ARTS

From coast to coast

Elisabeth Anderson

The writer was sponsored by the United States American diary Information Agency, under the auspices of the International Visitors Program, to experi- ence aspects of American cultural life.

TWashington DC here's a grand old tussle going on here between culture and commerce. A rich benefactor offered to buy for Washing- ton Opera a derelict building which was coming up for sale at auction and could be converted into an opera house (at present the company lodges at the Kennedy Cen- ter). The building, though, had to be the defunct department store, Woodward & Lothrop: `Woodies' or nothing, the donor specified. City officials then decreed that at least half the space had to be used for shops — which, in effect, it was thought, would deter the opera company from bid- ding. But it did bid and did win and now insists that it needs the entire space. In the other corner, the city planners insist they need the money from the shops' taxes to rejuvenate decaying downtown Washington (an opera house would be tax-exempt). With remarkable understatement, the Washington Post summed up the situation: `Negotiations are sure to be complicated.'

Had a morning at the Kennedy Center (where I was allowed to peek into the Pres- ident's box in one of the auditoriums), returning in the evening for a concert by Andras Schiff playing Schumann. One unexpected bonus for concert-goers (or indeed for theatre- and opera-goers throughout America) is that programmes are always included in the price of the ticket.

Spent an afternoon in the studios of WETA, the public service broadcasting company. Sat in on the taping of Around Town, the Washington equivalent of BBC 2's Late Review. WETA's founder, Eliza- beth Campbell, an indomitable 93-year-old, still comes into the office every day, though, she told me, when the weather gets too bad she doesn't drive herself but lets a colleague give her a lift. Did the gallery and museum rounds: National Gallery, Corcoran, Hirshhorn, Renwick, Phillips Collection, Anacostia Neighborhood Museum, National Museum of Women in the Arts (which wasn't, I dis- cover, stridently feminist at all) .. .

0 Chicago my one item of news from Britain seems to be of interest here: mad cow dis- ease. Makes the newspapers' front page (most days) and the feature pages (often): Ray Moseley in the Chicago Tribune about Simpsons in the Strand: 'The two waiters who serve lamb are being worked to exhaustion. The poor beef carver could take naps between servings. Somehow, in the chatter around the room, the word "beef" never seems to be mentioned.'

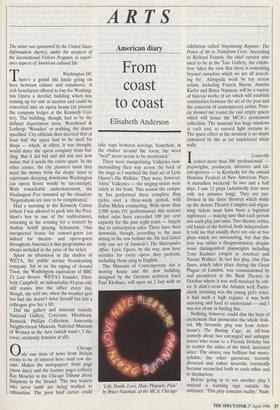

There were trampolining Valkyries sum- mersaulting their way across the back of the stage as I watched the final act of Lyric Opera's Die Walkiire. They were, however, `extra' Valkyries — the singing sisters were safely at the front. This season the compa- ny has performed three complete Ring cycles over a three-week period, with Zubin Mehta conducting. With more than 3,500 seats (91 performances this season) ticket sales have exceeded 100 per cent capacity for the past eight years — largely due to subscription sales. These have their downside, though, according to the man sitting in the row behind me. He had lasted only one act of Janacek's The Makropulos Affair. Lyric Opera, by the way, now have surtitles for every opera they perform, including those sung in English. The Museum of Contemporary Art is moving house and the new building, designed by the German architect Josef Paul Kleihues, will open on 2 July with an `Life, Death, Love, Hate, Pleasure, Pain' by Bruce Nauman, at the MCA, Chicago exhibition called Negotiating Rapture: The Power of Art to Transform Lives. According to Richard Francis, the chief curator who used to be at the Tate Gallery, the exhibi- tion 'takes the view that there is something beyond ourselves which we are all search- ing for'. Alongside work by ten recent artists, including Francis Bacon, Anselm Kiefer and Bruce Nauman, will be a variety of historic works of art which will establish continuities between the art of the past and the concerns of contemporary artists. Fran- cis showed me round the vast empty spaces which will house the MCA's permanent collection. The museum has huge windows at each end, so natural light streams in. The space effect at the moment is no doubt enhanced by the as yet unpictured white walls.

Louisville I joined more than 300 'professionals' playwrights, producers, directors and tal- ent-spotters — in Kentucky for the annual Humana Festival of New American Plays. A marathon weekend. In two and a half days, I saw 12 plays (admittedly four were only ten minutes long). They are per- formed in the three theatres which make up the Actors Theatre Complex and organ- ising tickets must have been a logistical nightmare — making sure that each person saw each play just once. Two theatre critics, old hands of the festival, both independent- ly told me that usually there are one or two plays which are outstanding, but that this year was rather a disappointment, despite some distinguished playwrights including Tony Kushner (Angels in America) and Naomi Wallace. In fact her play, One Flea Spare, which takes place during the Great Plague of London, was commissioned by and premiered at the Bush Theatre in October where it was well received by crit- ics. It didn't cross the Atlantic well. Partic- ularly irritating was the young girl's voice: it had such a high register it was both annoying and hard to understand — and I was not alone in finding this.

Nothing, however, could dim the buzz of excitement that permeates the whole festi- val. My favourite play was Joan Acker- mann's The Batting Cage, an off-beat comedy about two estranged and unhappy sisters who come to a Florida Holiday Inn to scatter the ashes of the third, deceased sister. The sisters, one brilliant but mono- syllabic, the other garrulous, recently divorced and rather neurotic, eventually become reconciled both to each other and to themselves.

Before going in to see another play I noticed a warning sign outside the entrance: `This play contains nudity.' Nudi- ty (in this case only semi-nudity) clearly worries Americans more than swearing (of which there was a lot).

Seattle Microsoft, Boeing and Starbucks Cof- fee all have their headquarters here; this, I was told on many occasions, underlines the fact that Seattlers demand quality. Their arts institutions are respected nationally and they now want international recogni- tion. Seattlers are also very well-behaved, as this probably apocryphal story illus- trates. A police chief couldn't decide whether to take up a job offer in Seattle. He wandered round the city late at night in the pouring rain trying to make up his mind. He watched a pedestrian in the deserted streets waiting patiently for the traffic lights to change, and who only crossed the street when the 'walk' sign appeared. The man took the job and moved to Seattle.

Most of the major arts institutions seem to be on the move (or have just moved) too. Robert Venturi (Sainsbury Wing, National Gallery) designed the new Seattle Art Museum which opened in 1991 and Pacific Northwest Ballet completed its new rehearsal studios and school building in 1994. (I know the Nutcracker is a popular ballet, but I was astonished to be told that it is performed every year throughout December and that PNB gets a third of its annual income from it.) It shares its per- forming stage with Seattle Opera (famed for its Ring cycle), but has an eye on a nearby building which it could convert. The Seattle Symphony plans to build a new con- cert hall opposite the Seattle Art Museum and A Contemporary Theatre is converting a former men's club into three new the- atres (as I clambered round the building in my hard hat I was assured that, despite appearances, it is on schedule to open in September).

I picked (unintentionally) singles night (cake, wine and music beforehand) to see Seattle Rep's Psychopathia Sexualis by John Patrick Shanley — an amusing story of a man's hang-up about his father socks, with- out which he cannot make love. The Rep, naturally, has a campaign to raise money to complete a small second stage in the same theatre complex.

Salt Lake City It depends on who you talk to, but Mormons make up somewhere between 40 and 50 per cent of the city's population. Their influence reaches everywhere — not least to the 'dry' laws of Utah. I truly felt like an alcoholic when I tentatively asked for a glass of wine with dinner. The waitress whipped out of her pocket a card listing the wines she had: one red, two white. Nowhere on the main menu was there any mention of nine gallons of ice-cream per person per year.

An hour's drive away from what must be one of the most beautifully sited cities in the world is Brigham Young University in Provo, where 97 per cent of the 12,000 stu- dents are Mormon. BYU is a huge campus and I was taken round the sprawling acres in an electric golf buggy, scattering stu- dents as we went. My suggestion (which wasn't meant to be offensive) that perhaps this made for a rather narrow perspective was firmly (and extremely politely) dis- missed because, I was told, the high pro- portion of foreign students made for a hugely varied environment. Point taken. Dance looms large in the prospectus and students can 'major' in dance education (4,000 students have enrolled in the ball- room dance division).

Back in Salt Lake City I dropped in on the world-renowned Tabernacle Choir who were practising for Easter Sunday services. The public can walk in and out of the rehearsal at will, a marvellous evening's entertainment — for free, too.

Given a conducted tour of the Museum of Church History and Art, which contains works primarily by or about Latter-day Saints. Many of the first artists to come to Utah at the beginning of the 19th century were from Scandinavia and Britain. What some of the pictures may lack in artistic merit is more than made up for if they are seen as chronicles of the whole history of Mormonism.

Took a day out and drove to the Wasatch mountains, half an hour's drive to the east of the city where the 2002 Winter Olympics will be held; then drove to the great salt lake itself (very big and very smelly).

Albuquerque Was quite unprepared for this city: it is far larger than I expected, not because of its population but because of the distance it spans, straggling on and on into the desert. The Maxwell Museum of Anthropology at the University of New Mexico concen- trates on the native cultures of the south- west. Saw a huge collection of pottery, carvings, baskets, blankets and so on made by American Indians. Santa Fe, some 55 miles away, is much easier for the tourist (i.e. me) to get to grips with, though Albuquerqueans are quick to disparage their neighbour: too expensive alcohol. I don't know if there's a One of a pair of chicken cups, Ming dynasty, in connection, but Utahns eat nearly Splendours of Imperial China at the Metropolitan, New York and too many tourists (probably true in high season). Nearly all the buildings are of the same bitter orange colour and made of adobe (unburnt brick, dried in the sun). Apart from looking attractive, Santa Fe also has a centre (somewhere I never found in Albuquerque) and a clutch of museums.

The (partly) open-air opera house miles from anywhere with stunning views over the desert — was closed, but, I was told, although the opera season coincides with the rainy one, if you bring a macintosh and hat (umbrellas are banned) you don't tend to get too wet too often (and the uncovered seats are cheaper too).

ANew York rived with end-of-term (or was it end-of-holiday?) feelings: only two days left in America.

To the Metropolitan Museum to see Splendours of Imperial China. These trea- sures were taken by Chiang Kai Shek to Taiwan when he fled China: silk hanging scrolls and screens, fine porcelain, exquisite carved jade and treasure boxes (there are so many items, most of them looking so very delicate, that it's hard to believe that he left in a hurry — unless he was a bril- liant packer).

Spent my last day gallery-hopping: MoMA, Guggenheim, Whitney and Frick. Overwhelmed by the Whitney's Kienholz retrospective. Loved (probably the wrong word) it. From the late 1950s, Edward Kienholz (who died in 1994) produced original freestanding sculpture, often tak- ing the form of large stage-set scale instal- lations. Part spoof, part indictment of the pretentiousness of the art world, 'The Art Show' (1963-1977), for instance, constructs a gallery opening with a number of life-size figures standing around the gallery talking, drinking and looking at one another as well as the pictures. Instead of mouths, the fig- ures have air-conditioning units on their faces and, when you push a button on the unit, pretentious remarks (hot air) are heard. Some of the other installations are truly horrific: 'The Illegal Operation', 1962, in which a sack of concrete is slumped over a chair, ripped open at the bottom, a filthy bucket positioned on the side and a dirty bedpan under the chair with surgical instruments sticking out . . . a seedy repre- sentation of a backstreet abortion. Found the exhibition (some 150 pieces in all) a revelation; it moves to Berlin next year after Los Angeles.

Five streets south at the Frick, the contrast was unsettling: masterpieces by Bellini, Constable, Turner, Frago- nard, Vermeer and so on. I'm not sure I saw the museums in the right order.

My last night (part of) was spent at the top of the Peninsula Hotel drink- ing cocktails and gazing out over Manhattan. Time to go home.

Elisabeth Anderson is arts editor of The Spectator.

Previous page

Previous page