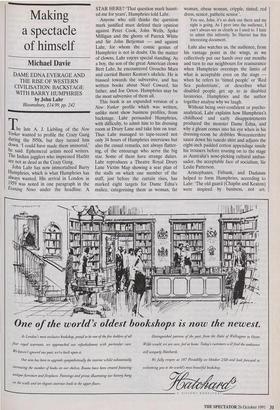

Making a spectacle of himself

Michael Davie

DAME EDNA EVERAGE AND THE RISE OF WESTERN CIVILISATION: BACKSTAGE WITH BARRY HUMPHRIES by John Lahr Bloomsbury, £14.99, pp. 242 The late A. J. Liebling of the New Yorker wanted to profile the Crazy Gang during the 1950s, but they turned him down. 'I could have made them immortal,' he said. Ephemeral artists need writers. The Indian jugglers who impressed Hazlitt are not as dead as the Crazy Gang. John Lahr has now immortalised Bally Humphries, which is what Humphries has always wanted. His arrival in London in 1959 was noted in one paragraph in the Evening News under the headline: A

STAR HERE? 'That question mark haunt- ed me for years', Humphries told Lahr.

Anyone who still thinks the question mark justified must defend their opinion against Peter Cook, John Wells, Spike Milligan and the ghosts of Patrick White and Sir John Betjeman — and against Lahr, for whom the comic genius of Humphries is not in doubt. On the matter of clowns, Lahr enjoys special standing. As a boy, the son of the great American clown Bert Lahr, he encountered Groucho Marx and carried Buster Keaton's ukelele. He is biassed towards the subversive, and has written books about Noel Coward, his father, and Joe Orton. Humphries may be the most subversive of them all.

This book is an expanded version of a New Yorker profile which was written, unlike most show business profiles,- from backstage. Lahr persuaded Humphries, with difficulty, to admit him to his dressing room at Drury Lane and take him on tour. Thus Lahr managed to tape-record not only 34 hours of Humphries interviews but also the casual remarks, not always flatter- ing, of the entourage who serve the big star. Some of them have strange duties. Lahr reproduces a Theatre Royal Drury Lane Victim Map showing a seat plan of the stalls on which one member of the staff, just before the curtain rises, has marked eight targets for Dame Edna's malice, categorising them as woman, fat

woman, obese woman, cripple, tinted, red dress, senior, pathetic senior'.

You see, John, it's so dark out there and my sight is going, As I peer into the audience, I can't always see as clearly as I used to. I hate to admit this infirmity. So Harriet has this interesting document.

Lahr also watches us, the audience, from his vantage point in the wings, as we collectively put our hands over our mouths and turn to our neighbours for reassurance when Humphries oversteps the limits of what is acceptable even on the stage when he refers to 'tinted people' or 'Red Sea pedestrians', or describes what disabled people get up to in disabled lavatories. Humphries and the author together analyse why we laugh.

Without being over-confident or psycho- analytical, Lahr explains how Humphries's childhood and early disappointments produced the monster Dame Edna, and why a gleam comes into his eye when in his dressing-room he dribbles Worcestershire sauce down his tuxedo shirt and adjusts the eight-inch padded cotton appendage inside his trousers before roaring on to the stage as Australia's nose-picking cultural ambas- sador, the acceptable face of socialism, Sir Leslie Patterson.

Aristophanes, Firbank, and Dadaism helped to form Humphries, according to Lahr: The old guard (Chaplin and Keaton) were inspired by business, not art. Humphries was inspired by art, not busi- ness.' Humphries, apparently, leads the life of a comedian because making a spec- tacle of himself is the only way he can make life interesting, which necessarily (for him) involves disconcerting and con- trolling others. The 'actual' Barry Humphries — an elusive figure — does not like being laughed at himself, says one of his entourage.

Occasional deep thoughts about the seriousness of comedy notwithstanding, Lahr's exhilarating and highly intelligent book is full of laughs, not too long — a tape-recorder for once is kept in its place — and wrapped in an appropriately dazzling jacket by the American artist Paul Davis.

Previous page

Previous page