LORD BROUGHAM AM) THE PRESS IN MALTA.

Ix the House of Lords on Tuesday last, Lord BaouGnam stigma- tized in very severe language the Ordinance respecting the Press recently issued in the island of Malta, on the recommendation of the Commissioners for inquiring into the atiltirs of that island. He has given notice of a specific motion on the subject for next week.

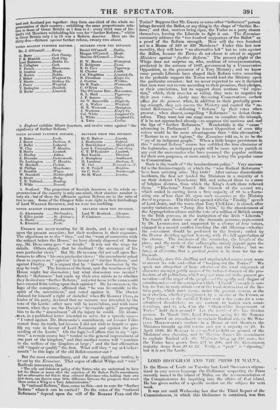

It was not until Wednesday last that the Third Report of the Commissioners, in which this Ordinance is contained, was first printed by the House of Commons and delivered to Members of Parliament ; so that the criticisms of Lord BROUGHAM were di- rected against a document of which, at the time when he spoke, the public could have no knowledge. Looking at the tone and tenor of Lord BROUGHAM'S remarks, it would be imagined that the Maltese Ordinance was a new restric- tion, nearly tantamount in point of severity to a censorship, upon a country where freedom of the press had hitherto prevailed. But the facts of the case are directly the reverse. Down to the mo- tnent when this Ordinance was issued, there existed in Malta a censorship of the closest kind—practically, perhaps, the closest censorship in Europe. The feelings under the influence of which this restrictive system has been maintained, may be judged of by the language of the Duke of WELLINGTON when this subject was debated last year in the House of Lords—" that it was not less pre- posterous to establish freedom of the press in Malta, than it would be to establish freedom of the press on the quarter-deck of a man of war." This habit of considering Malta as a mere garrison, to- gether with the fear of offending Italian potentates by publications issuing from that island and directed against their Governments, has caused the maintenance of a censorship so rigid that the press has been all but mute and dead.

Such was the state of the press when the Commissioners of In- quiry were sent to Malta. They had to investigate the whole government of the island; judicial as well as administrative ; and they recommended many separate reforms in all the departments of state, several of which the Colonial Office have adopted at their suggestion. We may take a future opportunity of giving some account of these recommendations ; which are embodied in the three Reports laid before Parliament, and which appear to us to be conceived in a spirit of liberality and beneficence towards the inha- bitants of the island.

In abolishing the censorship, the Commissioners were of course called upon to provide securities against abuses of the press,—a subject entirely new to the law of Malta. It is notorious that there is no problem in legislation more difficult of solution than this, or morefruitful in controversy as to provisions of detail ; and the inherent perplexities of the problem are much aggravated by the peculiar position of the Maltese community. If, then, on lookingto the Ordinance recently published, we perceive that it really does guarantee to the Maltese the main and essential bene- fits of a free press, we are not all disposed to go along with the unmeasured language of Lord BROUGHAM in denouncing particu- lar enactments which may appear to us open to debate or objec- tion.

The main benefit, unquestionably, which the people of' Malta both wish to derive and ought to derive from the abolition of the censorship, is, the liberty of freely canvassing and censuring the government and administration of their own island, and the govern- ment and administaation of England in so far as it affects their in- terests. Does the Ordinance secure to them this liberty of unre- served political discussion ? We think it does. As far as we are able to construe its provisions in reference to political libel„ accom- panied as they are with elaborate explanations from the Commis- sioners, we think it is decidedly less restrictive of public discus- sion than the law of political libel as it has been laid down by the Judges in England. If the criminal law of libel, as it has been au- thoritatively laid down in England, had been at once made appli- cable to Malta, the liberty of censuring acts of public administra- tion would have been less complete and less effectually protected than it is under the recent Ordinance. The terms used by the Commissioners, in defining prohibited publications, are much more precise and much more limited than those which are recognized in the English criminal law. We have not room here to transcribe the third chapter of the Ordinance, but we shall be surprised if Lord BROUGHAM is able to show the contrary of that which we here as- sert. And we cannot but think, that if the same latitside of polis tical discussion as the English law permits in England, be insured in Malta, the people of that island will have been placed in posses- sion of the substantial and principal benefits which a free press can confer upon them. It would scarcely be reasonable to expect that the law should sanction greater freedom of discussion in the de- pendent colony of Malta, than it sanctions among the people of England itself.

The observations of Lord IThotrentAm, on Tuesday, were directed principally against that part of the Ordinance which prohibits pub- lications censuring or reviling any person in a private capacity, and publications reviling, ridiculing, or otherwise insulting any essen- tial or fundamental doctrine of the Christian religion.

With regard to publications in disparagement of private charac- ter, the prohibition of the Commissioners is very strict and sweep- ing; and their views on this subject, which are explained at length in the Notes on the Ordinance, will undoubtedly raise a great deal of debate. We shall only remark here, that in order to understand the real extent pf their prohibition, it is absolutely necessary to read the restrictive explanations which they affix to the words "private capacity." With regard to publications on the subject of the Christian re- ligion, the Ordinance forbids ridicule or insult, as distinguished from serious and argumentative challenge. This is, in point of fact, the distinction which has been often laid down by the Eng- lish Judges : and we are quite sensible that the difficulty of draw- ing the line between that which is reasoning and that which is ridicule, in any particular book, has led to abusive and unjust de- cisions in the English Courts. But we much doubt whether this

prohibition will not be among the most acceptable parts of the Ordinanoe to the people of Malta, intensely attached as they are to the Catholic religion, and feeling as they do that their creed is regarded with no great favour or indulgence by the great body of the English public. We were confirmed in this opinion by a letter which appeared in the Morning Chronicle of Friday last, written by 'Mr. MITROVITCH, a Maltese agent sent to England to represent the grievances of his countrymen, and an earnest advocate for the emancipation of the press in the island. This letter, written in consequence of Lord %osmium's observations, particularly en- treats that whatever other alterations may be made in the Ordi- nance, the clause prohibiting ridicule or insult to the Catholic re- ligion may be retained, " as essential in a: place where the persua- sion of the inhabitants differs from that of the governing power." The letter of Mr. MITROVITCH is a remarkable evidence of the sensitive dispositions of the Maltese on the subject of their religion.

These few remarks are far from having exhausted all that we could say of this Ordinance, both in point of substance and in point of form. But we have no room for further animadversion at present ; and we shall only repeat, that it is a document the bearing of which cannot be fairly or fully appreciated except when studied in conjunction with the explanations annexed by the Com- missioners.

Previous page

Previous page