As truth will paint him, and as bards will not

Peter Hebblethwaite

SAINT PETER by Michael Grant Weidenfeld, £20, pp. 212 After Jesus' death Peter was recognised as the leader in the Christian community and the chief witness of the resurrection. Mentioned nearly 200 times in the New Testament, he appears in nine of its 27 books. No other apostle can match this.

Peter's 'image' shifts about. He is fisher- man, recipient of revelation, missionary, shepherd of the flock, confessor of the faith, teacher and finally martyr. These images provide the foundation for his hero- ic posthumous role.

Grant focuses on Peter's actual life, showing there is a middle way between fundamentalism and agnosticism. Some information about the historical Peter can be wrested from the Gospels. Symeon (Simon in Greek) came from Bethsaida in Galilee. Bethsaida means 'house of fish- ing': the industry flourished, salt making fish-pickling, and therefore exports, possi- ble.

The idea that Peter was rough-hewn and poor seems false. Though he had a Galilean accent, he must have been bi- or possibly tri-lingual to carry out first his business and then his mission. Peter answered Jesus's call and moved to Caper- naum, maybe because his mother-in-law was there. Jesus healed her fever. Peter's wife is a blank.

How Simon became Peter is the crucial episode of his life and subsequent destiny. To assign new names was a prophetic act. Grant does not know whether Tetros' (rock) refers to Peter's person or to his faith (an old Protestant-Catholic chestnut). The term was used, anyway, to stress rock- like permanence when appointing someone to a responsible position.

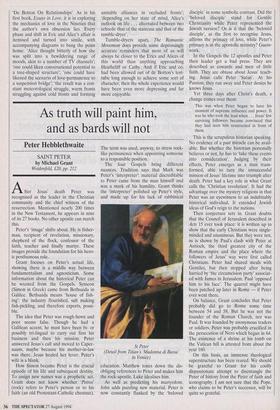

The four Gospels bring different nuances. Tradition says that Mark was Peter's 'interpreter': material discreditable to Peter came from the man himself and was a mark of his humility. Grant thinks the 'interpreter' polished up Peter's style, and made up for his lack of rabbinical St Peter (Detail from Titian's Madonna di Bassa' in Venice) education. Matthew tones down the dis- obliging references to Peter and makes him the rock-apostle. Luke idealises him.

As well as predicting his martyrdom, John adds puzzling new material. Peter is now constantly flanked by the 'beloved disciple' in some symbolic contrast. Did the `beloved disciple' stand for Gentile Christianity while Peter represented the Jewish version? Or is it that the 'beloved disciple', as the first to recognise Jesus, affirms the primacy of love, while Peter's primacy is in the apostolic ministry? Guess- work.

In the Gospels the 12 apostles and Peter their leader get a bad press. They are described as cowards and men of little faith. They are obtuse about Jesus' teach- ing. Jesus calls Peter 'Satan'. At his Passion, they run away and Peter denies he knows Jesus.

Yet three days after Christ's death, a change comes over them:

This was when Peter began to have his moment of supreme influence and power. It was he who took the lead when . . . Jesus' few surviving followers became convinced that they had seen him resurrected in front of them.

This is the scrupulous historian speaking. No evidence of a past miracle can be avail- able. But whether the historian personally believes or not, he has to 'take these events into consideration'. Judging by their effects, Peter emerges as a man trans- formed, able to turn the unsuccessful mission of Jesus' lifetime into triumph after death. Peter had a key role in what Grant calls the 'Christian revolution'. It had the advantage over the mystery religions in that Peter was an eyewitness to an indubitably historical individual. It extended Jewish ideas of God's reign to the nations.

Then conjecture sets in. Grant doubts that the Council of Jerusalem described in Acts 15 ever took place: it is written up to show that the early Christians were single- minded and unanimous. But they were not, as is shown by Paul's clash with Peter at Antioch, the third greatest city of the Roman empire and the place where the followers of Jesus' way were first called Christians. Peter had shared meals with Gentiles, but then stopped after being harried by 'the circumcision party' associat- ed with James in Jerusalem. Paul 'opposed him to his face'. The quarrel might have been patched up later in Rome — if Peter ever went there.

On balance, Grant concludes that Peter probably did go to Rome some time between 54 and 58. But he was not the founder of the Roman Church, nor was Paul. It was founded by anonymous traders or soldiers. Peter was probably crucified in the persecution of Nero which began in 64. The existence of a shrine at his tomb on the Vatican hill is attested from about the year 160.

On this basis, an immense theological superstructure has been reared. We should be grateful to Grant for his coolly dispassionate attempt to disentangle the Peter of history from the Peter of faith and iconography. I am not sure that the Pope, who claims to be Peter's successor, will be quite so grateful.

Previous page

Previous page