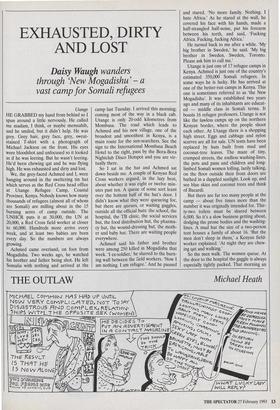

EXHAUSTED, DIRTY AND LOST

Daisy Waugh wanders

through 'New Mogadishu' - a vast camp for Somali refugees

Utange

HE GRABBED my hand from behind so I spun around a little nervously. He called me madam, I think, or maybe memsahib, and he smiled, but it didn't help. He was grey. Grey hair, grey face, grey, sweat- stained T-shirt with a photograph of Michael Jackson on the front. His eyes were bloodshot and unfocused so it looked as if he was leering. But he wasn't leering. He'd been chewing qat and he was flying high. He was exhausted and dirty and lost.

We, the grey-faced Achmed and I, were hanging around in the sweltering tin but which serves as the Red Cross head office at Utange Refugee Camp, Coastal Province, Kenya. Nobody knows how many thousands of refugees (almost all of whom are Somali) are milling about in the 15 burning acres of camp outside. The UNHCR puts it at 30,000, the UN at 20,000, a Red Cross field worker at closer to 60,000. Hundreds more arrive every week, and at least two babies are born every day. So the numbers are always growing.

Achmed came overland, on foot from Mogadishu. Two weeks ago, he watched his brother and father being shot. He left Somalia with nothing and arrived at the camp last Tuesday. I arrived this morning; coming most of the way in a black cab. Utange is only 20-odd kilometres from Mombasa. The road which leads to Achmed and his new village, one of the broadest and smoothest in Kenya, is a main route for the sun-searchers. See the sign to the International Mombasa Beach Hotel to the right, pass by the Bora-Bora Nightclub Disco Hotspot and you are vir- tually there. So I sat in the but and Achmed sat down beside me. A couple of Kenyan Red Cross workers argued, in the lazy heat, about whether it was eight or twelve min- utes past ten. A queue of some sort leant over the bottom half of the hut's door. I didn't know what they were queueing for, but there are queues, or waiting gaggles, outside all the official huts: the school, the hospital, the TB clinic, the social services hut, the food distribution hut, the pharma- cy hut, the wound-dressing hut, the moth- er and baby hut. There are waiting people everywhere. Achmed said his father and brother were among 250 killed in Mogadishu that week. 'I ex-soldier,' he slurred to the burn- ing wall between the field workers. 'Now I am nothing. I am refugee.' And he paused and stared. 'No more family. Nothing. I hate Africa.' As he stared at the wall, he covered his face with his hands, made a half-strangled half-noise, put his forearm between his teeth, and said, 'Fucking Africa. Fucking, fucking Africa.'

He turned back to me after a while. 'My big brother in Sweden,' he said. 'My big brother in Sweden. Sweden, Toronto. Please ask him to call me.'

Utange is just one of 17 refugee camps in Kenya. Achmed is just one of the country's estimated 350,000 Somali refugees. In some ways he is lucky. He has arrived at one of the better-run camps in Kenya. This one is sometimes referred to as 'the New Mogadishu'. It was established two years ago and many of its inhabitants are educat- ed — middle class in Somali terms. It boasts 16 refugee professors. Utange is not like the lawless camps up on the northern Kenyan border, where the people shoot each other. At Utange there is a shopping high street. Eggs and cabbage and nylon scarves are all for sale. UN tents have been replaced by huts built from mud and coconut-tree leaves. The maze of tiny, cramped streets, the endless washing-lines, the pots and pans and children and long- limbed Somali women lolling, lazily talking, on the floor outside their front doors are bathed in a dappled sunlight. Look up, and see blue skies and coconut trees and think of Bacardi.

But there are far too many people at the camp — about five times more than the number it was originally intended for. Thir- ty-two toilets must be shared between 6,000. So it's a slow business getting about, dodging the prone bodies and the washing- lines. A mud but the size of a two-person tent houses a family of about 16. 'But the men don't sleep in them,' a Kenyan field- worker explained. 'At night they are chew- ing qat and walking.' So the men walk. The women queue. At the door to the hospital the gaggle is always especially tightly packed. That morning an irritable old man stood blocking the entrance. He used a stick on the crowd in a fruitless attempt to push them back into the sunshine. Whether he was working for the hospital or simply protecting his own position was impossible to tell. Inside the hospital's one ward (it has nine beds) yet more women waited. Most of the patients are children with malaria. At the foot of each one sits a woman, some sort of rela- tion, who stares into space and waits — for the nurse, or the child's recovery, or its death, or instructions for the bed to be vacated. The only adult patient lay on his own in a corner. His wizened leg jutted half off the bed and he squinted. He had bone cancer.

Many refugees arrive at Utange with bullets still lodged inside their bodies. But such complaints by no means guarantee an appointment with a doctor. 'Of course not,' explained a middle-aged Danish nurse, who sat packing worm pills into small brown envelopes with the help of a mentally retarded young Somali boy. 'You can easily leave bullets in without having any problems at all.' The production of fraudulent doctor-appointment tickets has become something of an industry in the new Mogadishu. So has dealing in black market ration-cards.

`There are a few technical problems with food distribution,' a very polite teenage boy told me from behind his sock and clothes-peg stall. The UNHCR's refusal to issue any more full ration-cards, and the length of time which between applying for a short-term card and its arrival means people can be without food for two weeks or more. Cardless refugees must rely on the generosity of their neighbours.

Catherine Wandera, a Kenyan social worker who spends most of her time explaining to Somalis (via an interpreter) why they are not entitled to ration-cards/ medical attention/American passports, decided she'd had enough for one day, edged her way through the throngs outside her office and stood talking with a police officer.

Walking Somali men, for lack of any- thing better to do, came to a stop beside her and listened in. Another waiting gaggle emerged. They stood with heads to one side, looks of absent-minded curiosity on their faces, twigs of euphoria-inducing qat between their teeth. And there was some- thing about the way they stood there, unapologetic and relaxed, tickled, even, by their inactivity, or by the absurdity of their situation, that meant they emanated some sort of grace: a serene humility in the midst of so much nonsense.

The car which took me away from all this pulled up beside the Disco Hotspot signpost. Its driver, the Kenyan social worker, got out to wipe her feet on a tuft of grass.

`You stap in ah lot off shit,' she drawled as she climbed back in. `St-tt-t. The open sewahs.'

Previous page

Previous page