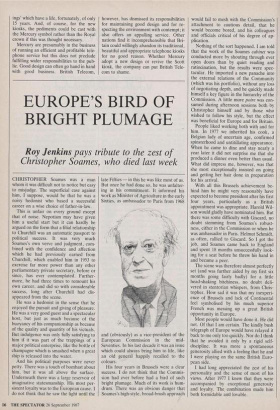

EUROPE'S BIRD OF BRIGHT PLUMAGE

Roy Jenkins pays tribute to the zest of

Christopher Soames, who died last week

CHRISTOPHER Soames was a man whom it was difficult not to notice but easy to misjudge. The superficial case against him, I suppose, would be that he was a noisy hedonist who based a successful career on a wise choice of father-in-law.

This is unfair on every ground except that of noise. Nepotism may have given him a useful start but it can hardly be argued on the form that a filial relationship to Churchill was an automatic passport to political success. It was very much Soames's own verve and judgment, com- bined with the confidence and affection which he had previously earned from Churchill, which enabled him in 1953 to exercise far more power than any other parliamentary private secretary, before or since, has ever contemplated. Further- more, he had three times to remount his own career, and did so with considerable success, long after Churchill had dis- appeared from the scene.

He was a hedonist in the sense that he enjoyed the pursuit and giving of pleasure. He was a very good guest and a spectacular host, but just as much because of the buoyancy of his companionship as because of the quality and quantity of his victuals. But indulgence was only fully satisfying to him if it was part of the trappings of a major political enterprise, like the bottle of champagne which is smashed when a great ship is released into the water.

And his political purposes were never petty. There was a touch of bombast about him, but it was all above the surface. Underneath there was a large reservoir of imaginative statesmanship. His most per- sistent loyalty was to the European cause. I do not think that he saw the light until the late Fifties — in this he was like most of us. But once he had done so, he was unfalter- ing in his commitment. It informed his work as Minister of Agriculture in the early Sixties, as ambassador to Paris from 1968 and (obviously) as a vice-president of the European Commission in the mid- Seventies. In his last decade it was an issue which could always bring him to life, like an old general happily recalled to the colours.

His four years in Brussels were a clear success. I do not think that the Commis- sion had ever before had a bird of such bright plumage. Much of its work is hum- drum. There was an obvious danger that Soames's high-style, broad-brush approach would fail to mesh with the Commission's attachment to cautious detail, that he would become bored, and his colleagues and officials critical of his degree of ap- plication.

Nothing of the sort happened. I am told that the work of the Soames cabinet was conducted more by shouting through ever open doors than by quiet reading and ratiocination, but the results were spec- tacular. He imported a new panache into the external relations of the Community (which was his portfolio), without any loss of negotiating depth, and he quickly made himself a key figure in the hierarchy of the Commission. A little more poire was con- sumed during afternoon sessions both by Christopher himself and by those who wished to follow his style, but the effect was beneficial for Europe and for Britain.

People liked working both with and for him. In 1977 we inherited his cook, a Belgian lady of uncertain age, confirmed spinsterhood and untitillating appearance. When he came to dine and stay nearly a year later it did not surprise me that she produced a dinner even better than usual. What did impress me, however, was that she most exceptionally insisted on going and getting her hair done in preparation for his arrival.

With all this Brussels achievement be- hind him he might very reasonably have expected to become president after his first four years, particularly as a British appointment was appropriate. Harold Wil- son would gladly have nominated him. But there was some difficulty with Giscard, no doubt stemming from Soames's robust- ness, either in the Commission or when he was ambassador in Paris. Helmut Schmidt, as often, rallied to Giscard. So I got the job, and Soames came back to England and spent 18 months unsuccessfully look- ing for a seat before he threw his hand in and became a peer.

The scene was therefore almost perfectly set (and was further aided by my first six months going fairly badly) for a little head-shaking bitchiness, no doubt deli- vered in stentorian whispers, from Chris- topher. How sad it was that my inexperi- ence of Brussels and lack of Continental feel symbolised by his much superior French was messing up a great British opportunity in Europe.

Most people would have done it. He did not. Of that I am certain. The kindly bush telegraph of Europe would have relayed it back to me only too quickly. Nor do I think that he avoided it only by a rigid self- discipline. It was more a spontaneous generosity allied with a feeling that he and I were playing on the same British Euro- pean side.

I had long appreciated the zest of his personality and the sense of most of his views. After 1977 I knew that they were accompanied by exceptional generosity and loyalty. The, combination made him both formidable an'd lovable.

Previous page

Previous page