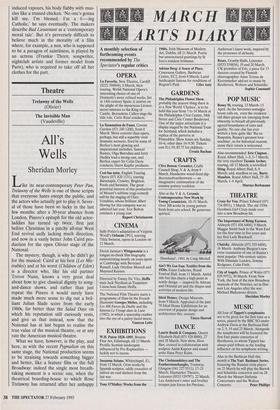

Theatre

Trelawny of the Wells (Olivier) The Invisible Man (Vaudeville)

All's Wells

Sheridan Morley

Like its near-contemporary Peter Pan, Trelawny of the Wells is one of those scripts that everyone hates except the public, and the actors who actually get to play it. Sever- al of those have been so lucky in the last few months: after a 30-year absence from London, Pinero's epitaph for the old actor- laddies has turned up twice, first just before Christmas in a patchy all-star West End revival sadly lacking much direction, and now in a vastly better John Caird pro- duction for the open Olivier stage of the National.

The mystery, though, is why he didn't go for the musical: Caird at his best (Les Mis- erables) and at his worst (Children of Eden) is a director who, like his old partner Trevor Nunn, knows a very great deal about how to give classical dignity to song- and-dance shows, and rather than just repeat the Pinero it would surely have made much more sense to dig out a bril- liant Julian Slade score from the early 1960s, far better than the Salad Days on which his reputation still curiously rests, and give us that instead, now that the National has at last begun to realise the true value of the musical theatre, or at any rate the American musical theatre.

What we have, however, is the play, and here, as with the recent Pygmalion on this same stage, the National production seems to be straining towards something bigger and better, like a feature film or the full Broadway: indeed the single most breath- taking moment is a scenic one, when the theatrical boarding-house to which Rose Trelawny has returned after her unhappy sojourn in Cavendish Square is suddenly opened out to reveal the bare stage of a huge Victorian playhouse complete with wings and royal boxes.

But the problem with the play is still the problem with Pinero; as Tynan was later to say of Rattigan, he was geographically pos- sessed by the old guard while temperamen- tally inclined towards the rebels, and as a result Trelawny as character and drama is in severe danger of a broken neck from try- ing to face in both directions at once.

Written in the 1890s but set back 30 years, the play mourns the passing of the old barnstormers (superlatively played here by Betty Marsden and Michael Bryant: 'I am required to play an old, ham actor.' `Oh, but dearest, will you be able to come close to it?') while celebrating the arrival of Tom Robertson (thinly disguised here as Tom Wrench) and his 'cup and saucer real- ism'. Yet by the time the play was first seen, that too was being thrown out of the green-room by the arrival of Bernard Shaw and even Ibsen, so Pinero is left with a kind of Garrick Club nostalgia trip on to which he has had to batch a conventional love story in the hope of binding it all together without having his audience reel out under an attack of greasepaint fumes.

Everything therefore depends on the playing, and here Caird is superbly served: Helen McCrory, in the title role, perfectly captures Rose's crossover from lovelorn ingenue to wounded woman, while Steven Pacey, Kevin Williams and Adam Kotz bril- liantly distinguish between the various clas- sic theatrical types who surround her in the boarding-house and backstage.

But the performance of the evening, indeed I suspect already one of the award- winning performances of the year, is that of Robin Bailey as Vice Chancellor Sir William Gower. From his first appearance from beneath a handkerchief in the awful stillness of Cavendish Square, through his horror at the social ineptitude of the play- ers (`Have we no chairs? Do we lack chairs?'), to his heartbreaking conversion at Rose's hands to his own theatrical mem- ories ('Kean? Ah, Kean: he was a splendid gypsy'), Bailey and Caird have wonderfully recognised that this is essentially a play about Gower and his reawakening to the magic of theatre as much as it is ever about Rose's marital problems or Tom's desire to be a playwright. Trelawny of the Wells is that curious contradiction, a great play without being a very good one; but for the second time in 30 years the National has shown us precisely how it should be done.

At the Vaudeville from Stratford East, The Invisible Man is Ken Hill's joyous box of conjuring tricks: the old H.G. Wells sci- fi thriller turned a century later into a series of stagey conjuring tricks, through which wanders Brian Murphy as an ami- able master of eccentric ceremonies: to cel- ebrate the 40th birthday of Joan Littlewood's Stratford East, nothing could be better or more music-hall familiar.

Previous page

Previous page