The three weird sisters ride again

Victoria Glendinning

CHARLOTTE BRONTE by Rebecca Fraser

Methuen, f14.95, pp.543

BROTHER IN THE SHADOW: STORIES AND SKETCHES BY BRANWELL BRONTE edited by Mary Butterfield and R. J. Duckett

cheques payable to 'Bradford Council', copies available from the Administration Dept, Central Library, Prince's Way, Bradford BD1 1NN, f8 + 75p p&p, pp.153

The story of the three Brontë sisters has been told over and over again. But then so has the story of the three bears. A good story can be retold indefinitely and, pro- viding that no liberties are taken with the outline, what counts is the way it is told and the interpretation put on it. Scraps of new material continue to surface — in this case the Seton-Gordon papers, and Char- lotte's marriage settlement — and Rebecca Fraser is a lively story-teller. There is not one dull page in her book (which is the first she has written). She tends, in her vitality, to the baroque; there are some dithyrambi- cally overwrought paragraphs and a rhetor- ical flourish of an ending, viz, 'What, indeed?'

Well what, indeed? Mrs Gaskell, Char- lotte's first biographer, wrote that if the public would only see Charlotte as she really was, 'I shall feel my work has been successful'. What Mrs Gaskell wanted the public to see was Charlotte the dutiful domesticated daughter, a 'noble Christian woman' first and a gifted author second. Mrs Gaskell, a noble Christian woman herself, wanted to offset Charlotte's repu- tation as the author of irreligious, coarse and 'naughty' books. Jane Eyre, while it was avidly read, was seen by conventional moralists when it came out as offensive, even disgusting. Matthew Arnold was to condemn Villette as 'a hideous, undelight- ful, convulsed, constricted novel' by a frustrated female who ought to have sought comfort in religion.

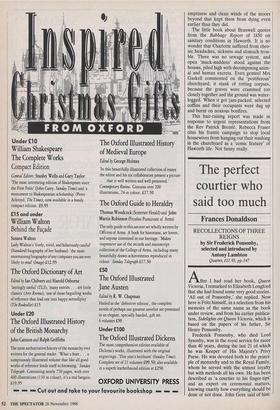

As Rebecca Fraser points out, it is hard for modern readers to understand the phenomenon that Charlotte was in her own time, or to appreciate the intense and almost prurient curiosity in the creator of Jane Eyre shown by the scribbling classes when she made her rare visits to London not to mention their amazement when faced with an undersized, undeveloped, shy, plain, almost toothless and poor- complexioned little creature in home-made frocks whose only physical attraction was her large, shining, shortsighted eyes. The late 20th century has de-romanticised the Brontës. Emily, the enigmatic genius, is characterised in this book by adjectives such as uncouth, egotistical, exacting, sharp-tongued, brusque, intractable. (Fraser might have added mentally un- stable, following Edward Chitham's recent study of Emily.) But there must have been something of Charlotte's passionate nature shining out of those eyes; two of her father's curates had proposed to her before she finally, at the age of 37 and against the wishes of her father, accepted the Rev Arthur Nicholls. Rebecca Fraser brings this long-faced, The Gun Group', 1838, one of three family group-portraits known to have been painted by Branwell Brontë. From left to right: Emily, Charlotte, Branwell and Anne. lumbering, unpopular, unpoetical curate to life, and makes the reader feel the happi- ness of the marriage — which was termin- ated in a matter of months — by Charlot- te's death.

There is so much dying in the story, and so much ill-health, depression, anxiety, poverty and self-denial for Charlotte in the Haworth parsonage, alternating with loneliness and humiliation in her spells as a governess. Charlotte Bronte's novels grew out of daydream and nightmare and thwarted desires. Fraser remarks of her despairing letters to M. Heger that how- ever full of sublimated sexuality they may be, 'their demand is actually for friendship.' What else could their demand be for? He was married. Repression was her only option.

She let herself go in the novels, but in her life and in her letters she practised and preached self-sacrifice. To this extent Mrs Gaskell was right about her. Rebecca Fraser's reading of Charlotte is a feminist one, but there is a sad irony in learning that a feminist of her own time, the doughty Harriet Martineau, hurt Charlotte's feel- ings by. disapproving of Jane Eyre's all- consuming preoccupation with love. She had a point.

Charlotte wrote Jane Eyre in a mood of depression and suppressed hysteria. Bran- well's alcoholism was by then so disruptive to ordinary life that, as Charlotte told Ellen Nussey, 'the house must now be barred to visitors.' Brother in the Shadow is the work of local historians determined to bring Branwell into the light, stressing his giftedness and creativity, not his failures: `There is no need to go into the nightmare details of Branwell's last days', nor to say more than Hello Mrs Robinson to the employer for whom he conceived a neuro- tic passion. Unlike Charlotte's obsession with M. Heger, it fuelled no works of art.

Great claims are made here for the quality of Branwell's Northangerland' writings. They seem to me unreadable by anybody except registered addicts of Bron- teiana. But while Charlotte destroyed most of the private writings of Emily and Anne, she preserved Branwell's; was this, Mary Butterfield hopefully asks, because she valued them more? If she did, I would guess it was because these fragments were absolutely all there was left of him. With heartbreaking tact, as Fraser reports, the girls had concealed the successful publica- tion of their own work from their ambi- tious, wrecked brother.

A strength of Rebecca Fraser's enjoy- able book is that she has visited all the sacred sites, and her Bronte geography comes alive. But for all her success in seeing Charlotte as her contemporaries saw her, her outward vision is 20th- century. She praises the 'pleasing, rough neo-classical simplicity' of the parsonage, the 'elegant pediment' over the door, and the 'proper garden' the children had to play in. But it was probably the bleak emptiness and clean winds of the moors beyond that kept them from dying even earlier than they did.

The little book about Branwell quotes from the Babbage Report of 1850 on sanitary conditions in Haworth. It is no wonder that Charlotte suffered from chro- nic headaches, sickness and stomach trou- ble. There was no sewage system, and open 'muck-middens' stood against the houses, piled high with decomposing anim- al and human excreta. Even genteel Mrs Gaskell commented on the 'pestiferous' churchyard; it stank of rotting corpses, because the graves were crammed too closely together and the ground was water- logged. When it got jam-packed, selected coffins and their occupants were dug up and burnt on noxious bonfires.

This hair-raising report was made in response to urgent representations from the Rev Patrick Brontë. Rebecca Fraser cites his frantic campaign to stop local housewives from hanging out their washing in the churchyard as a 'comic feature' of Haworth life. Not funny really.

Previous page

Previous page