BOOKS

An awkward friend

Colin Welch

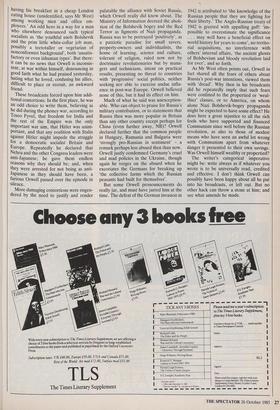

ORWELL: THE WAR COMMENTARIES edited by W.J.West

Duckworth and the BBC, f14.95

If recordings had been miraculously made of the Worcester County Lunatic Asylum Band in 1879, they would be greatly prized, not perhaps for their purely musical value but because the conductor was Elgar. We would listen spellbound, striving to catch through the hiss and cracklings, thumps and brays, fugitive pre- monitions of Enigma or The Kingdom. Even less alluring than the music-making of lunatics sounds a collection of weekly wartime news commentaries called Through Eastern Eyes, spoken mostly by Indians and put out by the Indian section of the BBC's Eastern Service between 1941 and 1943. Yesterday's news and mashed potatoes are notoriously stale; and news in wartime is more perishable still, with prop- aganda and censorship thriving at the expense of truth, the first casualty. But these commentaries were written by George Orwell — well, that does make a difference, though I fancy the Orwell buff will get more out of these pages than the student of the second world war.

He will learn a lot about his hero, much to his credit, some not particularly so. Whoever starts reading under any delusion that Orwell was infallibly percipient, sensi- ble and truthful will finish a wiser man, as Orwell himself was, to be fair. But the charitable reader who pays attention to Mr West's shrewd and witty footnotes will note how often, where Orwell strays from what we now know to have been true, the truth was not available to him or untruths had been fed to or forced on him, not least by the fantastically pro-Soviet Ministry of Information (or Truth?), which banned Animal Farm. If occasionally bored or irritated, the charitable reader must also wonder how he would have met the need to produce 1500 or so words a week, intelligible to an Indian audience, designed to persuade it that our cause was just and would prevail, with the pencil or shadow of the censor falling constantly on the paper. Hackwork, to be sure, but what a hack! And the odd mordant sarcasm reminds us who the hack was.

What the censor cut out is here restored, wherever legible. Orwell wrote that the extra-territorial treaties 'were imposed on the unwilling Chinese': the censor judi- ciously preferred 'were made with the Chinese'. The censor removed completely an account of the Labour party conference of 1942. Why? The Labour party was a very different animal in those days. It expressed complete confidence in Chur- chill and rejected `by an overwhelming vote' all political co-operation with the Communist party. I hope it was not the last fact which stuck in the censor's gullet.

The censor could on occasion appear more far-sighted than Orwell (and Stalin). Orwell reported Stalin's intent to destroy the German armies in 1942, and bade Indians remember that Stalin did not boast idly. The censor had this out, but was not always so discriminating. He permitted Orwell to describe Java as 'a tough nut (for the Japanese) to crack' and Singapore as 'a powerful fortress with very heavy guns', its capture not 'an easy business . . . impossi- ble without enormous losses, which the Japanese may not be ready to face.' Orwell declared Australia 'an enormous country which it would take several years to over- run completely, even if there were little or no resistance.' Did not the last clause raise a censorious eyebrow? Orwell planted fictitious Axis submarine bases, Japanese tourists and fifth columnists in Vichy Madagascar and a fictitious 'large unit of the RAF' in central China; he also referred to 'undoubted' though quite imaginary Axis schemes to invade America via Bra- zil. The censor indulgently let all this through. Orwell with a straight face lauded 'the firm behaviour of the Egyptian people . . united under its natural leader' (who was King Farouk!) and declared that there was 'no kind of Quisling activity whatever' in Russia. This boast was belied by Gener- al Vlassov and his troops (of whose exist- ence Orwell may not have been aware) and made plausible only by the Germans' insane rebuffs to all Russian offers of collaboration.

With common sense and hindsight we can smile at such stuff, as also at Orwell's donning the mantle of Liddell Hart and `I'm legless' pontificating about the strategic and tactic- al significance of distant `strongpoints', dustheaps and swamps which neither he nor anyone else had ever heard of before. An ironic comment on these far-fetched military speculations is supplied by Horra- bin's accompanying maps, on which the town (?) of Jarabub moves about a hun- dred miles southwards in a few months. But we must also feel sympathy for the clever man forced to speak of what he could not know, and gratitude that fate did not put us in his shoes. One factor which peculiarly fitted Orwell to speak for a Britain at war was his own dour and puritanical, if intermittent, passion for the austerity, scarcities and egalitarianism by which Britain chose or was forced to wage war. Earlier in Barcelo- na he had noted with approval the wealthy classes apparently wiped out, the bourgeois killed or in flight, almost no 'well-dressed' people, only rough working-class clothes, blue overalls, various military uniforms. In all this he had recognised immediately 'a state of affairs worth fighting for', as if it were an end in itself rather than a means W victory. As Britain too became more drab, regimented and levelled down, so she too became more worth fighting for. With a dour relish Orwell welcomes soap ration- ing, supports the demands of 'ordinary people' for 'greater sacrifices' and for stiffer penalties for black marketeers and `the selfish minority' who behaved as if there were no war and who must 'be dealt with once and for all'. I wonder if the censor, who cut them out, discerned in these sentiments, as Mr West does, per- verse adumbrations of Nineteen EightY- Four.

Orwell hailed the 1942 Budget as 'demo- cratic', hastening equality and the end of class distinctions. He also welcomed the prohibition of 'what is known as luxurY feeding' which, together with conscription and the rationing of clothes and petrol, was making Britain 'more truly a democracy'. A weird definition of democracy is here implied: had Hitler bled and starved the Germans more than he did, would Ger- many too have become 'more truly a democracy'? A like weirdness appears 111- the very next broadcast, which attributes Soviet Russia's 'inevitable' entry into the war on the side of the democracies to the fact that her 'national philosophy is a democratic one'. This surely is to do Hitler an injustice. As the exam papers say, `discuss'.

During this period Orwell's hero was Sir Stafford Cripps: outstanding simplicity, austerity, gives away his earnings at the Bar, vegetarian, teetotaller, devout prac- tising Christian, `to be seen every morning having his breakfast in a cheap London eating house (unidentified, says Mr West) among working men and office em- ployees.' An odd hero in a way for a man who elsewhere denounced such typical socialists as 'the youthful snob Bolshevik and the prim little white-collar job man, possibly a teetotaller or vegetarian of nonconformist background', both 'unsatis- factory or even inhuman types'. But there: it can be no news that Orwell is inconsis- tent, at war within himself, denouncing in good faith what he had praised yesterday, hating what he loved, confusing his allies, difficult to place or recruit, an awkward friend.

These broadcasts forced upon him addi- tional contortions. In the first place, he was an odd choice to write them, believing as he did during the phoney war, according to Tosco Fyvel, that freedom for India and the rest of the Empire was the only important war aim, that Hitler was unim- portant, and that any coalition with Stalin against Hitler might impede the struggle for a democratic socialist Britain and Europe. Repeatedly he declared that Nehru and the other Congress leaders were anti-Japanese; he gave them endless reasons why they should be; and, when they were arrested for not being as anti- Japanese as they should have been, a furious Orwell passed over the episode in silence.

More damaging contortions were engen- dered by the need to justify and render palatable the alliance with Soviet Russia, which Orwell really did know about. The Ministry of Information decreed the aboli- tion of the Bolshevik bogey and the Red Terror as figments of Nazi propaganda. Russia was to be portrayed 'positively', as a patriotic paradise for small savers, property-owners and individualists, the home of learning, science and culture, tolerant of religion, ruled now not by doctrinaire revolutionaries but by mana- gers and technicians, intent on practical results, presenting no threat to countries with 'progressive' social politics, neither seeking nor able to exercise undue influ- ence in post-war Europe. Orwell believed none of this, but it had its effect on him.

Much of what he said was unexception- able. Who can object to praise for Russia's military contribution, or to statements that Russia then was more popular in Britain than any other country except perhaps for China (even further away, NB)? Orwell declared further that the common people in Hungary, Rumania and Bulgaria were `strongly pro-Russian in sentiment' — a remark perhaps less absurd then than now. Orwell justly condemned Germany's cruel and mad policies in the Ukraine, though again he verges on the absurd when he excoriates the Germans for breaking up `the collective farms which the Russian peasants had built for themselves'.

But some Orwell pronouncements do really jar, and must have jarred him at the time. The defeat of the German invasion in 1942 is attributed to 'the knowledge of the Russian people that they are fighting for their liberty.' The Anglo-Russian treaty of 1942 is greeted with appalling guff: 'im- possible to overestimate the significance . . . may well have a beneficial effect on world history for years to come', no territo- rial acquisitions, no interference with others' internal affairs, 'the ancient ghosts of Bolshevism and bloody revolution laid for ever', and so forth.

As Mr West often points out, Orwell in fact shared all the fears of others about Russia's post-war intentions, viewed them with 'dread'. Why then in his broadcasts did he repeatedly imply that such fears were confined to the propertied or 'weal- thier' classes, or to America, on whom alone Nazi Bolshevik-bogey propaganda might be expected to have some effect? He does here a great injustice to all the rich fools who have supported and financed Communism since well before the Russian revolution, as also to those of modest means who have seen an awful lot wrong with Communism apart from whatever danger it presented to their own savings. Was Orwell himself wealthy or propertied?

The writer's categorical imperative might be: write always as if whatever you wrote is to be universally read, credited and effective. I don't think Orwell can possibly have been happy about all he put into his broadcasts, or left out. But no other hack can throw a stone at him; and see what amends he made.

Previous page

Previous page