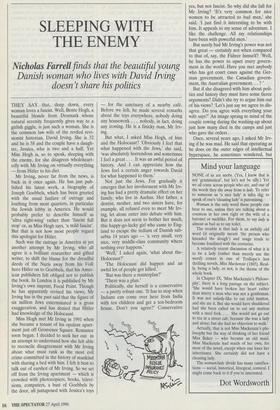

Mind your language

NONE of us are snobs. (Yes, I know that is not 'grammatical', but let's not be silly.) Yet we all come across people who are, and one of the words they shy away from is lady. To refer to someone as 'a nice lady' is infra dig; to speak of one's 'cleaning lady' is patronising.

Woman is the only word these people can bear to use, unless they are talking about a countess in her own right or the wife of a baronet or suchlike. For them, to say lady is almost as bad as to say toilet.

The trouble is that lady is an awfully old word (it originally meant 'the person who kneaded the dough') and usage tends to become fossilised with the centuries.

A relatively recent discussion of what it is to be a lady (rather than merely use the word) comes in one of Trollope's less thrilling novels, Miss Mackenzie (1865). Real- ly, being a lady, or not, is the theme of the whole book.

In Chapter IX, 'Miss Mackenzie's Philoso- phy', there is a long passage on the subject. 'She would have broken her heart rather than marry a man who was not a gentleman. It was not unlady-like to eat cold mutton, and she ate it. But she would have shuddered had she been called on to eat any mutton with a steel fork. . . . She would not go out to tea in a street cab, because she was a lady and alone; but she had no objection to walk.'

Actually, that is not Miss Mackenzie's phi- losophy but the way of thinking of her friend Miss Baker — who became an old maid. Miss Mackenzie had maids of her own, for most of the novel, except when one loses her inheritance. She certainly did not have a cleaning lady.

The woman/lady divide has many ramifica- tions — social, historical, liturgical, comical. I might come back to it if you're interested.

Dot Wordsworth

Previous page

Previous page