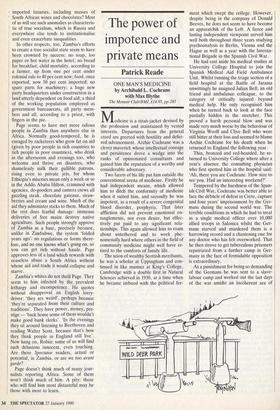

The power of impotence and private means

Patrick Reade

ONE MAN'S MEDICINE by Archibald L. Cochrane with Max Blythe

The Memoir ClubIBMJ, £14.95, pp.283

Medicine is a strait-jacket devised by the profession and maintained by vested interests. Departures from the general creed are greeted with hostility and defer- red advancement. Archie Cochrane was a clever maverick whose intellectual courage and persistence drove a wedge into the ranks of opinionated consultants and gained him the reputation of a worthy and considerable adversary.

Two facets of his life put him outside the conventional arena of medicine. Firstly he had independent means, which allowed him to ditch the conformity of medicine when it suited him, and secondly he was impotent, as a result of a severe congenital blood disorder, porphyria. That later affliction did not prevent emotional en- tanglements, nor even desire, but effec- tively put paid to any significant rela- tionships, This again allowed him to roam about untethered and to work phe- nomenally hard where others in the field of community medicine might well have re- tired to the comforts of family life.

The scion of wealthy Scottish merchants, he was a scholar at Uppingham and con- tinued in like manner at King's College, Cambridge with a double first in Natural Sciences achieved in 1930, at a time when he became imbued with the political fer-

ment which swept the college. However, despite being in the company of Donald Beeves, he does not seem to have become an apparatchik of the Left. A fierce and lasting independent viewpoint served him well both throughout three years studying psychoanalysis in Berlin, Vienna and the Hague as well as a year with the Interna- tional Brigade in the Spanish Civil War.

He had cast aside his medical studies at University College Hospital to join the Spanish Medical Aid Field Ambulance Unit. Whilst running the triage section of a field hospital at the Battle of Jarama unwittingly he assigned Julian Bell, an old friend and ambulance colleague, to the category of critically injured beyond medical help. He only recognised him when he turned back to look at the face partially hidden in the stretcher. This proved a harsh personal blow and was made very much worse by the behaviour of Virginia Woolf and Clive Bell who were still bitter at their loss and seemed to blame Archie Cochrane for his death when he returned to England the following year.

Thin, bronzed and red-bearded, he re- turned to University College where after a year's absence the consulting physician who first spotted him in the hospital said: 'Ah, there you are Cochrane. How nice to see you. Had an interesting weekend?'

Tempered by the harshness of the Span- ish Civil War, Cochrane was better able to face the debacle of defeat in Crete, capture and four years' imprisonment by the Ger- mans during the second world war. The terrible conditions in which he had to treat as a single medical officer over 10,000 allied troops in Salonica whilst the Ger- mans starved and murdered them is a harrowing record and a chastening one for any doctor who has felt overworked. That he then strove to get tuberculous prisoners repatriated from a further camp in Ger- many in the face' of formidable opposition is extraordinary.

As a punishment for being so demanding of the Germans he was sent to a slave- labour camp and worked out the last days of the war amidst an incoherent sea of international captives threatened daily by the real fear of the invading Russians. From the comforts of the late-20th century it is impossible to consider the brutalities which he faced and the resources he found to meet them. For those ghastly years he was awarded the MBE, a paltry recogni- tion for medical services to prisoners..

Following the war, he devoted himself to the study of TB and community medicine in the Rhondda Valley where for almost 30 years he sought to elucidate patterns of disorder and mortality from the coal- miners' disease pneumoconiosis and a host of other conditions including anaemia and glaucoma. He was made TB professor at the Welsh National Medical School and then Director of the Medical Research Council Epidemiology Unit in Cardiff. Here he was one of the first to question the value of coronary care units and propose a trial of their effectiveness in • terms of patient survival. He developed and did a great deal to publicise the idea of random trials of many drugs and clinical proce- dures. He sought to make clinicians re- evaluate what they were actually doing for the patients.

These memoirs give vivid colour to the events in Spain and Europe during the war; they also present a graphic and dynamic picture of the changes in medicine during the last 50 years. The disappointments lie in the characterisations of the household names which he is always ready to drop. It is a vacuous exercise to record meetings with great literary and academic figures unless we learn something about them. Thus on a social visit (sic) to Madrid during the Civil War he recounts: 'I met Ernest Hemingway who seemed an alcoholic bore.' That view may be tenable but the supporting evidence is not provided.

Again he writes 'I am told I met Blunt,' and was told that I had shaken hands with Tito', but this is not informative. The same fault occurs when he describes life in Cambridge: 'I met some of the younger established scientists like C. P. Snow.' One expects something more but nothing comes. George Orwell in Spain and Evelyn Waugh in Crete barely get a paragraph each and yet their presence had consider-

able literary results in Homage to Catalonia and Unconditional Surrender, as indeed did Hemingway's in For Whom the Bell Tolls. Cochrane does not really understand

People and therefore fails to show any emotional empathy although he was able to ameliorate the physical sufferings of many thousands throughout his lifetime. It Is perhaps because he was unable to develop a full relationship with any indi- vidual that he became blind in some respects to the uniqueness in every person.

Previous page

Previous page