PARTING IS SUCH SWEET SORROW

Hard though it is to believe, many Germans

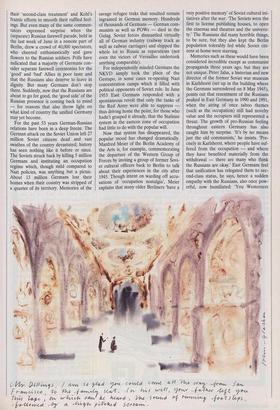

Berlin `MY BROTHER in Moscow needed some spare parts for his car.' The young Russian lieutenant grins. Behind him half a dozen of his men, stripped to their Red Army breeches and boots, slop through the mud around what was once a red Opel Accord, pushed over on its side and stripped of every detachable part. Now they are set- ting to work on the carcass. It was the sound of their sawing — old-fashioned, muscle-powered sawing — that awakened our curiosity and drew us to this spot.

No, the lieutenant continued, he wouldn't stay here if he had the choice. German labourers have built him a fine apartment back in Kursk— in exchange for East Germany, the Germans are build- ing homes for East Germany's former Russian occupants — and he's looking for- ward to moving into it. The thought of his new home is surely more enticing than this apocalyptic backdrop of courtyard scav- engers. Garbage is everywhere — old food, scraps of clothing, discarded bicy- cles. Every window in the apartment build- ing has been broken.

`Here' is the Berlin suburb of Karl- shorst. In 1945, soon after the Russians 'US Coastguard — freeze." arrived, what had once been a well-to-do capitalist suburb became the headquarters of Stalin's occupation government, the Soviet Military Administration in Germany (SMAG). It was also here, five years later, that the occupiers chose to pass authority to Otto Grotewohl, the first president of the German Democratic Republic — leav- ing little doubt about the source of Grote- whol's legitimacy.

Now the GDR has disappeared into his- tory, and its sponsors will be following suit on 31 August, when Colonel General Matvei Burlakov, commander of the West- ern Group of the Soviet Armed Forces, boards a plane for Moscow after bidding farewell to the last Russian troops on Ger- man soil. Poles, Czechs and Hungarians have already celebrated the withdrawal of Russian troops from their own countries with ill-concealed joy. One might expect the Germans to do the same.

But walk through Karlshorst, the part of Berlin that has experienced Russian occu- pation more directly than any other, and you will hear a different story. A middle- aged fireman told me how he would miss the Russians: 'It wouldn't bother me at all if they stayed.' He had always got along fine with the Russians ever since he was a child, when they set up a command post in his house at the end of the war. 'I tended their pigs and they gave me food in return. The Russians are always especially good to children.' They had also offered Berliners plenty of good meaty culture, none of that light-headed American stuff. 'Russian cul- ture is much closer to me somehow.' A woman standing behind him nodded enthu- siastically. What would she miss when the Russians left? 'I don't know. That Slavic soul, I suppose.' Then she hummed a few bars of a vaguely balalaika-compatible melody.

Among those caught off guard by such sentiments is Chancellor Helmut Kohl, who presumably thought he was following the public mood when, earlier this summer, he insisted upon organising separate farewell ceremonies for the Russians and the three western Allies. Most of the resulting commentary dwelt on Russian resentment toward what they considered their 'second-class treatment' and Kohl's frantic efforts to smooth their ruffled feel- ings. But even many of the same commen- tators expressed surprise when the (separate) Russian farewell parade, held in the last week of June in a remote part of Berlin, drew a crowd of 40,000 spectators, who cheered enthusiastically and gave flowers to the Russian soldiers. Polls have indicated that a majority of Germans con- sider separate farewell ceremonies for the `good' and 'bad' Allies in poor taste and that the Russians also deserve to leave in dignity. But many Germans don't stop there. Suddenly, now that the Russians are about to go for good, the 'good side' of the Russian presence is coming back to mind — for reasons that also throw light on what kind of country the unified Germany may yet become.

For the past 53 years German-Russian relations have been in a deep freeze. The German attack on the Soviet Union left 27 million Soviet citizens dead and vast swathes of the country devastated; history has seen nothing like it before or since. The Soviets struck back by killing 5 million Germans and instituting an occupation regime which, though mild compared to Nazi policies, was anything but a picnic. About 13 million Germans lost their homes when their country was stripped of a quarter of its territory. Memories of the savage refugee treks that resulted remain ingrained in German memory. Hundreds of thousands of Germans — German com- munists as well as POWs — died in the Gulag. Soviet forces dismantled virtually all of German industry (railway track as well as railway carriages) and shipped the whole lot to Russia as reparations (not even the victors of Versailles undertook anything comparable). For independently minded Germans the NKVD simply took the place of the Gestapo, in some cases re-opening Nazi concentration camps which it filled with political opponents of Soviet rule. In June 1953 East Germans responded with a spontaneous revolt that only the tanks of the Red Army were able to suppress thus driving home the point, for those who hadn't grasped it already, that the Stalinist system in the eastern zone of occupation had little to do with the popular will.

Now that system has disappeared, the popular mood has changed dramatically. Manfred Meier of the Berlin Academy of the Arts is, for example, commemorating the departure of the Western Group of Forces by inviting a group of former Sovi- et cultural officers back to Berlin to talk about their experiences in the city after 1945. Though intent on warding off accu- sations of 'occupation nostalgia', Meier explains that many older Berliners `have a very positive memory' of Soviet cultural ini- tiatives after the war: The Soviets were the first to license publishing houses, to open the cinemas and theatres and the universi- ty.' The Russians did many horrible things, to be sure, but they also kept the Berlin population tolerably fed while Soviet citi- zens at home were starving.

Memories such as these would have been considered incredible except as communist propaganda three years ago, but they are not unique. Peter Jahn, a historian and new director of the former Soviet war museum in Karlshorst (set up in the building where the Germans surrendered on 8 May 1945), points out that resentment of the Russians peaked in East Germany in 1990 and 1991, when the airing of once taboo themes (such as the occupation) still had novelty value and the occupiers still represented a threat. The growth of pro-Russian feeling throughout eastern Germany has also caught him by surprise. 'It's by no means just the old communists,' he insists. 'Pre- cisely in Karlshorst, where people have suf- fered from the occupation — and where they have benefited materially from the withdrawal — there are many who think the Russians are okay.' East Germans feel that unification has relegated them to sec- ond-class status, he says, hence a sudden empathy with the Russians, also once pow- erful, now humiliated: 'You Westerners have your first-class allies, we have our second-class allies.'

Suddenly, it has become chic to recall how Russians and Germans fought togeth- er against Napoleon. Don't forget that Bis- marck served as a diplomat in St Petersburg, I have been told; don't forget the Treaty of Rapallo or the Russian émi- grés who enriched Berlin during the 1920s. Don't forget how German intellectuals have always loved Dostoevsky and Tolstoy; don't forget that it was a Soviet culture officer who got Brecht his theatre in East Berlin when the East German Stalinists opposed the idea. Others put their money where their sympathy is: a Berlin furniture company is sponsoring a campaign for the adoption of house pets which have been left behind in Germany by Russian military families 'unsure that they will be able to keep their pets fed and housed when they return home to Russia'. Photographs of the cats (Puschkin, Igor, Inki etc) looking winsome appeared in a Berlin magazine.

Zyrill Pech, an East German preacher who headed the German-Soviet Friend- ship Society during the brief period when the GDR was trying to reform itself, recalled an old saying: 'When things are going well for relations between the Ger- mans and Russians, things will be good for both peoples; when relations between them are bad, things will be bad for both.' Germany, he insisted, is rediscovering its historical role as a middle power: It's wrong for Germany to orient itself solely to the West.' One wonders whether the Poles would agree.

Behind all this lies a deeper psychologi- cal fact: however unpleasant Russian occu- pation may have been, the Germans undoubtedly deserved it — and they know it. When Poles or Czechs or Hungarians look back on the Soviet presence, they see a foreign power that came to their coun- tries uninvited; when Germans look back on the Russian occupation, they see their own bad conscience. 'There were many people who understood why the Russians were here,' says Jahn. 'Not all, to be sure, but many.'

Indeed, as they prepare for their depar- ture, the last Russian soldiers are benefit- ing from one of those peculiar twists in the post-war German mind: the greater their historical distance from the war, the easier it becomes for Germans to wallow in their crimes. It is a form of masochism, crossed with guilt. For years West German intel- lectuals have cultivated their own brand of pushy philo-Semitism as a sort of compen- sation for the Holocaust; now, perhaps, a certain Slavo-philism will come as well.

Back in Karlshorst, apartment houses once occupied by Russian officers stand eerily ajar, inviting passers-by to walk in and survey the damage. In one deserted flat, its abandoned refrigerator still run- ning full blast, we found a few Russian military magazines strewn amid broken furniture and miscellaneous garbage. A recent issue of the journal Military Courier contained an article outlining the history of the Western Group of Forces under the headline, 'We have completed our mission in Germany and now return home with a sense of fulfilled duty.'

There were other comforts associated with the Russian presence in Berlin too. As one strolls through the rubble, it is worth remembering that Russian occupa- tion, paradoxically, relieved eastern Ger- mans of the responsibility for facing up to their past. By proclaiming obligatory socialist friendship at the point of the Red Army's guns, Russians allowed Easterners, `So it's decided, then. We'll eat Al Fresco.' at least, to 'forget' for just a little while longer, to put off indulging in the masochism enjoyed by their western cousins.

Now that alibi is gone. One resident of Karow, with the reflexive self-hatred char- acteristic of many a younger German, expressed mild horror at the thought of being left to face his countrymen on his own: 'When the Russians are gone, this will be just another dead German town.'

Previous page

Previous page