GOLDFINGER REVISITED

As crisis deepens at Lloyd's,

Martin Vander Weyer meets the

insurance market's most notorious outcast

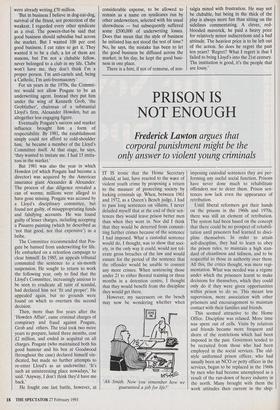

`THE MOST money we ever made in Lloyd's was out of war risks. We made masses . . . masses.' The last word comes out with a hiss of relish. The speaker is Ian Posgate, for 20 years the enfant terrible of the London insurance market and for a decade since then one of its pariahs.

As Lloyd's staggers on — £4.5 billion of accumulated losses, talk this week of 20,000 redundancies in member firms, the ragged chorus of bankrupt 'names' — it is ironic that the 60-year old Posgate, proba- bly the most successful underwriter in the market's history, should be an outcast. He is reduced to offering (from an office 200 yards from the market itself) well spiced comments on Lloyd's affairs to the press and advice to disgruntled names.

Perhaps surprisingly, Ian Posgate's belief in Lloyd's as an institution is unshaken. He quotes Pinero, in The Sec- ond Mrs Tanqueray: 'The future is but the

past, entered by another door.' Lloyd's, he says, still has 50 of the 100 best underwrit- ers in the world; it should trade out of its current difficulties, but on a reformed basis in which the minimum qualification for entry would be £500,000 of truly realisable wealth (as opposed to the current figure of £250,000, which can include a guarantee secured on the family home). The costs of underwriters' salaries and agents' commis- sions have to be squeezed down to com- pete with the big insurers outside. And unlimited liability — the mechanism which justified the tax advantages of Lloyd's membership in the 1960s and 70s and which, in effect, allowed Posgate to make his and other people's fortunes — is an anomaly which has had its day: 'Lloyd's is only 1 per cent of world insurance capacity now; if the other 99 per cent have gone for limited liability, they're unlikely to be wrong.'

Nowadays, Ian Posgate is all for tough management of the market, and blunt about recent changes: 'Lord [the recently departed chief executive] was a disaster, Coleridge [last year's chairman] did his best, but now he's discredited. Peter Mid- dleton [the new chief executive, a motor- cycling ex-monk] seems to be a good thing; this six-month moratorium on losses was the right thing to do and he went ahead and did it before the old guard could stop him. Hay Davison [the combative accoun- tant sent in by the Bank of England in 1983] was a good thing too, but in those days the old guard was still strong and they beat him. Now they're finished.'

What Posgate has always said he despised was the public-school smugness, the masonic back-scratching of what he calls 'the old guard', even though he is him- self unmistakably a figure from a past City age. Late back from a livery company lunch, he sprawls across a sofa with his spectacles perched at a comic angle on top of his domed forehead. The cut of his three-piece, double-breasted, slightly soup- stained suit suggests a backwards Conser- vative MP of the old school. The indiscreet, rascally charm of his conversation is redo- lent of a rather naughty character from an early Simon Raven novel — the sort you can't help but like.

And, like the best Raven characters, there is no doubt that, one way or another, he tempted fate. Known as Goldfinger (it was The Spectator which first put the nick- name in print, in 1971), Posgate used to control 20 per cent of Lloyd's marine insurance business. He made profits, usu- ally big ones, for his syndicates every year for more than 20 years. In his heyday he was one of the highest paid men in Britain — £800,000 per annum, astronomical for the 1970s, is the usual estimate — and he amassed personal wealth of tens of mil- lions.

His methods were ruthless in their sim- plicity but, one suspects, more rigorous in mathematical terms than his flamboyant manner suggested: a Cambridge graduate, he trained as an actuary before joining the market in the late 1950s. Lloyd's has been memorably dismissed by Max Hastings as the place where all the stupidest boys at school seemed to finish up; Posgate was far from stupid.

'I never knew much about analysing insurance risks, I just made a book. If claims came in, the premium went up. No claims, the premium went down. I was allowed to be a bookmaker on a huge scale, autocratic, absolutely outrageous.'

These principles were cheerfully applied to some of the highest-risk business in the

market. He made princely profits from kidnap cover, partly because the criminals often failed to collect the ransom when it was offered. In the Six Days War he cov- ered both El Al and Egyptair. He insured the Canberra when she went to the Falk- lands as a troop-ship. Where other under- writers might accept only a small percentage of any one risk, Posgate would take a minimum of 50 per cent, and often 100 per cent if he thought the business was good.

'In the Vietnam war we covered all the shipping in the Mekong — at 5 per cent of the cargo value per month. That's a huge premium. In wartime it's usually the Gov- ernment who's paying, and they tend to pay up whatever you ask. Well, suddenly some claims came in, so I put it up to 10 per cent a month and they still paid. Then the claims stopped, so we put it down to 5 per cent again. Every year the pattern was the same.

'Eventually one of those Foreign Office people — they're ghastly, you know explained it: in the rainy season, the Mekong's three miles wide, the shipping's perfectly safe out in the middle. But in the dry season there's only about 30 metres of water and the Vietcong could practically put their bazookas through the portholes. We made £20 or £30 million out of the business, but we never knew why until afterwards.

'The key to the business is to charge a premium that's just at the level of pain, and keep 'em coming. Keep 'em coming.'

`Keeping them coming' was one of the things that made Posgate unpopular. He took on business at a furious pace, brokers lining up at his box in 'the room' for a sharp and unpredictable interview which paid no regard to established pecking orders slips (the forms on which underwrit- ers stamp their commitments) flying around him like confetti.

The capacity of his syndicates grew from £120,000 (of premium income) in 1962 to £250 million at his peak. Disciplined for accounting irregularities in 1970, he was in hot water a few years later for taking on more business than he had capacity to underwrite. Throughout his career, the Lloyd's establishment pressed him to share the cream of the business around.

'They were always hauling me up to the Committee room. After a while I learned that if there was tea on the table, they were going to be kind to me. If there weren't any teacups, I was in for a rocket.

'Once, in about 1980, they called a meet- ing of underwriters and said that war busi- ness had to be spread across the market, there was £65 million of premiums to be spread around for everyone. I checked the figures in my notebook, and my syndicates were already writing £70 million.

`But in business I believe in dog-eat-dog, survival of the fittest, not protection of the weakest. I regarded every other syndicate as a rival. The powers-that-be said that good business should subsidise bad across the market. But I wanted 100 per cent good business. I cut rates to get it. They wanted it to be a club, a lot of them are masons, but I'm not a clubable fellow, never belonged to a club in my life. Clubs won't have me, they don't think I'm a proper person. I'm anti-cartels and, being a Catholic, I'm anti-freemasonry.'

For six years in the 1970s, the Commit- tee would not allow Posgate to be an underwriting agent. Instead they put him under the wing of Kenneth Grob, 'the Grobfather', chairman of a substantial Lloyd's firm, Alexander Howden, but an altogether less engaging figure.

Eventually Posgate's success and market influence brought him a form of respectability. By 1981, the establishment simply could not afford to cold-shoulder him; he became a member of the Lloyd's Committee itself. At that stage, he says, `they wanted to imitate me. I had 15 imita- tors in the market.'

But 1981 was also the year in which Howden (of which Posgate had become a director) was acquired by the American insurance giant Alexander & Alexander. The process of due diligence revealed a can of worms; millions were alleged to have gone missing. Posgate was accused by a Lloyd's disciplinary committee, but found not guilty, of misappropriating funds and falsifying accounts. He was found guilty of lesser charges, including accepting a Pissarro painting (which he described as `not that good, not that expensive') as a bribe.

The Committee recommended that Pos- gate be banned from underwriting for life. He embarked on a relentless campaign to clear himself. In 1985, an appeals tribunal commuted the sentence to a six-month suspension. He sought to return to work the following year, only to find that the Lloyd's Committee, increasingly anxious to be seen to eradicate all taint of scandal, had declared him not 'fit and proper'. He appealed again, but no grounds were found on which to overturn the second decision.

Then, more than five years after the `Howden Affair', came criminal charges of conspiracy and fraud against Posgate, Grob and others. The trial took two more years to prepare, lasted three months, cost £2 million, and ended in acquittal on all charges. Posgate (who maintained both his good humour and his box at Goodwood throughout the case) declared himself vin- dicated, but made no further attempts to re-enter Lloyd's as an underwriter. 'It's such an uninteresting place nowadays,' he said. 'Anyway, I don't think they'd have me back.'

He fought one last battle, however, at considerable expense, to be allowed to remain as a name on syndicates run by other underwriters, selected with his usual shrewdness — but subsequently suffered some £500,000 of underwriting losses. Does that mean that the style of business he initiated has not stood the test of time? No, he says, the mistake has been to let the good business be diffused across the market; in his day, he kept the good busi- ness in one place.

There is a hint, if not of remorse, of nos- talgia mixed with frustration. He may not be clubable, but being in the thick of the play is always more fun than sitting on the sidelines commentating. A clever, red- blooded maverick, he paid a heavy price for relatively minor indiscretions and a bad attitude. The heaviest price is to be left out of the action. So does he regret the past ten years? 'Regret? What I regret is that I failed to bring Lloyd's into the 21st century. The institution is good, it's the people that are lousy.'

Previous page

Previous page