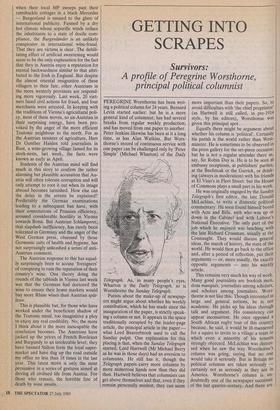

GETTING INTO SCRAPES

Survivors: A profile of Peregrine Worstho me, principal political columnist

PEREGRINE Worsthorne has been writ- ing a political column for 24 years. Bernard Levin started earlier: but he is a more general kind of columnist; has had several breaks from regular weekly production; and has moved from one paper to another. Peter Jenkins likewise has been at it a long time, as has Alan Watkins. But Wors- thome's record of continuous service with one paper can be challenged only by 'Peter Simple' (Michael Wharton) of the Daily Telegraph. As, in many people's eyes, Wharton is the Daily Telegraph, so is Worsthorne the Sunday Telegraph.

Purists about the make-up of newspap- ers might argue about whether his weekly contribution, which he has made since the inauguration of the paper, is strictly speak- ing a column or not. It appears in the space traditionally occupied by the leader-page article, the principal article in the paper — what Lord Beaverbrook used to call the Sunday pulpit. One explanation for this placing is that, when the Sunday Telegraph started, Lord Hartwell (Mr Michael Berry as he was in those days) had an aversion to columnists. He still has it, though the Telegraph papers carry more columns by more numerous hands now than they did then. Hartwell believes that columnists can get above themselves and that, even if they remain personally modest, they can seem more important than their papers. So, to avoid difficulties with 'the chief proprietor' (as Hartwell is still called, in pre-1914 style, by his editors), Worsthorne was given this principal spot.

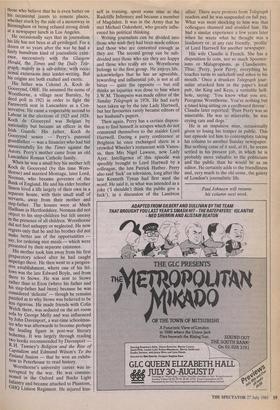

Equally there might be argument about whether his column is 'political'. Certainly his parish is the world rather than West- minster. He is sometimes to be observed in the press gallery for the set-piece occasion; but he is not a regular attender there as, say, Sir Robin Day is. He is to be seen at embassy receptions, at publishers' parties, at the Beefsteak or the Garrick, or drink- ing (always in moderation) with his friends at El Vino's in Fleet Street: but the House of Commons plays a small part in his work.

He was originally engaged by the Sunday Telegraph's first editor, the late Donald McLachlan, to write a domestic political commentary. He soon found himself bored with Acts and Bills, with who was up or down in the Cabinet and with Labour's National Executive. The only part of the job which he enjoyed was lunching with the late Richard Crossman, usually at the Connaught. They would discuss general ideas, the march of history, the state of the world. He would then go back to the office and, after a period of reflection, put their arguments — or, more usually, the exactly opposite arguments — into his weekly article.

This remains very much his way of work. Many good journalists are bookish men, dons manques, journalists among scholars, and scholars among journalists. Wors- thorne is not like this. Though interested in large and general notions, he is not academic. He picks up his ideas through talk and argument. His consistency can appear inconsistent. He once opposed a South African rugby tour of this country because, he said, it would be ill-mannered for a squire to invite to a village a team to which even a minority of his tenants strongly objected. McLachlan was distres- sed when he saw the way Worsthorne's column was going, saying that no one would take it seriously. But in Britain no political columns are taken seriously — certainly not as seriously as they are in America. Worsthorne's column is un- doubtedly one of the newspaper successes of the last quarter-century. And there are those who believe that he is even better on his occasional jaunts to remote places, Whether stuck by the side of a motorway in Birmingham or being refused strong drink at a newspaper lunch in Los Angeles. He occasionally says that in journalism his life has not been at all privileged. For a dozen or so years after the war he had a fairly humdrum kind of journalistic exist- ence, successively with the Glasgow Herald, the Times and the Daily Tele- graph, mainly as a sub-editor, with occa- sional excursions into leader-writing. But his origins are both exalted and exotic.

His father was Colonel A. Koch de Gooreynd, OBE. He assumed the name of Worsthorne, a village near Burnley, by deed poll in 1921 in order to fight the Farnworth seat in Lancashire as a Con- servative. He came a respectable second to Labour in the elections of 1923 and 1924. Koch de Gooreynd was Belgian by nationality but became an officer in the Irish Guards. His father, Koch de Gooreynd senior — Peffy's paternal grandfather — was a financier who had bid unsuccessfully for the Times against the Astors. Perry's mother came from an old Lancashire Roman Catholic family. When he was a small boy his mother left Koch de Gooreynd (by this time Wors- thorne) and married Montagu, later Lord, Norman, who became governor of the Bank of England. He and his elder brother Simon lied a life largely of their own in a separate house, with their small staff of servants, away from their mother and step-father. The houses were at Much Hadham in Hertfordshire. Norman did not °. hlect to his step-children but felt uneasy in the presence of all children. Worsthorne did not feel unhappy or neglected. He now regrets only that he and his brother did not make better use of the opportunities — say, for ordering nice meals — which were presented by their separate existence. His mother took him away from his first Preparatory school after he had caught linpetigo there. He then went to a progres- sive establishment, where one of his fel- lows was the late Edward Boyle, and from there to Stowe. He was sent to Stowe rather than to Eton (where his father and his step-father had been) because he was considered 'delicate' — though he remains Puzzled as to why Stowe was believed to be less rigorous. He made friends with Cohn Welch there, was seduced on the art room sofa by George Melly and was influenced by John Davenport, a war-time schoolmas- ter who was afterwards to become perhaps the leading figure in post-war literary bohemia. It was largely through reading two books recommended by Davenport Tawney's Religion and the Rise of Capitalism and Edmund Wilson's To the Finland Station — that he won an exhibi- tion to Peterhouse to read history. Worsthorne's university career was in- terrupted by the war. He was commis- sioned in the Oxford and Bucks Light Infantry and became attached to Phantom, GHQ Liaison Regiment. He injured him- self in training, spent some time at the Radcliffe Infirmary and became a member of Magdalen. It was in the Army that he met Michael Oakeshott, who greatly influ- enced his political thinking.

Writing journalists can be divided into those who wish they had been made editors and those who are contented enough as they are. The second group can be sub- divided into those who say they are happy and those who really are so. Worsthorne belongs to the first group. He enjoys life, acknowledges that he has an agreeable, rewarding and influential job, is not at all bitter — quite the opposite — but still thinks an injustice was done to him when J.W.M. Thompson was made editor of the Sunday Telegraph in 1976. He had early been taken up by the late Lady Hartwell, but her favourites rarely became editors of her husband's papers.

Then again, Perry has a certain disposi- tion to find himself in scrapes which do not commend themselves to the staider Lord Hartwell. During a party conference at Brighton he once exchanged shirts in a crowded Wheeler's restaurant with Vanes- sa, then Mrs Nigel Lawson, now Lady Ayer. Intelligence of this episode was speedily brought to Lord Hartwell by a colleague, the late Patrick Hutber. Perry also said 'fuck' on television, long after the late Kenneth Tynan had first used the word. He said it, in what was intended as a joke CI shouldn't think the public give a fuck'), in a discussion of the Lambton affair. There were protests from Telegraph readers and he was suspended on full pay. What was most shocking to him was that colleagues shunned and avoided him. He had a similar experience a few years later when he wrote what he thought was a laudatory or, at any rate friendly, 'profile' of Lord Hartwell for another newspaper.

His wife Claudie is French. She has a disposition to coin, not so much Spooner- isms or Malapropisms, as Claudieisms. Thus: 'Perry, poor Perry, everything he touches turns to sackcloth and ashes in his mouth.' Once a drunken Telegraph jour- nalist attacked him in the paper's local pub, the King and Keys, a veritable hell- hole, saying: 'You know what you are, Peregrine Worsthorne. You're nothing but a tinsel king sitting on a cardboard throne'. Claudie later reported: 'Poor Perry was so miserable. He was so miserable, he was crying cats and dogs.'

He is an impulsive man, occasionally given to losing his temper in public. This last episode led him to contemplate taking his column to another Sunday newspaper. But nothing came of it and, at 61, he seems settled in his present job, in which he is probably more valuable to the politicians and the public than he would be as an editor. He certainly adds to the friendliness and, very much in the old sense, the gaiety of London's journalistic life.

Previous page

Previous page