ARTS

Exhibitions

Neglected prophet

Giles Auty

Last week two events of unusual signifi- cance took place: the opening of what is, to date, the largest and most comprehensive exhibition of the art of David Bomberg and the launch of Modern Painters, a new quarterly journal of the fine arts, under the abrasive editorship of Peter Fuller. Bomberg, as most know by now, was an artist who suffered cruel and unjustified neglect. At the time of his death in 1957 his art was almost totally ignored, except by a small but loyal band of ex-students and other true believers. As more and more public and private money has been poured into the visual arts since the last war, it has become our foolish belief that such neglect has grown more or less impossible. This is far from the case. What our prevailing artistic climate of complacent pseudo- liberalism allied to massive expenditure encourages is an activity remarkably akin to one popular in the Holy Land about 2,000 years ago; one intends no sacrilege in calling it Messiah-spotting.

It is a game almost anyone, whether art scribe or Pharisee, can play with varying degrees of ineptitude or factional self- interest. Certainly it is a sport the metaphorical fat men of our museum hierarchies play regularly with scant regard for credibility; just one merit of the first issue of Modern Painters is the evisceration of the reputations of two or three notably false prophets by Robert Hughes and Roger Scruton. Two other bonuses of the magazine are what amounts to a mea culpa on the Arts Council's behalf from its former secretary general and a most thoughtful analysis of the strengths and minor weaknesses of Lucian Freud by Grey Gowrie. This eminence, only nomi- nally grise, shares my own belief in Freud's long-term importance, especially during a century remarkable for its increasingly empty fads.

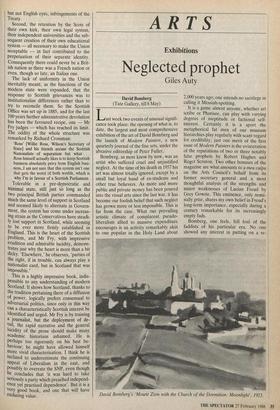

Bomberg, one feels, fell foul of the faddists of his particular era. No one showed any interest in putting on a re- David Bomberg's 'Mount Zion with the Church of the Dormition: Moonlight', 1923. trospective of his great body of works during his lifetime. How significant it is that five or more London dealers are able now to mount worthwhile shows of Born- berg's work concurrently with the present, magnificent Tate exhibition. Those still keen to collect may tour the following in the weeks to come: Boundary Gallery, Fischer Fine Art, Odette Gilbert, Bernard Jacobson and Gillian Jason. Some of these galleries have built large collections over a number of years. It is ironic that when the artist died there were no takers for paint- ings offered to museums at no more than £100 apiece. With drawings currently at £5,000 and more, we may appear now to be dancing on the artist's 30-year-old grave.

During his lifetime Bomberg had no regular dealer and found it almost impossi- ble to sell work; dispiriting poverty was one inevitable result, made bearable only by the spirituality and immigrant resilience of the artist's nature. After struggling up from a deprived East-End childhood to a place at the Slade — where he was a colleague of such as Gertler, Nevinson, Roberts, Spencer and Wadsworth — and short-lived notice and notoriety in his early twenties, Bomberg's artistic career suf- fered semi-permanent occlusion. The ear- ly, radical influences of Cubism and Vor- ticism gave way to the topographical per- ceptiveness of his paintings of Jerusalem in 1922-23 and these, in turn, to broader and more lyrical paintings of Toledo, Cuenca and Ronda from later in that decade.

Like many artists who underwent the horrors of the first world war, Bomberg emerged with a vision which found more suitable expression in the organic than the purely formal; the physical world they had so nearly lost assumed a heightened im- portance which returning servicemen would not deny again so readily. The scope of Bomberg's art laid him open to charges of inconsistency then and since, but to take this view is to evaluate art with an intellec- tual formalism the artist himself did not share. Although an inspiring instructor during one of his rare spells of teaching, at Borough Polytechnic, Bomberg was never the most verbally coherent of men about his areas of artistic passion.

In seeking to commune with the essence of the external world, Bomberg tried to distance himself from the inner, mechanis- tic hells which men have created for themselves in this century. Though far from cloudless, Bomberg's vision was fun- damentally affirmative almost to the end. The courage and vigour of his great paint- ings of Palestine, Spain, Cyprus and our own West Country prove the art of land- scape painting to have been far from merely derivative, let alone moribund, during this century. Even by itself, the centre core of the Tate Gallery exhibition stamps Bomberg as an artist of primary authority. London is indeed lucky that two such original and enduringly important artists as Bomberg and Lucian Freud should be on show simultaneously at major exhibition spaces which are devoted too often to the merely effete or ephemeral.

It is my hope that Modern Painters will provide a fresh forum for more open, intelligent and generous debate about the art of our time. Any antidote to the high-handed secrecy and power-mad exclu- sivity with which so many important deci- sions are habitually reached now in British and international art is overdue and wel- come. One cannot remind oneself too often that neglect of true talent is the sail but inevitable corollary of the overpraise of junk.

Previous page

Previous page