Drabble's Companion

Auberon Waugh

The Oxford Companion to English Literature Fifth edition edited by Margaret Drabble (OUP £15)

it Paul Harvey, introducing the first

■ ...3 edition of his brilliant and irreplaceable Oxford Companion to English Literature in 1932, stated that its purpose was to be 'a useful companion to the ordinary, every- day reader of English literature'. Miss Drabble claims the same purpose, which is distinctly heartening, while admitting that her revision 'inevitably reflects the increas- ing specialisation and professionalism of English studies'.

I see no obvious, let alone inevitable, reason why it should do any such thing. The ordinary, everyday reader does not concern himself with English studies, however specialist and professional they may have become. More often than not, he will apply to the Companion to jog his memory about something he has already read, to pinpoint a date or a spelling, or to help solve a clue in the Times crossword puzzle; just occasionally to explain a refer- ence — usually classical — in something he is reading. There is all the difference in the world between English literature as it is enjoyed by the ordinary, everyday reader, and English Literature (usually abbrevi- ated into Eng. Lit) which is something studied in the universities as an academic

discipline, often by women.

Sir Paul admits two main elements into the general scheme of his work. The first is `a list of English authors, literary works and (more mysteriously) literary societies which have historical or present import- ance'. The second is 'the explanation of allusions commonly met with, or likely to be met with, in English literature, insofar as they are not covered by the articles on English authors and their works'. In this list, in addition to the characters of English fiction and mythology, one found the names of characters of classical mythology, 'with saints, heroes, statesmen, philo- sophers,, men of science, artists, musicians, actors . . . literary forgers and imposters in short . . . every kind of celebrity'.

When Miss Drabble arrived on the scene, she found that in her anxiety to add to existing entries — providing references to such sources as the Early English Text Society which are unlikely to be found at the elbow of most ordinary, everyday readers, as well as chronicling the moderns — she had to make drastic cuts: 'Ruthlessly. I resolved to drop most of Harvey's allu- sions commonly met with, or likely to be met, in English literature,' she writes. While retaining most of the entries on English and Irish mythology, 'I have not even attempted to cover classical allusions — not because I assume everyone is familiar with them, but rather because they are so

numerous they can only be properly co- vered in a dictionary of classical mythology.'

This seemed to me, on reading Miss Drabble's preface, to be a serious error of judgment. No doubt it is a product of her concern for 'increasing specialisation and professionalism', but there is all the differ- ence in the world between classical mythol- ogy as it is studied by experts on the subject and classical mythology as it appears dotted around most English litera- ture until the second half of the 20th century. Only a tiny proportion of classical mythology is memorable, in the sense of 1066 and All That, and only a tiny propor- tion has ever caught the English literary imagination. Miss Drabble refuses to tell us even about Diogenes the Cynic, let alone about Leda and the Swan. Nobody wishes to apply to specialist information on this subject. It was one of the glories of Sir Paul Harvey's book that he seemed to know exactly what one would want to look up.

But the classics do not change much, and so long as one sees Miss Drabble's Com- panion as a supplement to Sir Paul Har- vey's, rather than as a replacement for it, one is happy to report that she seems to have done her job very well indeed. She has avoided most of the traps, and kept faithfully to Sir Paul's original conception when he wrote, in 1932; 'Original literary appreciation is not attempted, and com- ments verging on aesthetic criticism are intended to give rather a conventional view.'

This seems to me essential to any refer- ence book. Against the temptation to academic esotericism nowadays runs a journalistic tendency to classify everything by snap decisions — somebody is 'in', somebody else 'out' — or by some imagin- ary pecking order. The worst offender in this field is Martin Seymour-Smith, whose Guide to Modern World Literature (Wolfe 1972) will remain a monument to the egotistical school of criticism. I could find very little evidence indeed either of special pleading or of personal animus. It is curious that in a list of 20th-century Times editors she should exclude the name of Harold Evans, but no more than curious. It would be a fair criticism that she gives more attention to modern literature than it deserves — I was shocked to discover that of the 16 winners of the Booker prize, only seven have no separate entry — but this criticism applies only if one sees the book as a substitute for Harvey's volume, rather than as a supplement to it.

One could complain that where Harvey (in my 1960 impression of the Third Edi- tion) summarises the literary achievement of D.H.Lawrence in 13 lines, Miss Drabble takes 146 lines in 1985. But this may reflect no more than the verbosity of the age in which we live. T..E.Lawrence takes 18 lines in 1960, 82 in 1985. One could reasonably complain of entries like 'Dissociation of Sensibility' — a phrase coined by T.S.Eliot in an essay entitled 'The Metaphysical Poets' — but I am afraid this may be part of the price we have to pay for having the book at all. The Eng. Lit. industry is a much bigger market than that represented by Times crossword addicts, or even by ordinary, everyday readers of English liter- ature.

The dustjacket promises great excite- ments, claiming that Miss Drabble has 'widened the Companion's appeal by admitting to the canon topics once thought to be beyond the pale of literary respecta- bility (comic strips, detective stories, scien- ce fiction, children's literature)'. None of these is in much evidence. Although Raymond Chandler is there, I found no comic strips in a day's browsing: not Beano nor Dandy nor even Private Eye (which surely merits space, after a quarter of a century, more than Stephen Spender, after 76 years). There is no mention of Super- man, nor Mickey Mouse, nor Donald Duck (described by Horace Winship as a greater actor than Greta Garbo) although all these characters are very much alive in the literary consciousness of our day, if not yet on any Eng. Lit. syllabus.

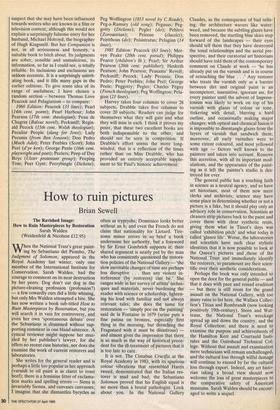

On the 'in' and 'out' basis, one might observe that Miss Drabble modestly ex- cludes any mention of her own contribu- tion to the English novel, while myster- iously including the slightly younger novel- ist, Melvyn Bragg, who, she says, is 'best known as a presenter of arts programmes on television'. There is a temptation to suspect that she may have been influenced towards writers who are known in a film or television context, although this would not explain a surprisingly fulsome entry for her husband, Michael Holroyd, the biographer of Hugh Kingsmill. But her Companion is not, in all seriousness and honesty, a suitable book to bitch about. Its judgments are sober, sensible and unmalicious, its information, so far as I could see, is totally reliable. Its inclusions and exclusions are seldom eccentric. It is a surprisingly unirrit- ating book, and it fills many gaps in the earlier editions. To give some idea of its range of usefulness, I have chosen a random section – between Thomas Love Peacock and Pelagianism – to compare: 1960 Edition: Peacock (33 lines); Pearl (14th cent. poem); Pearl Harbour; John Pearson (17th cent. theologian); Peau de Chagrin (Balzac novel); Pecksniff; Regin- ald Pecock (15th cent. Welsh theologian); Peculiar People (slang for Jews); Lady Pecunia (from Ben Jonson); Don Pedro (Much Ado); Peter Peebles (Scott); John Peel (d'ye ken); George Peele (16th cent. playwright and poet); Peelers; Peep of Day Boys (Ulster protestant group); Peeping Tom; Peer Gynt; Peerybingle (Dickens); Peg Woffington (1853 novel by C.Reade); Peg-a-Ramsey (old song); Pegasus; Peg- gotty (Dickens); Pegler (do); Pehlevi (Zoroastrian); Peirene (classics); Peirithous (do); Peisistratus; Pelagian (14 lines).

1985 Edition: Peacock (63 lines); Mer- vyn Peake (20th cent. pseud); Philippa Pearce (children's lit.); Pearl; Sir Arthur Pearson (20th cent. publisher); Hesketh Pearson; John Pearson; Peasants' Revolt; Pecksniff; Pecock; Lady Pecunia; Don Pedro; Peter Peebles; John Peel; George Peele; Peggotty; Pegler; Charles Peguy (French theologian); Peg Woffington; Pela- gian (21' lines).

Harvey takes four columns to cover 28 subjects, Drabble takes five columns to cover 20 subjects. Readers can judge for themselves what they will gain and what they will miss in each. I think it proves my point, that these two excellent books are both indispensable to the other, and should not be seen in competition. If Drabble's effort seems the more long- winded, that is a reflection of the times rather than on Miss Drabble, who has provided an entirely acceptable supple- ment to Sir Paul's historic achievement.

Previous page

Previous page