IT'S YOUR MOVE, PEKING

Chris Patten tells Dominic Lawson what

he thinks of China's negotiating tactics in the battle over the political future of Hong Kong

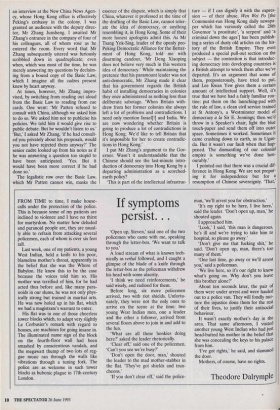

`One of these busi- nessmen even threat- ened to shoot me,' Mr Patten told me last week. But he is monumentally unruffled. 'These self- serving Cassandras have been proved hugely wrong. The Hong Kong stock-market is up 30 per cent since I put for- ward my proposals in October. Of course, I Can understand that some businessmen think that, if they want to do some deals in China, it does them no harm to badmouth the Governor. And surprisingly few of them understand the relationship between Hong Kong's prosperity and the rule of law. And they don't understand that part of the rule of law is a free press and a credible legislature. But many of these same people, In the last year or two before the 1997 han- clover, will be knocking on my door saying, What guarantees have you got that the Chinese will behave as they say they will in the Joint Declaration? What are you going to do about the rule of law after 1997, Mr Patten?"'

But for all the Governor's confidence — and he does not look at all like a worried man — there are signs that his patron in Downing Street is losing patience with the political deadlock over Hong Kong. Since April, when the Chinese finally agreed to discuss the colony's electoral arrangements, there have been five rounds of Sino-British talks. On each occasion the British delega- tion has left Peking (the Chinese only play home matches) with next to nothing. Now John Major has recalled Chris Patten to London, for a meeting on 1 July of the Cabinet's Hong Kong Committee, to decide whether there is any point in contin- uing the dialogue of the deaf with Peking. `There are those,' Mr Patten told me wearily, the day after the fifth round of talks had ended, 'more accustomed than I to negotiating with the Chinese, who think that they are moving, but it's not like nego- tiating with any other country.' He rolled his eyes. 'It requires the patience of the aeons.'

China insists that Mr Patten's proposals for the widening of the franchise for the next elections to the Hong Kong Legisla- tive Council infringe the Basic Law, the Chinese statute that will govern the 'Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China' after 1997. Mr Patten, to their fury, quotes back at them chapter four, section three of the Basic Law: `The ultimate goal is the election of all the members of the Legislative Council by universal suffrage.' The Chinese then quote in return Article 158, which states: `The power of interpretation of the Basic Law shall be vested in the Standing Com- mittee of the National People's Congress.' In other words: we decide what the Basic Law means, not you. And so it has gone on for months.

In the relative sanity of his office at Gov- ernment House, Mr Patten hilariously describes the Had I, too, not had an encounter with the officials of the Chinese foreign service the day before, I might have thought that Mr Patten was exaggerating. I had sought an interview at the New China News Agen- cy, whose Hong Kong office is effectively Peking's embassy in the colony. I was granted an audience with the deputy direc- tor, Mr Zhang Junsheng. I awaited Mr Zhang's entrance in the company of four of his colleagues, all of whom rose as he entered the room. Every word that Mr Zhang subsequently uttered was furiously scribbled down in quadruplicate; even when, which was most of the time, he was merely answering my questions by declaim- ing from a bound copy of the Basic Law, which I imagine all the cadres present knew by heart anyway.

At times, however, Mr Zhang impro- vised, by switching from reading out aloud from the Basic Law to reading from cue cards. One went: 'Mr Patten refused to consult with China, although we asked him to do so. We asked him not to publicise his policies. We told him it would give rise to public debate. But he wouldn't listen to us.' `But,' I asked Mr Zhang, 'if he had consult- ed you privately about his proposals, would you not have rejected them anyway?' The senior cadre looked up from his notes as if he was answering a question too stupid to have been anticipated. 'Yes. But it would have been more correct if he had done so.'

The legalistic row over the Basic Law, which Mr Patten cannot win, masks the essence of the dispute, which is simply that China, whatever it professed at the time of the drafting of the Basic Law, cannot toler- ate the idea of democracy, or anything resembling it, in Hong Kong. Some of their more honest apologists admit this. As Mr Tsang Yok-Sing, leader of the openly pro- Peking Democratic Alliance for the Better- ment of Hong Kong, told me with disarming candour, 'Mr Deng Xiaoping does not believe very much in this western idea of democracy.' While maintaining the pretence that his paramount leader was not anti-democratic, Mr Zhang made it clear that his government regards the British habit of installing democracies in colonies they once administered as nothing less than deliberate sabotage. 'When Britain with- drew from her former colonies she always left a lot of problems and contradictions. I need only mention Israelr I and India. We are now wondering whether Britain is going to produce a lot of contradictions in Hong Kong. We'd like to tell Britain that it's impossible for her to create contradic- tions in Hong Kong.'

I put Mr Zhang's argument to the Gov- ernor. Wasn't it understandable that the Chinese should see the last-minute intro- duction of democracy into Hong Kong by a departing administration as a scorched- earth policy?

`This is part of the intellectual infrastruc- ture — if I can dignify it with the expres- sion — of their abuse. Wen Wei Po [the Communist-run Hong Kong daily newspa- per which has variously called the 28th Governor 'a prostitute', 'a serpent' and 'a criminal down the ages] has been publish- ing a series of dusty old articles on the his- tory of the British Empire. They even produced a special pull-out section on the subject — the contention is that introduc- ing democracy into developing countries is a British attempt to wreck them after we've departed. It's an argument that some of them, preposterously, have tried to put, and Lee Kwan Yew gives them a certain amount of intellectual support. Well, it's true that we have had a fairly familiar rou- tine: put them on the launching-pad with the rule of law, a clean civil service trained at St Antony's, a Westminster model of democracy a la Sir E. Jennings; then we'd throw in a Speaker's chair, light the blue touch-paper and send them off into outer space. Sometimes it worked. Sometimes it came crashing down to earth, as in Ugan- da. But it wasn't our fault when that hap- pened. The dismantling of our colonial empire is something we've done hon- ourably.'

I pointed out that there was a crucial dif- ference in Hong Kong. We are not prepar- ing it for independence but for a resumption of Chinese sovereignty. 'That; said Mr Patten, 'does not make it any the less honourable an enterprise.'

That is not altogether the view of Martin Lee, the leader of the United Democrats of Hong Kong. China is far more scared of Mr Lee than it is of Mr Patten. It was Mr Lee's courage that brought out one million people in protest onto the streets of Hong Kong on the day after the Tiananmen mas- sacre. It was Mr Lee's party that swept the board in what passed for elections in Hong Kong in 1991. It is Mr Lee's party that, the Chinese fear, will take control of the Hong Kong legislature if the franchise is widened. In Peking's eyes, that is tanta- mount to Hong Kong's being taken over by subversives.

I arranged somewhat tactlessly to meet Mr Lee at the exotic China Club, a remark- able celebration of communist kitsch and cuisine on the 13th floor of the Bank of China building, from where, at the height of the cultural revolution, Bank of China employees shouted down on the people of Hong Kong to overthrow the Governor. almost refused to meet you here,' said Mr Lee, casting his eyes over such glittering attractions as 'The Long March Bar'. Mr Lee cannot understand why Mr Patten, having announced his proposals last November, has still not presented them to the Legislative Council, and instead has kept Hong Kong's fledgling parliament waiting for months while the British and Chinese foreign services attempt to come up with a diluted version of Mr Patten's democratic heresy. 'Mr Patten holds him- self as a champion of democracy in Hong Kong, and has thus gained adulation from here to Capitol Hill. How can he back down? On the other hand, how can China make huge concessions to a "prostitute"? The talks are doomed to fail.'

Mr Patten is, in fact, quite prepared to see his proposals amended. 'You could produce — I could do it now — all sorts of arrangements which would achieve the same objective of clean elections, elections that can't be rigged, that produce a credi- ble legislature, and not a rubber-stamp leg- islature. My bottom line is that whatever emerges from the talks must produce that result.'

Originally, the British set a private dead- line of July for the talks to succeed. As that deadline approaches, Mr Patten's problem becomes acute. Does he dare put his pro- posals to Hong Kong's legislators, and risk an almost certain retort from Peking that it will not recognise the new parliament when it takes over in 1997?

Mr Patten appears to be preparing for confrontation while hoping it will not come to that. `July has been mentioned as a rea- sonable time to get our legislation in place, and to prepare for free, open and fair elec- tions. I don't want our negotiators to feel contained by the calendar but plainly there comes a point beyond which you can't rea- sonably delay.'

`And what happens at that point?' `At that point we would have to carry out the responsibility of government.'

The mayhem this — pressing ahead in the teeth of China's most bloodcurdling threats — would cause could add new chapters to the colourful history of Sino- British diplomatic insults.

On the face of it, Mr Patten has no cards to play. China, as one of the members of the British negotiating team told me, 'can do whatever it likes to Hong Kong, and we can't stop them'. But Mr Patten is not entirely bluffing. He knows that any major confrontation between London and Peking would devastate the Hong Kong stock-mar- ket. And who has been the biggest single investor in that market in recent months? The Chinese government. Last week, for example, Citic, a Chinese state investment arm, bid almost HK$10 billion to take over the Hong Kong hotel company Miramar. This year alone, the Chinese government plans to float nine of its companies on the Hong Kong stock-market. Such desperately needed refinancing plans would be com- pletely scuppered by open diplomatic war between Britain and China. Quietly, almost silently, Peking's leaders have become as dependent on the financial markets as any democratically elected western govern- ment.

But all this means is that we are relying on China to put its financial self-interest ahead of its — rather horrifying — political principles. And, I asked the Governor, didn't the Tiananmen massacre show that Mr Deng's mind, however decreasingly lucid, did not work like that? 'I don't believe that history is likely to repeat itself.'

Old Foreign Office hands, such as Sir Percy Cradock, the architect of the existing Sino-British political settlement in Hong Kong, believe Mr Patten fatally underesti- mates the Chinese capacity for brutality, and that he would be acting in the best interest of the people of Hong Kong if he did not risk provoking such repression after 1997.

The mention of Sir Percy seemed to irri- tate the Governor far more than the names of any of his Communist opponents. 'I must say that the people who have been giving me this wise advice don't seem to have delivered much for the people of Hong Kong in the recent past. But I don't want to be as obsessive about Sir Percy as he seems to be about me. There is a view which some diplomats, though not the best, adhere to, that diplomacy is about using words cleverly in order to finesse matters of substance. I don't happen to believe that . . if we hadn't been prepared to stand up for Hong Kong before 1997, there was bug- ger all chance of seeing anybody stand up for it after 1997.'

After 1997. The Governor, like everyone else in the colony, is a tenant at the smoul- dering end of a burnt-out lease, at the mercy of a capricious freeholder. I left Mr Patten at his desk. On the wall behind him hangs a bleak terracotta crucifix. The wall in front of him is equally austere, decorat- ed only by a large, plain clock. If ever there was a man trapped between things spiritual and things temporal, that man is the last British Governor of Hong Kong.

'Oh, come, Travers. You're supposed to contribute to the ambience.'

Previous page

Previous page