Exhibitions

Constable, a Master Draughtsman (Dulwich Picture Gallery, till 16 October)

Out of his time

Giles Auty

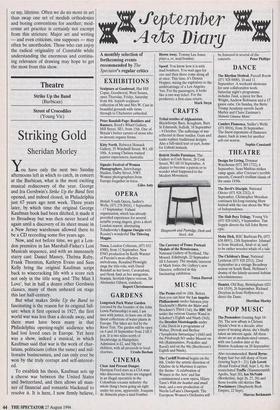

Driving a familiar route via Brixton and Denmark Hill to Dulwich Picture Gallery, I began to meet welcoming direc- tional signs when still two miles or more from my destination. Clearly Giles Water- field, director of the said gallery, is anxious that as many people as possible should see and enjoy Constable, a Master Draughtsman. Mr Waterfield is right to try to shepherd us in for this is an unusual, understated but deeply rewarding show, the exact opposite of the familiar modern museum blockbuster. Here the emphasis is on looking closely and pondering deeply, hardly the kind of responses required by many exhibitions which take place in our public galleries these days. What we get to see is some 80, mostly small, drawings from the hand of John Constable plus a few oth- ers by artists to whom the master in his youth may have owed something. What the exhibition really highlights is the purpose of drawing: especially timely since under- standing of drawing seems to have been lost, An excellent catalogue discusses, among other things, the drawing materials available from the end of the 18th-century. There is also an intense, intelligent but quite extraordinary essay by the artist and former critic, Patrick Heron. What are we to make of a tract entitled 'Constable: Spa- tial Colour in the Drawings'? As a some- time leading proponent of modernist values in art, Mr Heron argues his strange propositions with partisan fervour.

From his middle years, Constable drew with great naturalness and force, but those who have claimed to detect genius in his earlier work are either gifted with second sight or are limited in their understanding of drawing. Not all major artists develop at the same rate. Thus I do not think the early drawings of Lucien Freud, for instance, even hint at what was to come. What is apparent from this exhibition is that Con- stable learned gradually to use pencils to great expressive effect. Then as now, cer- tain basic principles can be taught, but the best of any artist lies in what he discovers for himself. Paradoxically, attempts at objective drawing from the motif often unleash the truest intimations of individu- ality. Just one of the delights of Constable's drawings is an absence of self-conscious- ness; in general he immersed himself opti- cally and philosophically in the pleasures and hidden resonances of landscape. Another remarkable aspect of Constable's drawings is their ability to convey a power- ful illusion of space and depth — an aspect of art destined to become anathema to rad- ical artists of more recent times who found themselves under the critical sway of such as Clement Greenberg — or Mr Heron. In `Salisbury from the road to Old Sarum' 1820, Constable delineates a flattish land- scape in pencil with great sensitivity and accuracy of scale. Few artists could begin to make such a drawing today because they have not been taught even the rudiments of observation, and will thus never experience the confidence and pleasure to be derived from such learning. A refined understand- ing of the seen is life-enhancing, which is yet another reason why help and encour- agement to this end should underpin art education from its earliest level.

What else can we learn from looking at a series of small drawings made more than a century and a half ago? Another aspect from which young artists in particular might benefit lies in Constable's skill and inventiveness in composition. This is also something Mr Heron points out in his essay. Some months ago I met a 40 year old landscape artist who had just enjoyed a successful debut in a West End art gallery. She had had some 25 years of art education in all — at schools, art colleges and as a postgraduate — yet had been taught little or nothing about composition which unsur- prisingly was the weakest aspect of her work. Often Constable used traditional devices for the division of available space, but just as frequently veered to the baroque — the apparently unbalanced, uneven or cantilevered composition where much of the pictorial weight is confined to one side.

Mr Heron writes correctly about pictorial tension and the excitement this can gener- ate in the viewer. He cites 'The Schooner Malta on Brighton Beach' as an example and sees parts of it as a forerunner of 'risky cubist-fauve triangulations'. Constable was indeed out of his time in his ability to reject pointless artistic conventions and one hopes Mr Heron is aware that the existence of the latter has hardly diminished in his, A Footbridge and Water-splash at Binfield, by John Constable or my, lifetime. Often we do no more in art than swap one set of modish orthodoxies and boring conventions for another; mod- ernist art practice is certainly not exempt from this stricture. Major art and writing — and even criticism, one supposes — may often be unorthodox. Those who can enjoy the radical originality of Constable while understanding the enormous and continu- ing relevance of drawing may hope to get the most from this show.

Previous page

Previous page