BOOKS.

GARETH AND LYNETTE.*

To his great Arthurian building Mr. Tennyson has added the porch last, for "The Coming of Arthur," which precedes it, is not the porch, but the approach. Gareth and Lynette, which we have here for the first time, is not merely the first idyll in which King Arthur's work is seen, and that in which it is seen in its first youth and freshness, but it gives, as it should, an insight into the drift and purpose of the whole, and also forecasts the growing strength and fierceness of resistance, by which the pure kingdom of a true chivalry was to be tasked and strained. There is none of the Arthurian legends which Mr. Tennyson has more completely transformed, in mould- ing them to his own poetic purpose, than that of Gareth 'of the beautiful hands,' which occupies so great a space in the rambling story of Sir Thomas Malory, and is so full of incongruous materials awkwardly put together. To these materials Mr. Tenny- son has given a wholly new form in the idyll before us, and appearing as the immediate successor of "the Coming of Arthur," it shows us, as none of the latter idylls can show us, how

• Gareth and Lynette, and the Last Tournament. London : Strahan and Co. 1812

"The fair beginners of a nobler time, And glorying in their vows and him, his knights, Stood round him and rejoicing in his joy."

Gareth, nephew of the King, the youngest son of his half-sister Queen Bellicent of Orkney, is introduced in his vigorous youth, pining for his mother's permission to enter on the glorious enter- prises of Arthur's Knights, but dissuaded by his mother, who longs to retain her youngest son with her, and who while not denying her own belief in Arthur's divine right, puts before Gareth the doubts that men still entertain as to the rightfulness of his claim, as a reason for hesitation and delay :—he should not hazard his life, she says, for one who is not yet 'proven ' king. Thereupon Gareth, who asks no proof of a kingship which, like a higher kingship, has been revealed to him not by flesh and blood,' but by the witness of a spirit stirring in his heart, makes light of her weak dissuasions,—

" ' Not proven,' who swept the dust of ruined Rome From off the threshold of the realm, and crush'd The idolaters and made the people free ?

Who should be King, save him who makes us free ?"

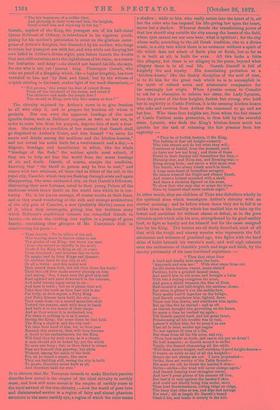

The chivalry enjoined by Arthur's vows is to give freedom to all who obey it, and to prepare for freedom all whom it protects. Nor can even the apparent bondage of the most ignoble duties, such as Bellicent imposes as tests on her son, in order to scare him from his purpose, deprive him of such a free- dom. She makes it a condition of her consent that Gareth shall, go disguised to Arthur's Court, and hire himself "to serve for meats and drinks among the scullions and the kitchen-knaves," and not reveal his noble birth for a twelvemonth and a day,—a disguise, bondage, and humiliation to which, like the whole "bondage of the flesh," the noblest spirits must submit, if they are to help set free the world from the worse bondage of sin and death. Gareth, of course, accepts the condition, knowing that "the thrall in person may be free in soul," and comes with two retainers, all three clad as tillers of the soil, to the royal city, Camelot, which they see flashing through mists and again disappearing, like some enchanted city, so that Gareth's followers, distrusting their new fortunes, retail to their young Prince all the traditions which throw doubt on the world into which he is ven- turing. He, in his joyous courage, of course mocks at their fears, and as they stand wondering at the rich and strange architecture' of the city gate of Camelot, a seer (probably Merlin) comes out of it, whom they interrogate, giving him the fictitious story which Bellicent's conditional consent has compelled Gareth to invent,—to whom the riddling seer replies in a passage of great beauty, containing clear glimpses of Mr. Tennyson's drift in constructing his poem :— " Then Garetb, 'We be tillers of the soil,

Who leaving share in furrow come to see The glories of our King : but these, my men, (Your city moved so weirdly in the mist) Danbt if the King be King at all, or come From fairyland ; and whether this be built By magic, and by fairy Kings and Queens ; Or whether there be any city at all, Or all a vision : and this music now Bath seared them both, but tell then these the truth.'

Then that old Seer made answer playing on him

And saying, SOD, I have seen the good ship sail

Keel upward and mast downward in the heavens, And solid turrets topsy-turvy in air : And here is truth ; but an it please thee not, Take thou the truth as thou hest told it me.

For truly, as thou sayest, a Fairy King And Fairy Queens have built the city, son ; They came from out a sacred mountain-cleft Toward the sunrise, each with harp in hand, And built it to the music of their harps.

And as thou sayest it is enchanted, son, For there is nothing in it as it seems Saving the King; tho' some there be that hold The King a shadow, and the city real : Yet take thou heed of him, for, so thou pass Beneath this archway, then wilt thou become A thrall to his enchantments, for the King Will bind thee by such vows, as is a shame A man should not be bound by, yet the which No man can keep ; but, so then dread to swear, Pass not beneath this gateway, but abide Without, among the cattle of the field.

For, an ye heard a music, like enow They are building still, seeing the city is built To music, therefore never built at all, And therefore built for ever."

It is obvious that Mr. Tennyson intends to make Merlin's parable describe how unreal is the empire of the ideal chivalry to earthly sense, and how still more unreal is the empire of earthly sense to the loyal servant of the true chivalry ;--how the world of pure love and disinterested service is a region of fairy and almost phantom structure to the mere earthly eye, a region of which the ruler seems a shadow ; while to him who really enters into the heart of it, alt but the ruler who has imposed his life-giving law upon the heart, seems but a shadow. Whoever dreads the transforming power of that law should stay outside the city among the beasts of the field, whose eyes cannot see nor ears hear, what is spiritual ; for the city whose walls, according to the old Greek tradition, rise to a divine music, is a city into which there is no entrance without a spirit of life which does not admit of finite plan or finish, but so far as it is built at all, is built for ever. All this looks a little like allegory, but there is no allegory in the poem, beyond what allegory there is in all real life. Gareth himself is full of knightly fire and loyalty. His humiliating probation as a 'kitchen-knave,' like the fleshly discipline of the soul of man, is to fit him for the great task which he is to accomplish in the teeth of refined scorn and aristocratic compassion for his seemingly low origin. When Lynette comes to Camelot to ask for a champion to redeem her sister, the Lady Lyonors, from the power of the four knights, foolish but strong, who holi her in captivity in Castle Perilous, it is the seeming kitchen-knave who asks and receives from Arthur the command to go and set her free. Who these four knights are, from whom the fair tenant of Castle Perilous seeks protection, is thus told by the scornful sister, Lynette, who finds the King's kitchen-knave much too ignoble for the task of releasing the fair prisoner from her captivity :— -

"They be of foolish fashion, 0 Sir King, The fashion of that old knight-errantry Who ride abroad and do but what they will ; Courteous or bestial, from the moment, such As have nor law nor king ; and three of these Proud in their fantasy call themselves the Day,- Morning-star, and Noon-sun, and Evening-star,— Being strong fools; and never a whit more wise The fourth, who alway rideth arm'd in black, A huge man-beast of boundless savagery. He names himself the Night and oftener Death, And wears a helmet mounted with a skull, And bears a skeleton figured on his arms, To show that who may slay or scape the three Slain by himself shall enter endless night."

In other words, they are children of Time who disbelieve wholly fa the spiritual aims which transfigure Arthur's chivalry with an eternal meaning ; and he before whose lance they are to fall is as- unlike them in the humility which has enabled him to take up the lowest and earthliest lot without shame or defeat, as in the pure chivalric spirit which aids his arm, strengthened by its good earthly food, to fight so loyally not for himself but for the cause assigned him by his King. The battles are all finely described, most of all that with the tough and sinewy warrior who represents the full astuteness and wiriness of practised age, who lights with the hard' skins of habit beneath his warrior's mail, and well nigh exhausts even the enthusiasm of Gareth's youth and hope and faith, by the sinewy pertinacity of his case-hardened experience :—

"Then that other blew

A hard and deadly note upon the horn.

'Approach and arm me ! ' With slow steps from out An old storm-beaten, russet, many-stain'd Pavilion, forth a grizzled damsel came, And arm'd him in old arms, and brought a helm With but a drying evergreen for crest,

And gave a shield whereon the Star of Even

Half-tarnish'd and half-bright, his emblem, shone.

But when it glitter'd o'er the saddle-bow, They madly hurl'd together on the bridge; And Gareth overthrew him, lighted, drew, There met him drawn, and overthrew him again,

But up like fire he started: and as oft

As Gareth brought him grovelling on his knees, So many a time he vaulted up again ; Till Gareth panted hard, and his great heart, Foredooming all his trouble was in vain, Labour'd within him, for he seem'd as one That all in later, sadder age begins To war against ill uses of a life, But these from all his life arise, and cry, 'Thou heat made us lords, and can'st not put us down' I He half despairs; so Gareth seem'd to strike Vainly, the damsel clamouring all the while 'Well done, knave-knight, well-stricken, 0 good knight-knave--.

0 knave, as noble as any of all the knights— Shame me not, shame me not I have prophesied— Strike, thou art worthy of the Table Round—

His arms are old, he trusts the harden'd skin- Strike—strike—the wind will never change again.'

And Gareth hearing ever stronglier emote, And hew'd great pieces of his armour off him, But lash'd in vain against the harden'd skin, And could not wholly bring him under, more Than loud Southwesterns, rolling ridge on ridge,

The buoy that rides at sea, and dips and springs For ever; till at length Sir Gareth's brand Clash'd his, and brake it utterly to the hilt.

have thee now' but forth that other sprang, And all nnknightlike, writhed his wiry arms Around him, till he felt, despite his mail, Strangled, but straining ev'n his uttermost Cast, and so hurl'd him headlong o'er the bridge Down to the river, sink or swim, and cried, 'Lead, and I follow."

Nor can we keep back the grand passage in which the conflict with Night or Death takes place, and it appears that this is no conflict at all, except to the awe-struck imagination,—that to him who has faith, the struggle has been already fought out when the strength and craft of age-worn experience were conquered :—

"But when the Prince Three times had blown—after long hush—at last—

The huge pavilion slowly yielded up, " Thro' those black foldings, that which housed therein. High on a nightblack horse, in nightblack arms, With white breast-bone, and barren ribs of Death, And crown'd with fleshless laughter—some ten steps— In the half-light—thro' the dim dawn—advanced The monster, and then paused, and spake no word.

"Bat Gareth spake and all indignantly, Fool, for thou haat, men say, the strength of ten, Canst thou not trust the limbs thy God bath given, But must, to make the terror of thee more, Trick thyself out in ghastly imageries Of that which Life bath done with, and the clod, Leas dull than thou, will hide with mantling flowers As if for pity?' But he spake no word ; Which set the horror higher : a insides swoon'd ; The Lady Lyonors wrung her hands and wept, As doom'd to be the bride of Night and Death; Sir Gareth's head prickled beneath his helm ; And e'vn Sir Lancelot thro' his warm blood felt lee strike, and all that mark'd him were aghast.

"At once Sir Lancelot's charger fiercely neigh'd- At once the black horse bounded forward with him.* Then those that did not blink the terror, saw That Death was east to ground, and slowly rose.

But with one stroke Sir Gareth split the skull. Half fell to right and half to left and lay. Then with a stronger buffet he clove the helm As throughly as the skull ; and out from this Issued the bright face of a blooming boy Fresh as a flower new-born, and crying, 'Knight, Slay me not : my three brethren bad me do it, To make a horror all about the house, And stay the world from Lady Lyonors. They never dream'd the passes would be past.' Answer'd Sir Gareth graciously to one Not many a moon his younger, 'My fair child, What madness made thee challenge the chief knight Of Arthur's ball?' ' Fair Sir, they bad me do it. They hate the King, and Lancelot, the King's friend, They hoped to slay him somewhere on the stream, They never dream'd the passes could be past.'

"Then sprang the happier day from underground ; And Lady Lyonors and her house, with dance And revel and song, made merry over Death, As being after all their foolish fears And'horrors only proven a blooming boy.

So large mirth lived and Gareth won the quest."

The application of the inner meaning in the story of Gareth to the whole cycle of Arthurian idylls is, of course, apparent. The prepara- tion for Arthur's glorious reign, like Gareth's homely preparation for his great quest, is the simple privacy of the King's childhood and youth when no one knew that he should be king at all, and his life was the life of the fosterchild of Sir Anton's unknown wife. His first victories, as the founder of the true chivalry, against barbarian and earthly pride, were, like Gareth's against the Morning Star and the Noonday Sun, to be glorious and easy ; but as his reign went on, the struggle was to become more tenacious against the ever hardening and more vindictive resistance of the half-subjugated passions. In the evening of his reign the victory was to be hardly won, so won that the lookers-on half despaired of its being won at all ; but when the last awful and terror-striking battle against his enemies should have been fought, and the great King should pass away into the valley of Avilion, he would find that the final change was but one of seeming, and that he had virtually overcome death in the last great struggle, before he had passed through death at all. This is, we take it, something like the idea which makes the story of Gareth so fine an introduction to the rise and fall of the great realm of the great King whose reign, in spite of seeming defect, was to be for everlasting.

As to the poetic execution of the poem, we will only say that it has much of the Homeric sweetness and power of Mr. Tennyson's Ulysses,' and much also of the bird-like beauty of those sivallow flights of song' which are peculiar to Mr. Tennyson, and come upon our ear like the song of the lark when one turns inland after

* This is a slight verbal error; it would seem as it Sir Lancelot's charger bounded forward with Sir Lancelot, " him " referring only to Sir Lancelot. It is really Gareth who rides Sir Lancelot's charger.

listening to the sound of the breakers. What can be moire like the grave sonorous music of the ' Ulysses' than that grand comparison of Gareth's ill-success in beating down the Evening Star' to the picture of the "loud South westerns rolling ridge on ridge" against

"The buoy that rides at sea, and dips and springs For ever."

And what more lovely than Lynette's happy songs, as the knight whom she has treated so scornfully, but who has subdued her acorn by his valour and simplicity, his patience, and his valour, wins ever fresh successes before her eyes :—

"0 Sun, that wakenest all to bliss or pain, 0 moon, that layest all to sleep again,

Shine sweetly : twice my love bath smiled on me."

"0 dewy flowers that open to the sun, 0 dewy flowers that close when day is done,

Blow sweetly : twice my love bath smiled on me."

"0 birds, that warble to the morning sky, 0 birds that warble as the day goes by, Sing sweetly ; twice my love bath smiled on me."

Whether we take Gareth and Lynette simply as a separate tale of Arthurian chivalry, or as a prelude to the whole story of the chivalry which grows and falls through the cycle of Mr. Tennyson's slowly completed epic, we cannot think that it has been surpassed in beauty by any other. " Guinevere" and the "Passing of Arthur" will always stand the first of the cantos in pathos and tragic power. But for the dawning of the great dream, it would be hardly possible to imagine a finer vision than Gareth and

Lynette.'

Previous page

Previous page