying. You can't cook breakfast for an American house guest without inducing timor mortis. You see prime Suffolk bacon and eggs and sausages, and they see cholesterol (death), saturated fatty acids (death) and high levels of sodium (death). You can't buy champagne in America without the Surgeon-General reminding you not to point the cork towards your eye: It May Be Dangerous To Your Health (blinding followed by death). The Rayburn in my kitchen could not be sold in America, because the handles on the oven doors get hot. I use an oven glove, but the American housewife is protected by Federal law and a four-inch wooden handle from having to work out that anthracite can reach a temperature of 400°F in 20 minutes (severe burning and possibly death).

How does a nation like this ever raise an army? And, having raised it, how does it let it overseas to chew gum, kick ass and bomb the bejasus out of Baghdad? Stor- min' Norman Schwarzkopf looks like a robust sort of a bloke to me. Does he stick to a low-cholesterol diet? And why is it that the American army is encouraged to display the sort of maty truculence that stiffens the nerve at this frightening time, while the civilian population is expected to jib and panic and cancel their flights? Sylvester Stallone never hid the fact that he was petrified to fly to Cannes. Americans don't mind admitting that they're panick- ed. I suppose that makes them a sensible people with wonderful parenting strengths CI should get on a plane that some maniac wants to blow up? Leave my kids father-

less?' and so forth). But mass panic is a terrible thing to let loose, and it is genuine- ly odd that an entire nation should be paralysed with fear because of the minute statistical probability that a Nidalite will get some scores of them.

I'm remarkably scared of dying myself, as a civilian mother of half-grown children. I am as morally hoist as any other former peace marcher about whether or not it's a Just War, and I can panic as well as anybody if I see an untidily parked car outside Harrods or a sweating air hostess; but it's too late to get out of it now. I watched a British nurse this morning on television saying yes, she was scared up here at the front line but, 'If your number's up, it's up. You can't spend every minute worrying about it.'

One doesn't want to sound like a Sun editorial, or Mrs Miniver, but shouldn't we carry on flying and to hell with it? The pilots and cabin staff and loaders still have to get the planes out. I know absolutely that terrorist bombs will come, but I can't know absolutely either that they will or they won't get me. Who can hope to avoid a random fate or 'the inescapable will of God' to quote King Fand. 'I was thinking about driving across,' said a fashion editor I know. Well, I'm going back this week and I'm not thinking about driving across, or getting the train across. I'll damn well keep flying across, and I hope to find lots of Kenneth More types sitting in the airport lounge, making jokes through their stiff upper lips. By Day Five of the war the beauteous (and British) editor of my American had booked her ticket too. Are we downhearted? No.

Previous page

Previous page