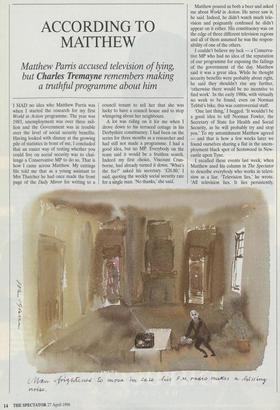

ACCORDING TO MATTHEW

I HAD no idea who Matthew Parris was when I started the research for my first World in Action programme. The year was 1983, unemployment was over three mil- lion and the Government was in trouble over the level of social security benefits. Having looked with dismay at the growing pile of statistics in front of me, I concluded that an easier way of testing whether you could live on social security was to chal- lenge a Conservative MP to do so. That is how I came across Matthew. My cuttings file told me that as a young assistant to Mrs Thatcher he had once made the front page of the Daily Mirror for writing to a council tenant to tell her that she was lucky to have a council house and to stop whingeing about her neighbours.

A lot was riding on it for me when I drove down to his terraced cottage in his Derbyshire constituency. I had been on the series for three months as a researcher and had still not made a programme. I had a good idea, but no MP. Everybody on the team said it would be a fruitless search. Indeed my first choice, Viscount Cran- borne, had already turned it down. 'What's the fee?' asked his secretary. T26.80,' I said, quoting the weekly social security rate for a single man. 'No thanks,' she said. Matthew poured us both a beer and asked me about World in Action. He never saw it, he said. Indeed, he didn't watch much tele- vision and poignantly confessed he didn't appear on it either. His constituency was on the edge of three different television regions and all of them assumed he was the respon- sibility of one of the others.

I couldn't believe my luck — a Conserva- tive MP who had no idea of the reputation of our programme for exposing the failings of the government of the day. Matthew said it was a great idea. While he thought security benefits were probably about right, he said they shouldn't rise any further, `otherwise there would be no incentive to find work'. In the early 1980s, with virtually no work to be found, even on Norman Tebbit's bike, this was controversial stuff.

`One last thing,' I begged. 'It wouldn't be a good idea to tell Norman Fowler, the Secretary of State for Health and Social Security, as he will probably try and stop you.' To my astonishment Matthew agreed — and that is how a few weeks later we found ourselves sharing a flat in the unem- ployment black spot of Scotswood in New- castle upon Tyne.

I recalled these events last week, when Matthew used his column in The Spectator to describe everybody who works in televi- sion as a liar. 'Television lies,' he wrote. `All television lies. It lies persistently, instinctively and by habit.' From someone who makes a living writing for Rupert Murdoch, it appears that Matthew has lost none of his penchant for the controversial.

Newspaper journalists have it easy when it comes to lying. They are controlled, of course, but by a loose, self-regulated Press Complaints Commission. Television, in contrast, is hugely regulated. We face not only the Broadcasting Standards Council on taste and decency, the Broadcasting Complaints Commission on fairness and privacy, but also the Independent Televi- sion Commission, which has the ability to fine companies or even revoke their licences for a breach of its guidelines. At Granada we are only too aware of this, having paid half a million pounds for an infringement on a daytime magazine show.

So Matthew says television lies. I won- dered if our programme had lied. The first thing he did when arriving at the flat in Newcastle was to do a budget for the week. As a Conservative MP, his intention was to prove that social security payments were adequate. He told me, with all the prudence of a Chancellor on Budget day, that out of his £26.80 he would save £3. A bold boast, we thought, as we sat back and observed his life on the dole. True, I had been to the area before and had identified individuals and groups he should meet. True, we arranged with the local post office to get a shot of him receiving a notional £26.80, even though as a Tory MP he was not entitled to it. True, the whole exercise was contrived: a week's unemploy- ment can never be the same as a year's unemployment.

But had we lied? Here was a man who desperately wanted to prove that it was possible to live on social security pay- ments. We could not have forced him to do anything he didn't want to do. And the truth was that after only five days he ran out of money. Instead of saving £3 a week, he had nothing left to eat and nothing left to put in the electricity meter.

People might argue that this is what we had always intended — public humiliation of a Tory MP. 'It was rigged', to use Matthew's phrase. But how could it have Soon! Coming to a cinema near you! `Kids' the movie! been? If he had survived triumphantly, we would still have had to show the film imagine the fuss if we hadn't.

We called the programme For the Bene- fit of Mr Parris. To our astonishment, it attracted an audience of nearly 13 million viewers. That week World in Action was rated number eight on the 'Television Top Ten' list, a slightly giddy experience for us at the time. One television reviewer wrote that Matthew 'was the sort of Tory MP who used the softest voice to say the harshest things', probably an unfair description.

In the same way that writers choose words and phrases to describe their per- spective of events, television producers have to choose pictures and interviews to illustrate their reports. Editing is a neces- sary part of most media. Of course many current affairs programmes are advancing a thesis; that is their job. But do they lie? Not if all the official regulatory bodies and the courts have anything to do with it.

Matthew made much of the technology of television — the autocue, the earpiece and the reverse questions. During the 1980s, there was a fashion for showing off the paraphernalia of television: cameras were in shot, we saw sound booms swoop- ing across the screen and could even read the autocue. But the audience quickly grew tired of such gimmicks. Television is about the simple art of communication, and the fewer things that get between the communicator and the audience the better. Those things aren't lies; they just promote effective communication.

Television has the potential to be a force for good in the world. It can help correct injustice, expose corruption and influence the way that powerful people rule our lives. It has become an essential element of our democracy. Yes, it can also be crass and superficial, but no more so than the worst tabloid newspapers — some of which are owned by Matthew's current employer.

However, looking back, I have to admit that there was one fib in our film in New- castle. When Matthew ran out of money he was keen to get back to London. Under- standably, he did not relish a hungry two days in a cold flat. We agreed; the experi- ment was effectively over, the programme was complete. We had a couple of beers and said goodbye.

It is said that the experience changed his life, but he has never admitted that to me. Who knows, without us, today he might have been explaining to the Commons why BSE beef is safe. Instead, he resigned as an MP for a brilliant new career in journalism. I think we all agree he made the right deci- sion, even if he does sometimes get things wrong.

Charles Tremayne is head of factual pro- grammes at Granada Television.

Previous page

Previous page