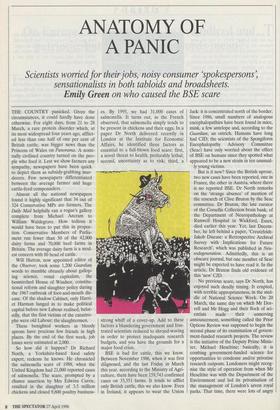

ANATOMY OF A PANIC

Scientists worried for their jobs, noisy consumer 'spokespersons, sensationalists in both tabloids and broadsheets.

Emily Green on who caused the BSE scare THE COUNTRY panicked. Given the circumstances, it could hardly have done otherwise. For eight days, from 21 to 28 March, a rare protein disorder which, at its most widespread four years ago, afflict- ed less than one half of one per cent of British cattle, was bigger news than the Princess of Wales on Panorama. A nomi- nally civilised country turned on the peo- ple who feed it. Lest we show farmers any sympathy, newspapers have been quick to depict them as subsidy-grabbing mur- derers. Few newspapers differentiated between the average farmer and huge cattle-feed compounders.

Almost all the national newspapers found it highly significant that 34 out of 324 Conservative MPs are farmers. The Daily Mail helpfully ran a rogue's gallery complete from Michael Ancram to William Waldegrave. How tedious it would have been to put this in propor- tion. Conservative Members of Parlia- ment run fewer than 50 of the 42,000 dairy farms and 70,000 beef farms in Britain. The average dairy farm is a mod- est concern with 80 head of cattle.

Will Hutton, now appointed editor of the Observer, took some 1,200 Guardian words to mumble obtusely about gallop- ing science, venal capitalists, the besmirched House of Windsor, constitu- tional reform and slaughter policy during the 1967 outbreak of foot-and-mouth dis- ease. Of the shadow Cabinet, only Harri- et Harman lunged in to make political capital before new Labour realised, belat- edly, that the first victims of the catastro- phe were old Labour: the slaughtermen.

These benighted workers in bloody aprons have precious few friends in high places. By the end of the first week, job losses were estimated at 2,000.

So how did it happen? Dr Richard North, a Yorkshire-based food safety expert, reckons he knows. He chronicled the salmonella scare of 1988, when the United Kingdom had 21,000 reported cases of salmonella. The scare, prompted by a chance assertion by Mrs Edwina Currie, resulted in the slaughter of 3.5 million chickens and closed 9,800 poultry business- es. By 1995, we had 31,000 cases of salmonella. It turns out, as the French observed, that salmonella simply tends to be present in chickens and their eggs. In a paper Dr North delivered recently in London at the Institute for Economic Affairs, he identified three factors as essential to a full-blown food scare: first, a novel threat to health, preferably lethal; second, uncertainty as to risk; third, a strong whiff of a cover-up. Add to these factors a blundering government and frus- trated scientists reduced to shroud-waving in order to protect inadequate research budgets, and you have the grounds for a major food crisis.

BSE is bad for cattle, this we know. Between November 1986, when it was first dignosed, and the last Friday in March this year, according to the Ministry of Agri- culture, there have been 159,743 confirmed cases on 33,351 farms. It tends to afflict only British cattle, this we also know. Even in Ireland, it appears to wear the Union Jack: it is concentrated north of the border. Since 1986, small numbers of analogous encephalopathies have been found in mice, mink, a few antelope and, according to the Guardian, an ostrich. Humans have long had CJD; the scientists of the Spongiform Encephalopathy Advisory Committee (Seac) have only worried about the effect of BSE on humans since they spotted what appeared to be a new strain in ten unusual- ly young victims.

But is it new? Since the British uproar, two new cases have been reported, one in France, the other in Austria, where there is no reported BSE. Dr North remarks on the `strange absence' of mention of the research of Clive Bruton by the Seac committee. Dr Bruton, the late curator of the Corsellis Collection brain bank, of the Department of Neuropathology at Runwell Hospital in Wickford, Essex, died earlier this year. Yet, last Decem- ber, he left behind a paper, `Creutzfeldt- Jakob Disease: a Retrospective Archival Survey with Implications for Future Research', which was published in Neu- rodegeneration. Admittedly, this is an obscure journal, but one member of Seac might be expected to have read it. In the article, Dr Bruton finds old evidence of this 'new' CJD.

No previous scare, says Dr North, has enjoyed such deadly timing. It erupted, with terrible appropriateness, in the mid- dle of National Science Week. On 20 March, the same day on which Mr Dor- rell and Mr Hogg and their flock of sci- entists made their unnerving announcement, something called the Prior Options Review was supposed to begin the second phase of its examination of govern- ment-funded research projects. The review is the initiative of the Deputy Prime Minis- ter, Michael Heseltine; basically, it is combing government-funded science for opportunities to condense and/or privatise research outposts. Londoners might recog- nise the style of operation from when Mr Heseltine was with the Department of the Environment and led its privatisation of the management of London's seven royal parks. That time, there were lots of angry gardeners. This time, it is scientists and support staff who are cross.

One candidate for privatisation is the Veterinary Laboratories Agency, which now includes the Central Veterinary Labo- ratory in Weybridge which discovered BSE. The centres of BSE research, the Institute of Animal Health at Compton, Berkshire, and its Edinburgh office, the Neuropatho- genesis Unit (NPU), are also under scruti- ny. While the Institute director, Professor John Bourne, says that no BSE research would be affected, the union representing his staff has a different view: Nigel Titchen, the president of the union's Science Group, says, 'Of 520 staff, 61 have been made redundant since Christmas and that's in addition to 100 redundancies over the last eight years.' David Luxton, another union officer, remarks bitterly that the last time the NPU was hit was in 1990, as BSE was peaking in British dairy herds.

According to Tom Wilkie of the Inde- pendent, one of the few journalists on that paper to write with dignity and under- standing about BSE, the NPU has its crit- ics. 'It is an open secret in the scientific community that for nearly a decade the period before the outbreak of mad cow disease — the NPU simply marked time scientifically by failing to appreciate the relevance of modern molecular biolo- gy — gene-splicing and genetic engineer- ing.' In plain English, they should have been trying their damnedest to give trans- genic mice with human DNA a good dose of BSE.

In 1994, four years after the Ministry of Agriculture turned down an offer from an American scientist to do just that, Dr John Collinge, a clinical neurologist from the Prion Diseases Group at St Mary's Hospi- tal Medical School, began a similar experi- ment. This unit has been populated by unhappy scientists and suffered a dramatic drain to the United States and Australia. The good news is that so far Dr Collinge's transgenic mice have not contracted the `new' CJD from BSE.

So, we have the spectacle of the Agricul- ture and Health Ministers hiding behind their scientists. The resounding irony is that cases of CJD are falling, not rising. In 1994, there were 50 cases, in 1995 only 40.

Dr North damns British research into BSE as 'bad science' from beginning to end. It was certainly fast science. Within two years of BSE being diagnosed, the Ministry of Agriculture elected to believe that it came from infected feed, yet failed to conduct tri- als on cattle. Similar trials begun in the Unit- ed States in 1990 have failed to produce BSE. Dr North claims that other possible causes — including a genetic predisposition to BSE due to widespread use of artificial insemination in dairy herds, Maff-ordered dousing of dairy herds with the pesticide Phosmet in 1984, depleted resistance in ani- mals due to over-milking — were never satis- factorily explored.

Enough science, at least enough real sci- ence. The most shameful aspect of the BSE crisis must have been the alacrity with which the press turned, unquestioningly, for easy quotes. On day three of the crisis, Sheila McKechnie, the new director of the Con- sumers' Association, thought nothing of leaping into the fray and advising worried consumers that they had `no choice' but to stop eating beef. Every news gatherer duly repeated her. The CA was widely described as a 'watchdog' even though it is, in fact, mainly a guide and magazine publisher. It has no independent research on BSE and its laboratory tests domestic appliances.

Seac scientists almost immediately went to ground, leaving a small but vocal trio of doomsayers gabbling to the press: Dr Richard Lacey appeared in the Daily Mirror, the Guardian, the Independent, the Independent on Sunday, the Daily Mail and more. This is the same Richard Lacey who thought up the Observer's lurid 'euthanasia clinic' scenario, the same Richard Lacey who predicted millions of salmonella poi- sonings. It is almost as if he somehow wants us to be sick, and that his frustration mounts as most of us remain stubbornly healthy. Few could have missed Harash Narang, the Newcastle-based microbiolo- gist who insists controversially that BSE is the result of a 'slow virus'. Sacked by the Government's Public Health Laboratory Service in the 1980s, he is now funded by a north-eastern businessman who reputedly made his millions from prawns. Dr Narang claims to have developed a urine test for both BSE and CJD, which the Government won't use. He alludes to a conspiracy against him, pointing out that his car's tyres have been slashed and his house burgled.

Last, but not least, there is Dr Stephen Dealler, the registrar from Burnley Gener- al Hospital, the abattoir policeman whose fury that cattle get sick is constantly inten- sified with the long-established fact that we eat them. He would be a logical source for anonymous estimates throughout the press that we may have consumed between 1 and 1.8 million cattle incubating BSE, even though Britain has had less than 160,000 confirmed cases and only 85 per cent of cattle suspected of the disease actually prove positive after they have been destroyed.

The latest reports suggest that BSE may have come from hay mites carrying the rogue prion protein. This is feasible and would tally with knowledge long held by sheep farmers: scrapie, the oldest recognised transmissible spongiform encephalopathy, is present in pasture, and, while it has been hard on sheep, so far it hasn't killed 500,000 of us. As for to human health, there is only one scientific certainty about the business. At some point or other, we are all going to die.

From 1988 until last month, Emily Green was a food writer for the Independent. She resigned over its coverage of BSE.

Previous page

Previous page