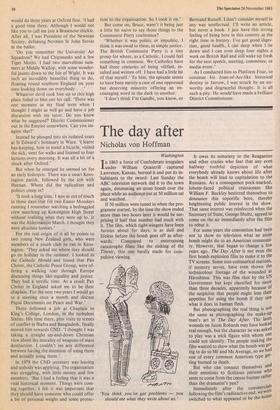

The making of a Monsignor

Pearson Phillips

e's got a speaking engagement at -11..Yarrow,' said Monsignor Bruce Kent's secretary, who is called Judy.

Yarrow? Where's that?

'In the North-East, somewhere.'

Oh. You mean Jarrow.

'Is that how it's pronounced?' That's one CND functionary who could hardly be said to be drenched in the folk-lore of the Left.

A meeting was arranged for King's Cross Station. The Monsignor's Inter-City left for Newcastle at three. 'I'll hang around the main foyer at two, then move into the Great Northern Hotel,' said his voice on my answering machine. 'We'll have an hour together. Looking forward to seeing you. Bruce.'

I was mildly apprehensive. It had been 30 years since I had found myself out- numbered two-to-one by Catholics while riding a motor-bike. I was on the back. Bruce was steering the thing. In between was an auburn-haired sport from St Hugh's called Mimi, who became Mrs Somebody- Terribly-Eminent. Had it been his idea to pick her up from the Trout Inn, or mine? It.. was a bad idea, whoever's it was. The police stopped us on the Woodstock Road. Bruce, the driver, got done for riding three up. The fact that I didn't even share the fine has been on my conscience for three decades.

'He mixed with a merry, not noticeably cerebral set of Brasenose sportsmen,' said a recent Observer profile. That was us. Odd glimpses of him filtered through in the suc- ceeding years, keeping the memory of him sharp. His appointment as Cardinal Heenan's secretary didn't surprise me. But then came an odd letter to the Times, com- plaining that he had just been bombed while standing in a marketplace in Biafra.

The latest characterisation of him as an amiable Canon Collins figure, 'a man of ex- cellent intentions, boundless faith and limited political intelligence', according to Conor Cruise O'Brien, didn't really seem to fit. It was time to refresh the acquaintance.

He sat in his smart clerical grey, braced for brisk verbal combat with what he once called 'the dark forces of misrepresenta- tion'. But I just wanted to know how it all .began. I never heard him talking about.

nuclear weapons or pacifism at Oxford. They were not subjects much discussed in the Third Boat (the 'Hearties' crew), in which he rowed number six. I don't remember detecting even a hint of him heading for the priesthood.

`No. You didn't know. Nobody knew. But I had decided before Oxford. It was quite a sudden personal experience. I'd just left the army, and went back to Stoneyhurst on what we called "an Old Boys' retreat". All Catholic schools have them. Your spiritual life is given the once-over. One of the speakers was a man called Father Joseph Christie, who was very impressive. Having listened to him I felt, well . . . how do you describe a vocation? I felt God was calling me to be a priest and that was a very strong conviction.'

His Jesuit Father may have had that message, but his own father was not even a Catholic. He was a Canadian, brought up in Montreal, where Catholics and Pro- testants were at each other's throats much as in Belfast today. 'My becoming a priest was more than he could stomach at the time.'

They were an affluent, middle-class fami- ly (his mother was a Catholic) who had ar- rived from Canada in the Twenties to start a business. I remember a luxurious, wall-to- wall-carpeted living-room in a big house in Hampstead Garden Suburb.

The agreement was that a decision on the priesthood would be postponed. Bruce would do three years at Oxford first. 'I had a good time there. Although I would not like you to call me just a Brasenose thickie. After all, I was President of the Newman Society, defeating Norman St John Stevas in the ballot.

`Do you remember the University Air Squadron? We had Chipmunks and a few Tiger Moths. I had two marvellous sum- mers at Middle Wallop, with some wonder- ful jaunts down to the Isle of Wight. It was such an incredibly beautiful thing to do, floating round southern England on your own looking down on everybody . .

Whatever devil took him up to this high place failed to blot out his call. 'There was one moment in my final term when I thought I might as well go and have a job discussion with my tutor. Do you know what he suggested? District Commissioner out in the Empire somewhere. Can you im- agine that?'

Instead he plunged into six isolated years at St Edward's Seminary in Ware. 'I learnt bee-keeping, how to mend a bicycle, visited the sick, went for walks and listened to four lectures every morning. It was all a bit of a shock after Oxford.'

But when he emerged he seemed set for an early bishopric. There was a smart Kens- ington parish, followed by the job with Heenan. Where did the radicalism and politics creep in?

'It took a long time. I was so out of touch in those days that for two Easter Mondays running I remember watching a bedraggled crew marching up Kensington High Street without realising what they were up to. It was the Aldermaston March. I thought they were absolute loonies.'

For the real origin of it all he points to two young New Zealand girls, who were members of a youth club he ran in Kens- ington. 'They asked me where they should go on holiday in the summer. I looked in the Catholic Herald and found that Pax Christi, the Catholic Peace Group, were of- fering a walking tour through Europe discussing things like equality and justice. They had a terrific time. As a result Pax Christi in England asked me to be their chaplain. For the next two years I would go to a meeting once a month and discuss Papal Documents on Peace and War.'

There followed a job as Chaplain to King's College, London, in the turbulent Sixties. His time there, plus visits to scenes of conflict in Biafra and Bangladesh, finally, moved him towards CND. 'I thought I was taking a straight up-and-down Christian view about the morality of weapons of mass destruction. I couldn't see any differencd between having the intention of using them and actually using them.'

In 1979 the CND secretary was leaving and nobody was applying. The organisation was struggling, with little money and few members. 'But I had a feeling that it was a vital historical moment. Things were com- ing together. I felt it was important that they should have someone who could offer a bit of personal weight and some protec-

tion to the organisation. So I took it on.'

But come on, Bruce, wasn't it being just a little bit naive to say those things to the Communist Party conference?

'Whether it was politic or impolitic, I think it was owed to them, in simple justice. The British Communist Party is a tiny group for whom, as a Catholic, I could feel something in common. We Catholics have had three centuries of being vilified, in- sulted and written off. 1 have had a little bit of that myself.' To him, the episode seems to have been merely a case of one oppressed but deserving minority offering an en- couraging word in the dark to another.

'I don't think I'm Gandhi, you know, or Bertrand Russell. I don't consider myself in any way intellectual. I'll write an article, but never a book. I just have this strong feeling of being here in this country at the right time in history. I've got good diges- tion, good health, I can sleep when I lie down and I can even sleep four nights a week on British Rail and still wake up fresh for the next speech, meeting, committee, or media event.'

As I conducted him to Platform Four, to continue his Joan-of-Arc-like historical destiny in Jarrow, I was struck by an un- worthy and disgraceful thought. It is all such a pity. He would have made a brilliant District Commissioner.

Previous page

Previous page