Larkin' about

Christopher Hawtree

Required Writing Philip Larkin (Faber & Faber £4.95) f I seem good, it's because everyone else is so bad,' Philip Larkin once observ- ed. 'Well, almost everyone.' Such modesty recurs in the comments about his work, providing a convenient escape from the grosser importunities of academics ensconc- ed in their air-conditioned cells. It was with similar reluctance that he appears to have written most of the pieces in this miscellany, and has now only been prevailed upon to salvage them from 'a wilderness of press cuttings' because 'some of them have begun to be quoted out of context'. It need hardly be said that it makes a far more enjoyable book than the growing number of studies produced by all those types 'in jeans and sneakers' frantically seeking tenure. The dangers of collecting journalism have been well summarised by Macaulay in a letter that discusses the practical difficulties and hasty judgments frequently inherent in such work. 'The public judges, and ought to judge, indulgently of periodical works... their natural life is only six weeks... All this is readily forgiven if there be a certain spirit and vivacity in his style. But as soon as he republishes, he challenges a com- parison with all the most symmetrical and polished of human compositions. A painter who has a picture in the exhibition of the Royal Academy would act very unwisely if he took it down and carried it over to the National Gallery.'

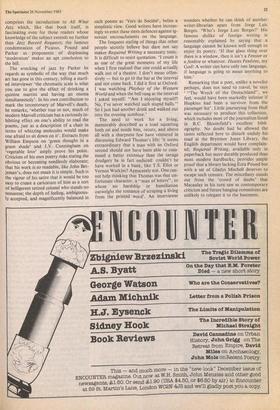

Required Writing is a book in its own right. Somewhere in the course of it Philip Larkin remarks of one biography that he read 100 pages before remembering that he should be taking some notes. So readily does each of these pieces lead to the next that the reviewer is reluctant to pause and look for a pencil. When asked whether the order of the poems in a collection is impor- tant, Mr Larkin said that he took great care over this: 'I treat them like a music-hall bill: you know, contrast, difference in length, the comic, the Irish tenor, bring on the girls...' Required Writing, too, has an un- forced and pleasing organisation, themes familiar from his poems being worked into pieces on his own life and others': the In' troduction to Jill reappears with its enter- taining description of war-time Oxford and is followed by less familiar, equally en- joyable accounts of his early time as a librarian -- it is a job, like many, that can about by chance and in which he has risen to eminence; two interviews give elegant short shrift to impertinent probings; some general observations precede the central section dealing with writers from Marvell to Fleming; half of the final part, on jazz, ' comprises the introduction to All What Jazz which, like that book itself, is fascinating even for those readers whose knowledge of the subject extends no further than Jazz Record Requests; the famous condemnation of Picasso, Pound and Parker as proponents of displeasing 'modernism' makes an apt conclusion to the bill.

The wrecking of jazz by Parker he regards as symbolic of the way that much art has gone in this century, telling a startl- ed interviewer 'the chromatic scale is what you use to give the effect of drinking a quinine martini and having an enema simultaneously'. In his own contribution to mark the tercentenary of Marvell's death, he remarks, 'whether true or not, much of modern Marvell criticism has a curiously in- hibiting effect on one's ability to read the poems, just as a description of a chair in terms of whizzing molecules would make one afraid to sit down on it'. Extracts from William Empson on 'green thought in a green shade' and J.V. Cunningham on 'vegetable love' amply prove his point. Criticism of his own poetry risks stating the obvious or becoming needlessly elaborate; that his work is so readable, like John Bet- jeman's, does not mean it is simple. Such is the vigour of his satire that it would be too easy to create a caricature of him as a sort of belligerent retired colonel who stands no nonsense; the depth of feeling, ambiguous- ly accepted, and magnificently balanced in such poems as 'Vers de Societe', belies a simplistic view. Good writers have increas- ingly to erect these stern defences against ig- norant encroachments on the language.

The frequent stating of things that other people secretly believe but dare not say makes Required Writing a necessary tonic. It is difficult to resist quotation. 'I count it as one of the great moments of my life when I first realised that one could actually walk out of a theatre. I don't mean offen- sively — but to go to the bar at the interval and not come back. I did it first at Oxford: I was watching Playboy of the Western World and when the bell rang at the interval I asked myself: "Am I enjoying myself? No, I've never watched such stupid balls." So I just had another drink and walked out into the evening sunshine.'

The need to work for a living, memorably described as a toad squatting both on and inside him, recurs, and above all with a sharpness few have ventured in discussing Edward Thomas's life: 'it seems extraordinary that a man with an Oxford second should not have been able to com- mand a better existence than the savage drudgery he in fact endured: couldn't he have worked in a bank, like T.S. Eliot or Vernon Watkins? Apparently not. One can- not help thinking that Thomas was that un- fortunate character, a "man of letters", to whom no hardship or humiliation outweighs the romance of scraping a living from the printed word'. An interviewer

wonders whether he can think of another writer-librarian apart from Jorge Luis Borges. 'Who's Jorge Luis Borges?' His famous dislike of foreign writing is reasonably explained by saying that a language cannot be known well enough to enjoy its poetry. `If that glass thing over there is a window, then it isn't a Fenster or a fenetre or whatever. Hautes Fenetres, my God! A writer can have only one language, if language is going to mean anything to him.'

Remarking that a poet, unlike a novelist perhaps, does not need to travel, he says

"The Wreck of the Deutschland", we feel, would have been markedly inferior if Hopkins had been a survivor from the passenger list'. Little journeying from Hull was necessary to produce this collection, which includes most of the journalism listed in B.C. Bloomfield's excellent bibli- ography. No doubt had he allowed the tastes reflected here to disturb unduly his toad at the Brynmor Jones Library, the English department would have complain- ed; Required Writing, available only in paperback but more durably produced than most modern hardbacks, provides ample proof that a library lacking Ezra Pound but with a set of Gladys Mitchell deserves to escape such censure. The miscellany stands out from the 'crowd of daubs' that Macaulay in his turn saw as contemporary criticism and future hanging committees are unlikely to relegate it to the basement.

Previous page

Previous page