Old Ireland over here

Roy Kerridge

' ure it's great to see you,' says Hogan the park keeper from County Mayo, a mischievously genial expression on his rug- ged face.

Hogan arrived in England in time to build Harlow New Town, and he has always favoured Cambridgeshire and Essex, revell- ing in the sight of flat countryside.

`Back home in Mayo, wherever I'd look, I'd see them pesky owd mountains,' he ex- plained to me earnestly. 'We'd go out with our dogs after hares, but it was awful slippy and muddy, d'you see? I was glad to get to the east of England, where everything's beautiful.'

Building Harlow and them constructing motorways might seem to be somewhat reprehensible on the part of a lover of our eastern counties, but Hogan managed to get a great deal of enjoyment and excitement out of it. He met men from all over Ireland and a good many Irish women too, who had come over prospecting for husbands.

`The hostel for navvies was open all night, d'you see, and no sleep could be got, what with the playing cards and discussing winners, d'you see? Men would be walking in and out all the time. Even women came there sometimes. Some of our belongings kept disappearing, and one of the lads told the priest. When we were all at work, the owd priest came back unexpected-like and caught the thief just as he was taking a man's watch.

'There was a fine, big girl came there once, and I thought she'd make a fine wife, d'you see? But to my surprise she told me she was a prostitute. The last time I ever did see her, she was sitting on a bench, blue with cold, and I bought her a cup of tea. Another girl came up to a friend of mine and offered to marry hint "'Give me all your money every week and I'll save for two years and then we'll get married," she says.

`So that's what he did, d'you see? And the upshot of it was that after two years had nearly gone by, she sent herself a letter say- ing "Come to Dublin urgently on familY business" and showed it to him. So off she went, and never returned and years later so- meone told my friend he'd seen her in Dublin with a husband and three children, d'you see? Ever since that day my friend vowed he would spend all his money on get- ting drunk and leave the girls alone. So he never married at all.

'After that I had some fine lodgings in Harlow with a good landlady. We had fine big breakfasts, bacon, fried potatoes and cabbage, the same as the Pope eats. On Fridays we had fish. When I was in Ireland, no café would serve meat on a Friday, d'you see? And then one of the Popes changed it all, and said that meat could be, ate on a Friday itself after all. "Sure, the Pope must have been drunk when he said that," my friends all agreed, but it was made into law nevertheless. `One morning a new man by the name of Kelly would not go out to work with the rest of us. "Go out with the boys," the landladY, says, "and they'll find work for you.', "I'm not interested in that kind of work,' he says. "Did you read in the paper of an armed robbery at the post office and a burglary after that?" he says. "I did," she says. "Well," he says, "that was me in the papers." "Get out and pack your bag and leave!" she says, so he had to go. `Ah, you get some queer people around, to be sure. Back home in Mayo, I remember a man came around from the Government giving out blind pensions, and knocked at

the door of a neighbour of mine. your name Macaffery?" he says. "It is," he replies. "Well, would you be after signing here for the blind person?" he tells him.

`Macaffery had eyes like a fox, d'you see, but he pretended he couldn't see at all well, and signed all over the paper in the wrong Places. So the man took his paper, and then asked the way to the next village. "See that red and white ox on the hill there? It's beyond that," Macaffery replies. "You can see better than I can!" the government man says, and so Macaffery lost his chance of a Pension, d'you see, and he nearly had it got.'

Hogan's great pleasure is to go with his Wife to a pub where Irish music is played. His children are now grown up and gone into the world but I find it an endearing quality of the Irish in England that they can so often combine a happy united family life with a relish for drinking, dancing and gambling that in any other people would destroy all hope of domesticity. I remember Cosy evenings in a Londdn Irish household with six children, Tara, Colleen, Pat, Came], Rory and Liam. Most of this English-born brood went through a Mass- going phase and then paired off with other London Irish to live as unmarried couples in flats. Their parents, who railed at `Priestcraft', accepted this cheerfully and doted on their grandchildren.

No friend to anti-clericalism, I was rather shocked by the greeting a priest gave to two girls straight off the boat, who knew nobody in England. He simply gave them a huge collecting box and told them to ask all their friends to put money in it for him to collect once a week, The girls agreed demurely, but in fact ran wild for a time, neglecting the church. One of them even- tually married a Chinaman. Unlike this priest, I would extend a warm welcome to the Irish, a people who are so different from the English and yet so similar. If I met an Irishman at the uttermost ends of the earth, I would hail him as a fellow countryman but keep him off the subject of politics.

Many Irish pubs in England treat rules and regulations with an airy carelessness, closing when they please, allowing small children to accompany their parents, and frequently holding lotteries. Once I saw a man with a winning ticket being invited to choose one of three envelopes. One con- tained two pounds, the other three pounds and third £100. Nervously, the man tore an envelope open. 'The tension mounts!' said the compere truthfully. Applause broke out all over the pub as the lucky man held out a .hundred pounds.

Irishmen have the happy and un-English knack of retaining their flamboyance and improving on their rambling conversation as they rise in the social scale. Near Notting Hill Gate, in an oak-panelled saloon bar, I was privileged to meet a former alderman and trade unionist from Cork. With ponderous dignity, he learned precariously back in his wooden chair as he commanded another Irishman, a tall, mischievous 72-year-old known as the Bard of Kens- ington, to read to him from a slim, leather- bound volume of Blake. With his red nose, bucolic features, over-stretched yet rumpl-

ed and crumb-spattered waistcoat and stripy trousers, the tipsy alderman looked the im- age of materialism. Yet disjointed poetic phrases burbled out of him, and tears flow- ed from his eyes as he urged the Bard, in a port-thickened throaty voice, 'Give me, more poetry for my delectation'. 'This pub is my drawing room,' announced the Bard, closing his book, smoothing his snow-white locks and accepting a glass of whiskey. 'I shall now proceed to my living room.' With dignity he walked down the hill towards another pub, holding his full glass carefully in his hand. So if your pub has an extra glass at closing time, the mystery is now ex- plained.

ne of my favourite London Irish pubs, ‘,.../set very much in the workaday world of railway and factory, is the Willesden Junc- tion, near the wondrous station of that name. Last year I went there to hear the popular Irish singer Betty Reilly from Sligo. A vivacious dark-haired woman, she used her microphone cable as a skipping rope as she sang a breathless version of 'The Good Old Mountain Dew'. Unfortunately the long, dark dance hall at the back of the pub had no bar in it, and so was almost empty. Betty popped her head into the old- fashioned bar room with its scenes of Killarney superimposed on mirrors and bordered by painted shamrocks, and ap- pealed for listeners and dancers. When satisfied with the size of her audience, she sang another ballad, 'The Wife of Wex- ford', with its astonishing advice to young housewives: 'Eggs, eggs and marrowbones Will make your old man blind / But if you want to drown him, you must push him from behind.'

Now all is altered at the Willesden Junc- tion, for last 31 March a new combined saloon-bar and dance hall was opened, a mass of bright lights, red plush and flock wallpaper with a smaller dancing-space than before. It was opened by Hurricane Higgins, a quietly-spoken snooker cham- pion, who slept off the effects of his fatigu- ing journey in a bedroom above the bar, before descending to pull the first pint of Guinness and sign autographs. Lucky holder of this first glass of Guinness was Thomas Germaine from Dublin, who had laid the carpets in the pub, and whose triumph was shared by his wife and three small sons. Guinness has a special meaning for the Irish. They seem to look on it with patriotism as the symbol of their nation, as the Welsh do their language.

See a newly-drawn glass of Guinness, at first a brown swirling mass, without form and void. Then a shiny ebony blackness forces the white cream to the top, where it brims over the rim of the glass, and you can understand the faraway spiritual look in the eyesrof the Irish who have long gazed on scones such as this.

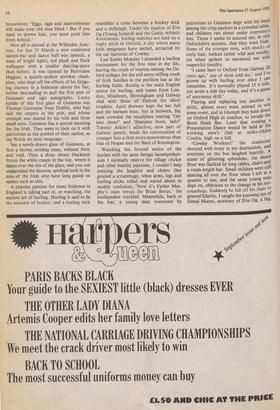

A popular pastime for many Irishmen in England is taking part in, or watching, the ancient art of hurling. Hurling is said to be the ancestor of hockey, and a hurling stick resembles a cross between a hockey stick and a shillelagh. Under the aupices of Eire Og (Young Ireland) and the Gaelic Athletic Association, hurling matches are held on a rugby pitch in Oxford, a city where many Irish emigrants have settled, attracted by the car factories of Cowley.

Last Easter Monday I attended a hurling tournament for the first time in my life, leaving the crush of tourists among the Ox- ford colleges for the still more stifling crush of Irish families in the pavilion bar at the hurling fields. Ruislip is the main English centre for hurling, and teams from Lon- don, Middlesex, Birmingham and Galway vied with those of Oxford for silver trophies. April showers kept the bar full and the barmen busy, but in between, big men crowded the touchlines roaring 'Get into them!' and 'Hammer them, lads!' Tommy Atkins's adjective, now part of Galway speech, made the conversation of younger fans a little more monotonous than that of Hogan and the Bard of Kensington.

Watching the fevered antics of the hurlers with the same benign incomprehen- sion I normally reserve for village cricket and other healthy pastimes, I couldn't help noticing the laughter and cheers that greeted a scrummage, when arms, legs and hurling sticks rolled and waved about in muddy confusion. 'Now it's Father Mur- phy's team versus the Brian Borus,' the loudspeaker crackled. Meanwhile, back at the bar, a young man overcome by patriotism to Guinness slept with his head among the crisp packets at a crowded table, and children ran about under everyone's feet. Those I spoke to assured me, in rich Oxfordshire accents, that they were Irish. Some of the younger men, with shocks of curly hair, looked rather wild and woolly, yet when spoken to answered me with respectful timidity.

'I came here to Oxford from Galway 20 years ago,' one of them told me,' and I've grown up with hurling ever since I can remember. It's normally played 15 a side, not seven a side like today, and it's a game of enormous skill.' Playing and replaying one another in shifts, almost every team seemed to win some event, and in triumph they bore down on Oxford High in coaches, to invade the Berni Steak Bar. Later that evening a Presentation Dance would be held at the working men's club at strike-ridden Cowley, high on a hill. `Cowley Workers!' the conductor shouted with irony at my destination, and everyone on the bus laughed heartily. A scene of glittering splendour, the dance floor was flanked by long tables, chairs and a room-length bar. Small children were still dancing all over the floor when I left at a quarter to one, and the same young man slept on, oblivious to the change in his sur- roundings. Suddenly he fell off his chair to general hilarity. I caught the knowing eye of Donal Moore, secretary of Eire Og, a big, grey-haired man who had been liberally handing out cellophane-wrapped trophies from the stage a moment before. When I asked him about the history of hurling, he replied with the eloquence of the alderman, hero that the first hurler was 'the Irish nero Cuchulain, who, thousands of years ago, hit a golden ball all the way from bublin to Galway.' Organised hurling, however, will celebrate its centenary next year, when teams from all over England will return to Ireland for a grand celebratory tournament. I said goodbye to the secretary and to Mick

Muller the chairman, and walked back to my hotel at the bottom of Cowley Road, my head full of Irish tunes. One in par- ticular, a ploughman's lament, seemed to sum up the ambivalent attitude of our fellow Britons, the Irish, towards England.

'I wish the Queen of England would write to me in time, And place me in some regiment, all in my youth and prime.

I'd fight for dear old Ireland from dusk until the dawn, And never more return again to plough the Rocks of Bawn.'

Previous page

Previous page